On September 26th, students from the rural teacher training college of Ayotzinapa traveled to Iguala – 120 miles south of Mexico City. The students needed to raise money for a trip to Mexico City, and consequentially asked drivers from Iguala for donations to fund their trip to the capital. While the students’ buses drove through Iguala, local police shot at them, killed three, and abducted 43, all of whom are now missing.

What happened in Iguala is a macabre irony that reminds us how little has changed in Mexico in almost half a century.

In Mexico, students have long had a contentious relationship with the police and military. Before the abductions, the group planned to use the funds they raised on September 26th to join other students in Mexico City for an annual demonstration commemorating the Tlatelolco massacre – one of darkest episodes in Mexico’s recent history. On October 2,1968 – 10 days before the start of the Summer Olympics in Mexico City – police and military shot at students as they were peacefully demanding democracy. Today, no one knows exactly how many students died (estimates range between 30 and 300).

September’s events in Iguala bear resemblance to this somber chapter in Mexican history.

The September 26th incident in Iguala happened in the blink of an eye. Many of the 43 missing students were last seen being bundled in police cars. These students are young – between 18 and 20 years old – and after 20 days of investigation, no one knows where they are. No one has been charged or pled guilty. In contrast to other documented human rights violations in the world, the international community has been lukewarm in its response to these horrendous events. The U.S. needs to be strategic in its foreign policy objectives and start paying more attention south of the Rio Grande.

President Peña Nieto came to power in 2012 and, found his country immersed in war. Drug mafias waged war in many Mexican communities. The 2012 presidential election was a referendum on President Calderon’s term, and Mexicans spoke clearly at the polls. The on-going violence relegated the ruling conservative party to a distant third.. Mexicans wanted an end to the bloodshed that had taken over the country. Consequentially, President Peña launched a public relations campaign in Mexico and abroad that rested on a simple premise: don´t speak about the violence, let everyone ignore what is happening, and sell an image of Mexico as a reforming country moving forward.

It worked, for a while.

Since coming to office, President Peña and his political party have changed the political arena in Mexico. They struck deals with opposition parties with spectacular results: three constitutional amendments and many new laws in less than two years. These normative changes occurred in a range of areas from telecommunications and energy to education and public finance. President Peña framed these reforms as much needed changes to move the country forward. The fast pace of reforms had authorities like Christine Lagarde, International Monetary Fund Director, claiming that Mexico could become an inspiration for the rest of the world.

Time magazine dedicated one of its covers to President Peña photographing him as a Hollywood superhero with the headline ¨Saving Mexico.¨ The press all over the world bought the President’s efforts to portray Mexico as a country moving forward. Pundits claimed that the U.S. political system had something to learn from the Mexican reform program. The mirage is over.

The events in Iguala highlight the weaknesses at all levels of Mexican government. Drugs continue to taint the service of public officials. Last year, the second highest authority in the country – the Ministry of the Interior – and the Federal Prosecutor, both knew of allegations that Iguala´s mayor had clear links with drug lords and killed a member of his political party. It appears that no one bothered to investigate. The governor of Guerrero, amid growing criticism, recently acknowledged that Iguala´s police are infiltrated by the drug cartels.

What is most striking is America’s silence with respect to these events. Consider President Obama´s unambiguous response to the clashes between Venezuelan police and students earlier this year. He then said: ¨The [Venezuelan] government ought to focus on addressing the legitimate grievances of the Venezuelan people.¨

Today, high-ranking US officials have not voiced concerns over the deteriorating events in Mexico since September 26th. The US response to human rights violations around the globe – including the recent events in Iguala – should be unambiguous and consistent. Silence is tantamount to complicity.

International media has likewise paid little attention to the events. The story only made it to the front cover of The New York Times on October 7th – 11 days after the students disappeared. Mexicans have taken to the streets in seven countries and more than 60 cities worldwide – including six cities in the US on October 15th. The international community needs to look more closely at the unraveling events in Mexico, demand a transparent investigation, and, most important of all, make sure those 43 missing students go back to their families alive. As Mexicans all over the world are demanding: “They took them alive, we want them back alive.”

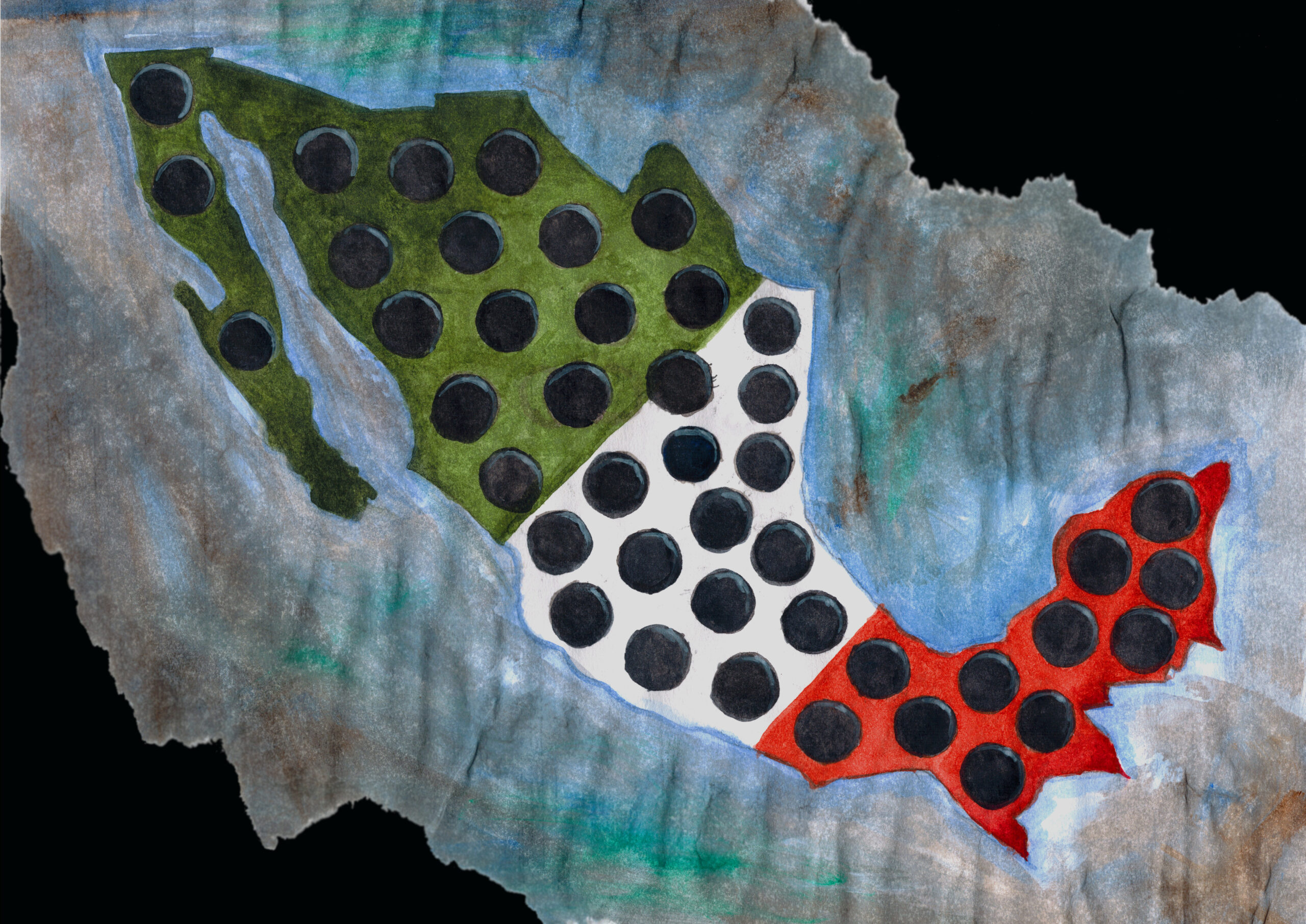

Illustration by Zak Ostertag.