Photograph of Anna May Wong

This piece was published in the 32nd print volume of the Asian American Policy Review.

There is a danger of a single story becoming the only story, and it is important to see counter-narratives as well. More stories need to show the breadth, depth, and nuance of our multi-ethnic, varied communities and more representation for those under the API umbrella that are typically less represented.

In 2020, anti-Asian hate incidents spiked 149 percent across the larger cities in America, even though the overall hate incident numbers declined.1 Moreover, Stop AAPI Hate’s National Report logged over ten thousand anti-Asian incidents from 19 March 2020 to 30 September 2021, of which 44.4 percent occurred in 2020 and 55.7 percent occurred in 2021.2

Although media attention about the violent attacks against Asians in America has waned since the global spotlight ignited by the Atlanta shootings in March 2021 and the various “Stop Asian/AAPI Hate” campaigns and hashtags, such violent acts remain rampant across the country.

In October 2021 in Los Angeles, Olympic gold medalist gymnast Sunisa Lee said she was pepper-sprayed during a racist attack by people in a passing car shouting racial slurs and telling her and her friends to “go back where they came from.”3

Violence against Asians in America is not new. Nor is the intersectionality of law, politics, and media in affecting our lives. Our communities have suffered from racist laws and policies dating back to our earliest arrivals centuries ago and continue today. In order to build a better world, we must acknowledge the role the media plays in shaping our culture and harness its power to create change.

Why Media Matters

Media creates the narrative foundation for how people of color are perceived and treated in the real world. Negative portrayals have profound and insidious consequences, which is why this is not just a representation issue but also a social justice issue. Stereotypical portrayals of Asian American characters flood our screens again and again. These repeated reminders of dehumanizing stereotypes make it psychologically easier to hurt that group of people.4 Neuroscience research conducted by Susan Fiske, a psychologist at Princeton University and a leading expert on prejudice, found that dehumanizing others activated the brain’s disgust regions and deactivated the empathy regions.5 There is a reason this was a common tactic of wartime propaganda. When people see Asian Americans as being “foreign,” it creates an “in-group/out-group” mentality, making it easier to treat Asians in America with hostility and to engage in acts of violence and discrimination against them.

As noted in a 2021 USC Annenberg study analyzing seventy-nine primary and secondary Asian and Pacific Islander (“API”) characters from the most popular films of 2019, roughly 25 percent of the characters died by the end of the film, with all but one death ending violently.6 In 1959, the legendary actress Anna May Wong famously lamented “when I die, my epitaph should be: ‘I died a thousand deaths,’” referring to the tragic fate of many of the Asian characters she played in her film career. This devaluation of human life translates directly to the way Asians in America are treated in real life.

What we watch on our screens impacts the way we think, feel, and act. According to the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, “eighty percent of media consumed worldwide is made in the United States.”7 Thus, Hollywood has a profound responsibility to acknowledge its global influence on how cultures and communities are portrayed and perceived. That influence has only grown during the COVID-19 pandemic as viewership of content exploded, largely on streaming services. Nielsen reports that total streaming minutes increased from 117.7 billion in December 2019 to 132 billion in December 2020.8

What happens, then, when viewers are overexposed to White-centric narratives that marginalize—or worse, erase and demean—the experiences and narratives of other communities? In 1976, researchers George Gerbner and Larry Gross coined the phrase “symbolic annihilation” to describe the effects of being erased in the media.9 They posited that “representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation.”10 In other words, if people don’t see themselves or those like them reflected in the fictional media they consume, they are deemed insignificant or unimportant in the real world.

Why Stereotypes Are So Harmful

Stereotypes of Asians in America have persisted throughout history, largely propagated by the media. Tropes such as the model minority and perpetual foreigner have led to real world harm against these communities, including in corporate America. According to the Harvard Business Review, Asians are the most likely to be hired, but the least likely to be promoted.11 Moreover, tropes, such as hypersexualization of Asian women and emasculation of Asian men, also have detrimental real-world consequences. What follows is a high-level discussion of these four tropes and their social implications.

1. Model Minority Myth

The term “model minority” was coined by a White sociologist William Petersen and first published in a 1966 New York Times Magazine article, “Success story: Japanese American style.”12 This misleading label presents Asian Americans as studious, educated, successful, smart, and hardworking. It has been translated to the screen as the overachieving Asian person, the nerdy sidekick, the IT person, the math whiz, and other manifestations. While on the surface these may seem like positive attributes, the model minority myth is simply a myth developed in the post-war era to create a racial wedge and minimize the role systemic racism plays in the persistent struggles of other racial and ethnic minority groups, especially Black Americans during the rise of the Civil Rights Movement.13 It conveyed the message “if Asians can do it, why can’t you?”

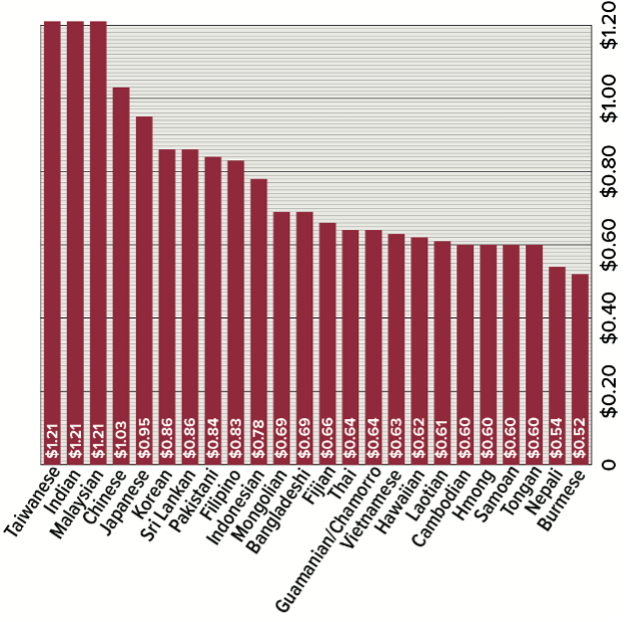

Furthermore, the model minority myth generally focuses on East Asians or South Asians, masking the needs of different ethnic communities under the larger Asian American umbrella and erasing them from the conversations around poverty and wage disparities. Contrary to this belief, a 2018 Pew Research Center report found that Asian Americans, in fact, have the largest wage gap of any racial group.14 The 90/10 ratio is commonly used to measure the income gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 10 percent ends of the earnings spectrum. In 2016, the 90/10 ratio for Asians was 10.7, meaning those in the 90th percentile had 10.7 times the income of Asians at the 10th percentile, which is higher than any other communities studied.15 Moreover, the wage gap for Asians has increased 77 percent from 1970 to 2016.16 Reflected in Figure 1, disaggregated data highlighting this income disparity disputes the notion that all Asians are economically successful and do not need social policies or assistance.

9 March 2021 was #AAPIEqualPayDay, marking the day that AAPI women have to work into 2021 to earn the same amount of money that non-Hispanic White men earned in 2020.17 On average, AAPI women earn eighty-five cents for every dollar earned by White men, but when broken down into sub-ethnic groups (see Figure 1), a very different picture emerges.

Taiwanese and Indian women over-index at $1.21 to every dollar earned by a White man. However, on the other end of the spectrum, Burmese women are at the bottom, earning fifty-two cents to every dollar earned by a White man, making them one of the lowest paid people in the nation.18 Moreover, according to 2017 Census data, Filipino Americans faced a 6 percent poverty rate, compared to the 16.2 percent for Hmong Americans.19 The model minority myth is extremely detrimental to policy arguments for economic support for Asian communities at the lower end of the earnings spectrum.

A related issue with the model minority myth is the misguided belief that Asians in America do not face discrimination or racism, a notion easily rejected based on the discussion contained herein.20 The Harvard Business Review’s findings that Asians are the least likely to be promoted reflects the implicit bias stemming from the model minority myth. Asians are seen as hard-working and smart worker-bees, but not as charismatic and effective leaders.21

2. Perpetual Foreigner

As demonstrated in the story recounted by Sunisa Lee who was told to “go back to where [she] came from,” another stereotype that leads to real-world harm against Asians in America is the perpetual foreigner trope. Asians are often depicted on-screen as foreign, exotic, and inherently un-American. These characters are portrayed with exaggerated foreign accents, an inability to understand English, a reverence for non-Christian religious practices, and an adherence to outdated and “barbaric” practices such as eating cats or dogs. To be clear, there is nothing wrong or offensive about being an immigrant or having an accent. But in these stereotypical portrayals, the “other-ness” becomes the butt of the jokes and Asians are mocked, denigrated, and singled out for being the “other.” A few tropes flow from the perpetual foreigner concept, including:

A. “Yellow Peril”

In the 1850s, Asian immigrants began arriving in significant numbers to the US West Coast and were quickly exploited as a cheap labor force by White American industrialists.22 This fear of economic competition and xenophobia from White Americans led to a rise of racist, anti-Asian sentiment, which was often further capitalized upon for political gain, such as the Workingmen’s Party of California adoption of “The Chinese Must Go” as their official party slogan.23 Art often mirrors life, and we find the existence of “Yellow Peril” images since the early days of film and television painting primarily East Asians and Southeast Asians as a sneaky, villainous, and foreign threat to Western values and life. Yellow Peril was so ingrained in the cultural consciousness that it was coded into children’s movies like Lady and the Tramp (1955), which included two sinister Siamese cats Si and Am performing the racist “Siamese Cat Song.” Additionally, the target ethnicity often shifts and changes in relation to current US political relationships. For example, in 1915’s The Cheat, the villain was originally of Japanese descent. As relations with Japan warmed, the film’s villain was changed to Burmese in the 1918 re-release.24

B. “Brown Peril” / Islamophobia

The South Asian equivalent is “Brown Peril,” and it has been present for as long as its East Asian counterpart. Portrayals escalated considerably in the wake of 9/11 and with “the war on terror” continuously streaming for two decades since. Islamophobia has taken up the mantle where Yellow Peril once stood. Interchangeable brown faces are seen as the face of terrorism, with various South Asian, Middle Eastern and North African ethnicities being conflated with one another.

While no longer as explicit as Fu Manchu stroking his beard, Yellow and Brown Peril still exist in modern film and television in the form of nameless Yakuza, ninjas, triads, tongs, Communist invaders, terrorist plotlines, and the seemingly ubiquitous Chinatown episode in every procedural series. In many of these narratives, the Asian characters are nameless, faceless, and storyless. They tend to have no lines, are given no motivation, and follow commands mindlessly, closely resembling props instead of characters. They are subjected to racial slurs and, more often than not, killed violently.

C. Dragon Lady / Mata Hari

When this foreign peril is placed upon an Asian woman, the trope of the Dragon Lady or the Mata Hari is born. This portrayal is still nefarious and untrustworthy, but with an additional layer of sexual availability and immorality.25 The Dragon Lady trope stems from the early, racist belief that all Chinese women immigrating to the United States were prostitutes and had the 45 potential to spread foreign disease via sex work.26 This belief was so pervasive, it led to the passing of the Page Act, which effectively banned the immigration of East Asian women and is considered the first federal law restricting immigration and the precursor to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.27

“Mata Hari” has become a cultural shorthand for a lethal double agent who uses her powers of seduction to extract secrets from her many lovers. In real life, Mata Hari was the stage name of a Dutch sex worker who falsely claimed Indonesian heritage. Capitalizing on society’s fascination with the Orient and the sexual objectification of Asian women, she exploited the trope of the hyper-sexualized Asian woman. She was accused and eventually executed for espionage.28

D. China Doll / Lotus Blossom / Geisha Girl

In direct opposition to the Dragon Lady/Mata Hari trope, the China Doll/ Lotus Blossom/Geisha Girl presents Asian women as meek and submissive, often in sexualized contexts, needing to be saved and willing to make tremendous sacrifices for her master. This trope is rooted in Giacomo Puccini’s popular opera Madama Butterfly, which was adapted into at least five feature films by 1932 and continues to live in mainstream consciousness due to the popularity of the musical Miss Saigon.

3. Hypersexualization of Asian Women

The hypersexualization of Asian women is one clear example of how images in film and television have real-life consequences.29 The phrase “me so horny; me love you long time” from Full Metal Jacket, a 1987 film by Stanley Kubrick, is still used to taunt Asian women today. It is also sampled in 2 Live Crew’s “Me So Horny”, which stayed on the Billboard Top 100 for thirty weeks in 1989.30

Unfortunately, the past thirty years has not shown much improvement. Asian women continue to be hypersexualized on screen. In a recent study of 1,300 most popular films from 2007 to 2019, nearly twenty-five percent of API women were clad in provocative attire and twenty percent of API women were portrayed with some type of nudity.31 Additionally, a 2021 CAPE research study with the Geena Davis Institute found that “female Asian and Pacific Islander characters are more likely than female characters of any other race to be objectified on screen.”32

These demeaning portrayals lead to devaluing the lives and agency of Asian women. For example, an official said the Atlanta spa shooter had a “very bad day” and accepted his sexual addiction defense.33 Of the over ten thousand anti-Asian hate incidents reported to Stop AAPI Hate from 19 March 2020 to 30 September 2021, 62 percent were against women.34

4. Emasculation of Asian Men

While Asian women are over-sexualized and fetishized, Asian men are often emasculated and humiliated. Dating back to the 1850s and the initial wave of Asian immigration, Asian men were historically limited to domestic work traditionally done by women such as nannying, cooking, and laundry.35 Emasculation of Asian men was also a consistent tactic of war propaganda.

It is important to recognize that the perception of Asian men as unattractive and sexually undesirable was manufactured by the media. Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa was the first Hollywood sex symbol in the early days of the entertainment industry.36 His popularity with White women sparked public fear that led to the reinforcement of policies against showing interracial relationships on screen, such as the Motion Picture Production Code or the Hays Code, a set of regulations on moral content in films that Hollywood imposed on itself to preempt outside censorship.37

Although depictions of Asian men have been gradually changing, an analysis of the top-grossing films of 2019 revealed that 58 percent of API male characters had no romantic relationship compared to 37.5 percent of API female characters. In Escape Room, a South Asian male character is told, “Stop being chivalrous, no one wants to have sex with you.”38

What Are the Potential Solutions

The good news is that media representation continues to evolve. Streaming platforms and social media have changed the game. Audiences are savvier and critical feedback is almost instantaneous. Here are some narrative and structural suggestions for continued forward movement.

1. Stories By Us, for Everyone

Changing the narrative can change the world. Start with who is telling the story. Writers are important because representation starts on the page. We need stories by us for everyone that tell universal narratives through specific lenses.

We need more stories, in any format or genre, centering API characters and experiences rather than merely making them the sidekick or underdeveloped love interest. This must be done thoughtfully, though, with an eye toward seeding new stories and steering away from stories that may be over-represented.39 For example, not all Vietnamese stories need to be about the Vietnam War or the trauma of being a refugee. South Asian storylines do not always have to revolve around arranged marriage. In light of the economic disparity in the API communities rejecting the model minority myth, there should be more than the crazy rich Asian storyline.

That is not to say these stories are invalid or even inherently inauthentic. However, there is a danger of a single story becoming the only story, and it is important to see counter-narratives as well. More stories need to show the breadth, depth, and nuance of our multi-ethnic, varied communities and more representation for those under the API umbrella that are typically less represented.

Who gets to be the hero? Whose story are we telling? Is there a way to tell this story in a way that does not center around a White male protagonist?

2. More Intersectional Stories

As racial demographics continue to shift America toward becoming majority-minority and identity conversations continue to evolve, Hollywood must catch up with more intersectional narratives.

For example, a 2021 USC Annenberg study states that “the lack of API characters overall extends to intersectional communities . . . Only 15 API characters across 600 films from 2014 to 2019 were LGBTQ; none were transgender. Only 1.9 percent of API characters from the top 500 movies from 2015 to 2019 were shown with a disability. A mere 19.6 percent of all API women were 40 years of age or older. The image of API characters is predominantly young and largely male, straight and able-bodied.”40

In particular, more narratives with intersectionality with LGBTQ+, disability, and mixed-race experience are imperative.

3. Tell Stories That Break or Subvert Stereotypes

This can be the creation of more content that actively breaks stereotypes and tropes, including:

- Working-class, loud, crass Asian families.

- Having more than one Asian actor in the main cast who grapples with issues unrelated to their race.

- Resilient but kind Asian heroines.

- Coming of age stories with young Asian women with agency over their own sexuality.

- Attractive—and still smart—Asian men.

- Asian himbos.

In addition to narrative solutions, structural solutions can also make the Hollywood system more equitable and diverse.

4. Hire Asian American Talent Behind the Camera

Media companies need to hire more Asian American creators and executives at all levels and give them meaningful positions. CAPE often gets asked to consult on projects much too late in the process, when few if any meaningful changes can be made. Asian American writers should be hired from the beginning, not just at the end for an authenticity pass. Writers need to stop being hired solely to “soy sauce,” or add cultural flavor, to the script at the final polish stage. This practice needs to end.

This questioning and reflection should also extend to the source material and the context in which it is created. Who gets to tell the story? Is the author of the intellectual property committing cultural appropriation?

Additionally, more positions should be given to Asian American crew members—casting directors, hair and make-up workers who know how to work with Asian hair and appropriately apply make-up on monolids, lighting crew who know how to light for different skin tones, set designers, costume designers, editors, marketing and publicity, and all others.

Actress and producer Sandra Oh shared her story about Season 3 of Killing Eve, “I remember talking to the sound people, it’s like, ‘Hey guys, you are layering in the sound of me wearing shoes in the house. I don’t wear shoes. My character doesn’t wear shoes. I know you don’t see the feet. But don’t layer in the sound of shoes in the house, because that doesn’t happen.’”41 She adds, “But maybe these people, mostly White English dudes, don’t know that. It’s something that you might not even think is important, but it is because that’s how we start building the nuance of a character.”42

5. Provide Equitable Pay

Emerging talent, including support staff, need to be paid a living wage. If the barriers to entry are prohibitive for people from less privileged backgrounds, a diverse pool of talent would be difficult to maintain.

In a survey from the #PayUpHollywood report, almost 80 percent of assistants reported making $50,000 or less; in Los Angeles County, $63,100 is considered low-income.43 Moreover, 35 percent of survey respondents reported making less than $30,000 in 2020.44 Many do not receive health benefits or sick days, and their vacation time is not guaranteed. In some cases, assistants also face abusive treatment from their bosses.

In the casting process, producers and casting directors should also consider any unequal expectations from Asian actors that are not expected from White actors–are they appropriately compensated for any additional work beyond acting? This includes, without limitation:

- Foreign language proficiency or fluency.

- Martial arts skills.

- Additional time and resources to train the right Asian actor.

- Support and resources for accent or language work.

- Work beyond the hired role (e.g., translating, cultural consulting).

For instance, Heroes’ Masi Oka reportedly translated his own lines into Japanese for the hit TV show.45 Many actors are also having to correct a costume design or a prop on set. While these are often spun as positive stories of collaboration, it begs the question—is the project benefiting from the actors’ free labor?

Conclusion

Representation in media, especially in narrative entertainment, has the ability to greatly influence society. It is time Asian Americans reclaim and combat the harmful, stereotypical narratives in order to craft a better world and an inclusive community for tomorrow.

References

1. “FACT SHEET: Anti‐Asian Prejudice March 2020—Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism,” California State University, San Bernardino, Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, accessed 5 January 2022, 1, https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/FACT%20SHEET-%20 Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%203.2.21.pdf.

2. Aggie J. Yellow Horse et al., “Stop AAPI Hate National Report,” Stop AAPI Hate, accessed 5 January 2022, 1, https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Stop-AAPI-Hate-National-Report-Final.pdf.

3. Deepa Shivaram, “Olympic Gymnast Sunisa Lee Says She Was Pepper-Sprayed in a Racist Attack in LA,” NPR, 12 November 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/11/12/1055062621/ olympic-gymnast-sunisa-lee-says-she-was-pepper-sprayed-in-a-racist-attack-in-la.

4. David Livingstone Smith, “‘Less Than Human’: The Psychology Of Cruelty,” NPR, 29 March 2011, https://www.npr.org/2011/03/29/134956180/criminals-see-their-victims-as-less-than-human.

5. Brian Resnick, “The Dark Psychology of Dehumanization, Explained,” Vox, 7 March 2017, https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/3/7/14456154/dehumanization-psychology-explained.

6. Nancy Wang Yuen et al., “The Prevalence and Portrayal of Asian and Pacific Islanders across 1,300 Popular Films,” USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, May 2021, 10, https://assets.uscannenberg.org/docs/aii_aapi-representation-across-films-2021-05-18.pdf.

7. MAKERS: Geena Davis, YouTube, Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, 1 August 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YvbcMJbI80&ab_channel=GeenaDavisInstitute.

8. “Assessment of Audience Estimates During COVID-19,” The Nielsen Company (US), LLC, April 2021, 17, https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/04/2020-2021-Nielsen-National-TV-COVID-Evaluation.pdf.

9. George Gerbner and Larry Gross, “Living With Television: The Violence Profile,” Journal of Communication, ( June 1976): 182, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1976.tb01397.

10. Ibid.

11. Buck Gee and Denise Peck, “Asian Americans Are the Least Likely Group in the US to Be Promoted to Management,” Harvard Business Review, 31 May 2018, https://hbr.org/2018/05/asian-americans-are-the-least-likely-group-in-the-u-s-to-be-promoted-to-management.

12. William Pettersen, “Success Story, Japanese-American Style; Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” The New York Times, 6 January 1966, https://www.nytimes.com/1966/01/09/archives/success-story-japaneseamerican-style-success-story-japaneseamerican.html.

13. Kat Chow, “‘Model Minority’ Myth Again Used As A Racial Wedge Between Asians And Blacks,” NPR, 19 April 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/04/19/524571669/model-minority-myth-again-used-as-a-racial-wedge-between-asians-and-blacks.

14. Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo, “Income Inequality in the US Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians,” Pew Research Center, 12 July 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. “Fighting for Equal Pay for AAPI Women,” National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum, accessed 5 January 2022, https://www.napawf.org/equalpay.

18. Robin Bleiweis, “The Economic Status of Asian American and Pacific Islander Women,” The Center for American Progress, 4 March 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/economic-status-asian-american-pacific-islander-women/.

19. Dedrick Asante-Muhammad and Sally Sim, “Racial Wealth Snapshot: Asian Americans and the Racial Wealth Divide,” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 14 May 2020, https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-asian-americans-and-the-racial-wealth-divide/.

20. Victoria Namkung, “The Model Minority Myth Says All Asians Are Successful. Why That’s Dangerous,” NBC News, 20 March 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/model-minority-myth-says-asians-are-successful-dangerous-rcna420.

21. Stefanie K. Johnson and Thomas Sy, “Why Aren’t There More Asian Americans in Leadership Positions?,” Harvard Business Review, 19 December 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-arent-there-more-asian-americans-in-leadership-positions.

22. Erika Lee, “Chinese Immigrants in Search of Gold Mountain,” in The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2016), 59-76.

23. Dan Brekke, “Boomtown, 1870s: ‘The Chinese Must Go!’,” KQED, 12 February 2015, https://www.kqed.org/news/10429550/boomtown-history-2b.

24. Thomas Doherty, “Fifty Shades of Yellow: DeMille’s Orientalism,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 24 January 2016, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/fifty-shades-of-yellow-demilles-orientalism/.

25. Sabrina Qiao, “Fire Breathing ‘Dragon Ladies’: Representations of Asian American Women in Media,” The Pennsylvania State University (Archiving Asian American Literatures, 19 April, 2016), https://sites.psu.edu/engl428/2016/04/19/fire-breathing-dragon-ladies-representations-of-asian-american-women-in-media-overview/.

26. Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 US 275 (1875).

27. Luibhéid Eithne, “A Blueprint for Exclusion,” in Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 37.

28. Ray Cavanaugh, “Mata Hari’s True Story Remains a Mystery 100 Years After Her Death,” Time, 13 October 2017, https://time.com/4977634/mata-hari-true-history/.

29. India Roby, “Hollywood Played a Role in Hypersexualizing Asian Women,” Teen Vogue, 24 March 2021, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/hollywood-hypersexualizing-asian-women.

30. Thuc Nguyen, “Those 5 Words,” Esquire, 26 May 2021, https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/ a36547764/those-5-words-stop-saying-me-love-you-long-time/.

31. Nancy Wang Yuen et al., “The Prevalence and Portrayal,” 6.

32. “I Am Not a Fetish or Model Minority: Redefining What It Means to Be API in the Entertainment Industry,” Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, 2021, 26, https://seejane.org/wp-content/uploads/api-study-2021-8.pdf.

33. Aaron Feis, “Atlanta Spa Shooting Suspect Robert Aaron Long Had ‘Bad Day’ Before Massacre: Cops,” New York Post, 17 March 2021, https://nypost.com/2021/03/17/atlanta-shooting-suspect-had-a-really-bad-day-before-massacre-cops/.

34. Aggie J. Yellow Horse et al., “Stop AAPI Hate National Report,” 2.

35. Erika Lee, “Chinese Immigrants in Search of Gold Mountain,” in The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2016), 75-77.

36. Nathan Liu, “Sessue Hayakawa: America’s Forgotten Sex Symbol,” ACV, 10 December 2019, https://www.asiancinevision.org/sessue-hayakawa-americas-forgotten-sex-symbol/.

37. Maria Lewis, “Early Hollywood and the Hays Code,” ACMI, 14 January 2021, https://www.acmi.net.au/stories-and-ideas/early-hollywood-and-hays-code/.

38. Nancy Wang Yuen et al., “The Prevalence and Portrayal,” 23.

39. “Resources: Think Tank for Inclusion & Equity Fact Sheets on East Asians, South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Native Hawaiians & Pacific Islanders.” CAPE, accessed 5 January 2022. https://www.capeusa.org/resources-1.

40. Nancy Wang Yuen et al., “The Prevalence and Portrayal,” 13.

41. Elena Nelson Howe, “Sandra Oh Layers in Her Ethnicity on ‘Killing Eve’ Because White Hollywood Does Not,” Los Angeles Times, 23 June 2020, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-06-23/sandra-oh-layers-ethnicity-for-nuance-killing-eve.

42. Ibid.

43. Katie Kilkenny, “Hollywood Assistants Speak Out Over Low Pay, Start Hashtag,” The Hollywood Reporter, 16 October 2019, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/payuphollywood-hashtag-shines-a-light-low-assistant-pay-1247572/.

44. Liz Alper, “The 2020 #PayUpHollyWood Survey Results Are Here,” Medium, 1 February 2021. https://lizalps.medium.com/the-2020-payuphollywood-survey-results-are-here-3e5c6be8744f.

45. Susan Stewart, “A Surprise TV Star Embraces His Geeky Side,” The New York Times, 4 December 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/04/arts/television/04oka.html.