Abstract

The shooting and killing of Mike Brown by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, drew national attention to issues of discrimination, police brutality, and the growing divide between communities and their local law enforcement agencies. Compounding this with the grand jury’s decision not to indict the officer responsible, the need for police reform became evident. On the national level, reform focused on requiring body-mounted cameras on patrolling officers to provide better evidence for these cases. However, as this article argues, body cameras alone will not improve policing without also engaging the community—the people most affected by these issues.

This article outlines the costs of body-mounted cameras in Ferguson and proposes creating a police oversight commission consisting of the police commissioner, two patrolling officers, and six local community members to establish guidelines for use of body cameras, to investigate police misconduct, and to review complaints found “not sustained” by the Ferguson Police Department. By externalizing accountability mechanisms, this participatory structure makes police officers more directly accountable to the community and engages the key stakeholders—the community—in decisions about local policing.

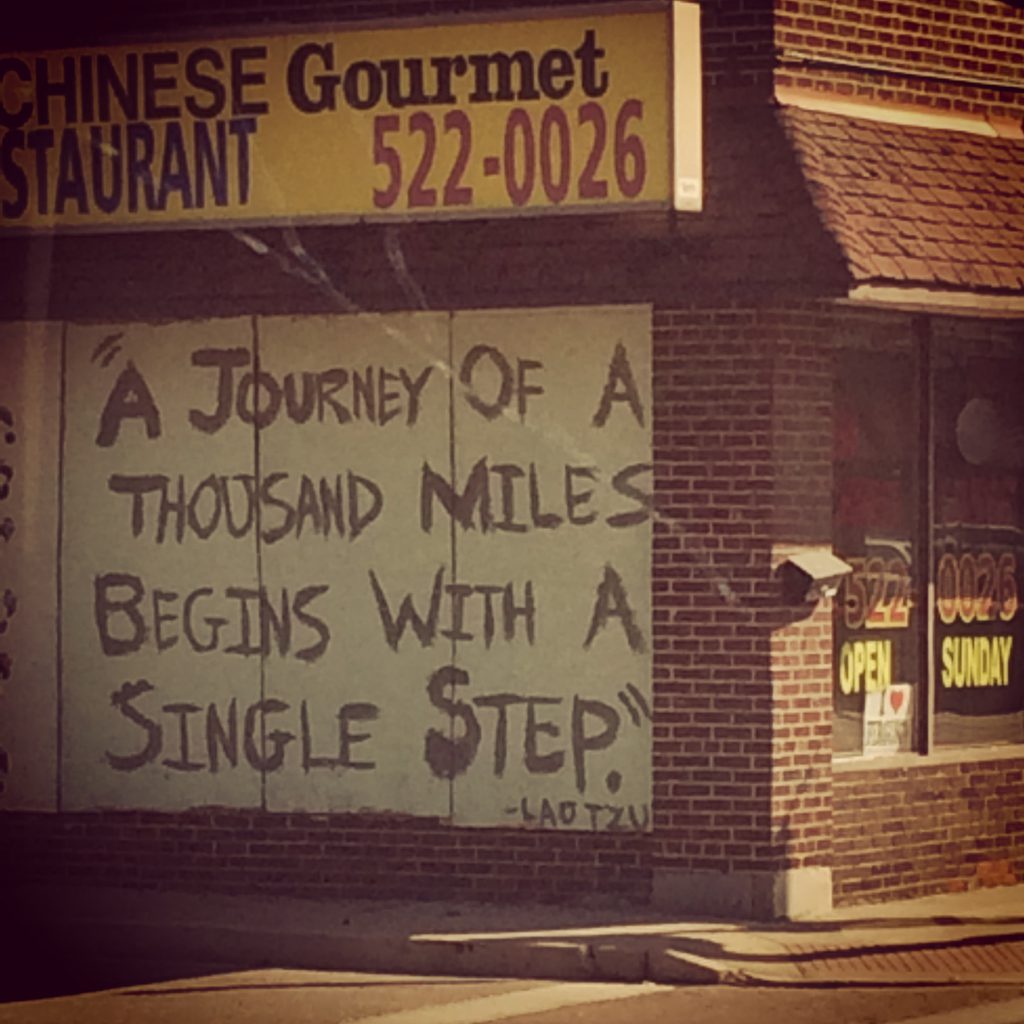

I visited Ferguson, Missouri, in late February, long after the cameras had left and supporters from out of town had taken their buses home, and I found a story that hadn’t been told. Community members had banded together to cover the windows that had been broken on local storefronts so the businesses wouldn’t lose heat. Then, once all the windows had been covered, community members had grouped together to paint and beautify the area, painting over the dull boards with messages of hope and community. A main window that had been broken on a Chinese restaurant had been repaired and now read, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” a quote from Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching.

Hundreds of boards had been painted throughout Ferguson in this way, some with rainbows, others with images of civil rights leaders and their messages. Where there had been broken glass and burned wood there were now messages of hope. And when members of the community saw a board they had painted, they felt a new type of ownership over their community. No top-down plan to revitalize the area could have been as cost-effective or engaging as this community-driven effort. This made me consider the national policy to implement body cameras within local law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and to consider the viability of this in Ferguson and the ways in which it could include a similar level of community engagement.

Mike Brown’s parents requested that the death of their son be a catalyst for national systemic policy change, and one of their main objectives was to see the implementation of body-mounted cameras within law enforcement agencies. The Obama administration recently announced a $263 million commitment over the next three years to offer funding for LEAs that purchase body-mounted cameras for their officers.[1] The policy proposal below investigates the costs of this body camera implementation within Ferguson’s police department and proposes a component of all this that has been painfully overlooked—community involvement.

Community members need to be a part of a review board that monitors footage taken from body-mounted cameras placed on police officers. If internal police review boards are the only ones seeing such footage, it’s unlikely that this policy will have its desired impact. So with that in mind, the proposal below reimagines and outlines a new vision of community policing for Ferguson.

Purpose

Body cameras on patrolling officers combined with the creation of a community oversight council will improve community relations with law enforcement, reduce the number of violent interactions, and restore public confidence in law enforcement.

Background and Context

The grand jury decision in Ferguson not to indict the officer responsible for shooting and killing Michael Brown, an African American male teenager, has sparked outrage, polarizing the country in the process. The prosecuting attorney released the evidence presented to the grand jury, and witness testimonies told divergent accounts of the events.[2] Unable to separate fact from fiction, the grand jury ruled against indictment. In the wake of the decision, the family of Michael Brown urged citizens to channel any frustration into positive change and to join the campaign to ensure every police officer working the streets in this country wears a body camera.

In the aftermath of the Eric Garner case, where the grand jury also decided against indictment despite video evidence that the police caused a man to suffocate to death, it has become obvious that in addition to body cameras, reform requires a structural change to police oversight to give the community a greater voice in these matters. To accomplish this goal, many cities have already established a participatory oversight council, such as the Office of Police Complaints in Washington, DC, the Office of Citizen Complaints in San Francisco, and the Community Ombudsman Oversight Panel in Boston.

The deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner are not isolated events. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) data on police shootings shows a Black teenager is shot and killed twice a week, even despite the fact that less than 5 percent of law enforcement agencies contributed to the database.[3] Recent events have initiated a national dialogue on race, discrimination, and police brutality; this conversation must now be converted into substantive change.

The Policy

This policy requires police officers in Ferguson to wear a body camera that records video and audio while on patrol. Additionally, in order to implement this new technology, the city of Ferguson will establish a police oversight commission (POC) consisting of the police commissioner, two patrolling officers, and six local community members. The police commissioner appoints two patrolling officers for the committee, and community members are elected. The POC will establish guidelines for use of body cameras and footage, investigate police misconduct, and review complaints found “not sustained,” “unfounded,” or “exonerated” by the Ferguson Police Department.

Analysis

Body cameras are a low-cost alternative to police militarization. Each body camera costs $300-$400 from producers such as Taser International, Inc., or Vievu LLC. The city of Ferguson has eight to twelve officers patrolling at any given time and employs forty-two officers total;[4] therefore, the costs of ensuring body cameras for each patrolling officer amounts to $3,600-$4,800, plus the cost of data storage. The cost would be even lower for Ferguson since the city began purchasing body cameras prior to the shooting of Michael Brown but has not begun using them.

This is a small price, especially when considering the benefits. Research by Cambridge University on the introduction of body cameras in Rialto, California, revealed very positive effects: in the first year alone, the number of incidents of police force declined 60 percent and the number of complaints filed by civilians decreased 90 percent.[5] This suggests officers are more reluctant to use violence as a solution and citizens are more satisfied with the quality of policing. In contrast, without the documentation provided by body cameras, police militarization heightened tensions and turned Ferguson into a war zone.

To put this in perspective, Ferguson allocated $50,600 to police equipment in 2014.[6] Part of the funds for military-grade equipment could be diverted to cover the entire costs of body cameras. In the riots following the death of Michael Brown, a police officer in Ferguson was photographed carrying a $1,200 M4 5.56 mm Carbine rifle, two pistols at $500 each, and 180 rounds of ammunition.[7] This officer carried $2,200 worth of military-grade firearms, and as residents will remark, this officer was not alone. At the cost of four Carbine rifles, Ferguson could finance body cameras.

Lastly, the creation of the POC ensures the community has a voice in these issues. A study by Archon Fung found more effective policing and improved community relations when a participatory council was implemented into the Chicago Police Department.[8] Boston, San Francisco, and Washington, DC, have all established similar participatory councils to improve accountability for police departments and have seen encouraging results.[9] This structure benefits from the technocratic knowledge of officers and engages stakeholders in finding a solution, ensuring the POC makes well-informed decisions on the use of body cameras with consideration for officers and the larger community. Additionally, externalizing oversight of the police department prevents the potential for corruption by making police more directly accountable to the community and transparent in their proceedings.

Requiring body cameras makes both officers and civilians accountable for their actions, and the POC supplements this change by allowing civilian oversight over any potential conflicts. This policy is a step in restoring confidence in our law enforcement and making it more accessible to citizens.

Next Steps

The campaign for body cameras has made progress, and President Obama announced in December a bill that would allocate $263 million in federal funds to local law enforcement agencies for this purpose.[10] However, cameras will not be enough. This issue requires systemic change to accountability mechanisms.

Potential partners to help build out support include Ferguson City Council member Keith Kallstrom, given his experience volunteering for community policing efforts. ArchCity Defenders, a nonprofit organization in St. Louis, has campaigned for similar reforms and offers valuable resources and contacts.

Key Facts

- Body cameras for every patrolling officer in Ferguson would cost around $4,800, or less than 10 percent of the department’s $50,600 budget for policing equipment.

- Federal government spent $5.1 billion on military-grade equipment for local authorities since 1990.[11]

- Introduction of body cameras reduced incidents of police force by 60 percent and number of complaints by 90 percent in Rialto, California.[12]

Talking Points

- Body cameras are a less expensive and more effective alternative to police militarization.

- Data from cameras would provide an objective account of events to the court and reduce the uncertainty in trial.

- Body cameras hold police officers and civilians accountable for their actions, which will help restore our faith in the law enforcement and court systems.

- Studies show body cameras reduce the number of violent interactions with police and the number of complaints filed by citizens.

- Police oversight councils increase citizen oversight over police officers; councils proved successful in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

Action Plan

- Community outreach. Continue to build a diverse coalition of activists, legislators, and local businesses to support the policy. The community wants to affect change but needs a constructive proposal to build on.

- Policy affairs. City council members who enact legislation already feel pressured by the community to take action. It is imperative to shift the current momentum to focus on a constructive proposal.

- Coalition building. Continue to build support in the community by reaching out to local businesses, nonprofits, legislators, and activists. People demonstrated passion for this issue, but this movement needs an agenda.

- Communication plan. The campaign will focus its message on learning from recent events by providing video evidence for any future incidents and making police officers more directly accountable to the community they serve.

Timeline

Over the next few months, the coalition must continue to be built out. By the summer, the coalition should be strong enough to pressure legislators to pass the body cameras and create the POC.

Endnotes

[1] Nolan Feeney, “Obama Requests Funds for Police Body Cameras to Address ‘Simmering Distrust’ After Ferguson,” Time, 1 December 2014.

[2] Eyder Peralta and Krishnadev Calamur, “Ferguson Documents: How the Grand Jury Reached a Decision,” The Two-Way, National Public Radio, 25 November 2014.

[3] Kevin Johnson, Meghan Hoyer, and Brad Heath, “Local Police Involved in 400 Killings Per Year,” USA Today, 15 August 2014.

[4] City of Ferguson, Missouri, “Annual Operating Budget, Fiscal Year 2013-2014,” City of Ferguson.

[5]Tony Farrar, Self-Awareness to Being Watched and Socially-Desirable Behavior: A Field Experiment on the Effect of Body-Worn Cameras on Police Use-of-Force, Police Foundation, March 2013.

[6] City of Ferguson, “Annual Operating Budget 2013-2014.

[7] Paul Szoldra, “This is the Terrifying Result of the Militarization of Police,” Business Insider, 12 August 2014.

[8] Archon Fung, “Accountable Autonomy: Empowered Deliberation in Chicago Schools and Policing,” Politics and Society 29, no. 1 (2001): 73-103.

[9] Christopher Stone, An Assessment of the Community Ombudsman Oversight Panel, Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, April 2009.

[10] Feeney, “Obama Requests Funds for Police Body Cameras.”

[11] Al Jazeera staff, “Congress Scrutinizes Police Militarization Before Planned Ferguson Protest,” Al Jazeera, 10 September 2014.

[12] Farrar, Self-Awareness to Being Watched and Socially-Desirable Behavior.