BY ALEXANDER SMITH

Gone are the days of American criminals like Al Capone, John Gotti, and Bonnie and Clyde. Recent prosecutorial practices of US regulatory agencies suggest that modern America now confronts an entirely new class of “criminal.” They are listed on national stock exchanges, occupy flashy corporate headquarters, and are run by individuals adorned with white collars and pinstriped suits. After years of financial market scandals, environmental catastrophes, and disregard for consumer safety, recent years have seen an unprecedented wave of criminal prosecutions brought by US regulators against some of the world’s largest corporations.

Prosecuting corporations for criminal wrongdoing is not new, but companies now operate in a modern regulatory environment that is incredibly complex. Over 300,000 US regulatory provisions currently carry criminal penalties, making compliance a struggle for even the most sophisticated institutions.[i] Given firms’ desire to avoid the expense and uncertainty of court battles, the troubling incentives of the US legal system allow prosecutors to threaten legal action in order to force firms into lucrative out-of-court settlements. These confidential deals rarely shed light on the facts of a case and very few individuals are ever actually charged with wrongdoing.[ii]

As the regulatory process becomes troublingly opaque and capricious, policymakers should ask whether justice is actually being served by increasing efforts to criminalize corporate America. Allowing regulators to continue to extract mob-like ransom payments from corporations risks degrading the integrity of the US legal system and fostering an opportunistic environment that threatens to undermine due process and the rule of corporate law. While today’s corporate “criminals” may not look like the gangsters of old, policymakers should be worried by the justice system’s newfound reliance on the familiar tactics of extortion and blackmail.

Law and Corporate Disorder

| Aggregated Fines by Institution | |

|

Financial Institution |

Amount |

| Bank of America | $57.9 billion |

| JP Morgan Chase | $32.2 billion |

| Citigroup | $12.8 billion |

| Wells Fargo | $9.67 billion |

| BNP Paribas | $8.9 billion |

| Deutsche Bank | $4.5 billion |

| Credit Suisse | $4.35 billion |

| UBS | $4 billion |

| RBS | $2.18 billion |

| Goldman Sachs | $2.17 billion |

| Morgan Stanley | $1.9 billion |

| Barclays | $1.6 billion |

| Standard Chartered | $1 billion |

| Table 1: Aggregated Fines by Institution 2008-2015 (Data: Financial Times) | |

Regulation through prosecution has become big business in America. And in recent years, business has been booming. In 2014, Citigroup paid $7 billion to settle allegations that it misled investors over the sale of mortgage backed securities, while BNP Paribas forked out $8.9 billion for violating sanctions against Sudan.[iii] Since 2008, JP Morgan Chase alone has settled nearly forty separate claims with US regulators at a cost of over $32 billion. Bank of America reached the largest settlement between US regulators and a single company at $16.65 billion, and has coughed up a staggering total of almost $60 billion to a slew of regulators. Since the financial crisis unfolded in 2008, US regulators have extracted over $160 billion in fines and settlements from banking institutions alone.[iv] (See Table 1)

And it is not just the financial sector that has found itself on the wrong side of regulators. In 2014, after Toyota acknowledged safety defects in its vehicles, the US Department of Justice used wire fraud charges against the company to extract a record $1.2 billion settlement under a Deferred Prosecution Agreement.[v] Similarly when General Motors found itself in the spotlight for ignition switch defects in its cars, it signed an agreement in 2015 under which it agreed to pay regulators $900 million.[vi] It is no wonder that Volkswagen has readied $7.3 billion for an expected wave of criminal settlements following the emissions scandal that rocked the company in 2015.[vii]

America’s Pinstriped Prison

Not only have corporate fines risen inexorably higher, the nature of legal action taken against firms has also changed.[viii] Remarkably few of the mammoth settlements mentioned above resulted in adjudicated legal proceedings against any individuals. Instead, prosecutors have preferred to pursue the corporate entities themselves.[ix] Under US law, corporations are treated as separate legal “persons” distinct from their owners and managers, meaning it has long been possible to hold corporations criminally liable—even for actions allegedly committed by a single employee.[x] While the word “corporation” derives from the Latin word for “body” (corpus), regulators have discovered it is considerably more complex to impose criminal liability on corporations because companies have “no soul to be damned, no body to kick.”[xi] Thus, it is natural to ask with all this alleged criminal behavior happening, who is actually going to prison? Well, usually no one.[xii] Prosecutions rarely end up in court because lawsuits are simply bad both for business and share prices.[xiii] The emergence of civil class actions long ago taught corporate executives that when a discreet settlement is on the table, you take it, pay for it, and move on.

Regulators increasingly rely on Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs) and Non-Prosecution Agreements (NPAs) to settle disputes discreetly, with over three hundred such agreements having been executed in recent years.[xiv] In return for the target company paying fines and conducting other remedial actions, prosecutors agree to suspend the case pending court approval. Prosecutors wield enormous amounts of power under these settlement mechanisms as they can impose fines, compliance conditions, and suspensions or revocations of trading licenses.[xv] The use of DPAs and NPAs in lieu of prosecutions in white-collar practice has become so frequent that some legal experts have said that they represent the most significant change in corporate law enforcement policy in the past decade.[xvi]

Distinguishing between Reasonability and Racketeering

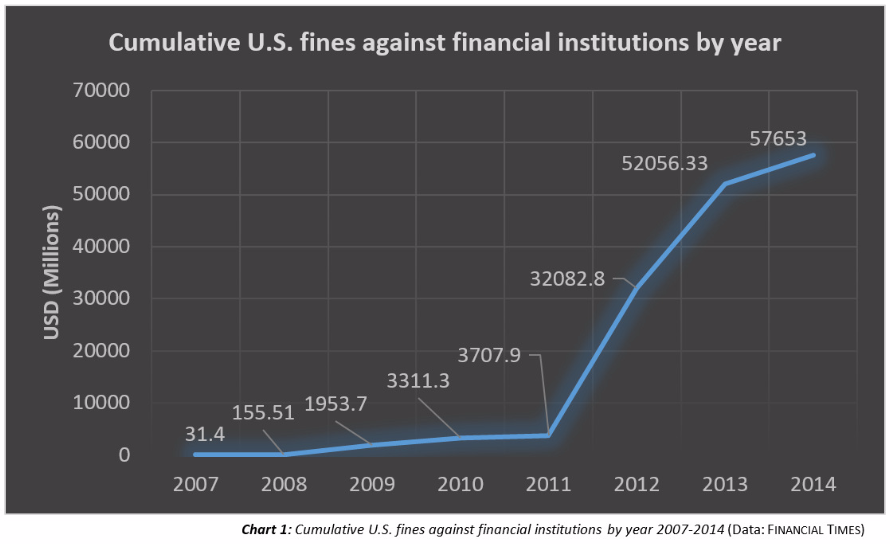

Companies ought to be punished when they break the law and US regulators’ ability to criminally charge corporations comprises an important part of the “stick” that underpins modern corporate law. In many instances, corporations’ gross misconduct and willful negligence renders it appropriate to greet these defendants with the full strength of the law. But the prosecutorial practices of US regulators increasingly resemble an extortion racket.[xvii] As Chart 1 demonstrates, the recent scale of prosecutorial operations and the quantum of settlements ought to make policy makers ask whether the basic objectives of a coherent legal system are being met—the need to punish and deter corporate misconduct; to encourage stronger corporate governance and regulatory compliance; and to protect and compensate consumers, where appropriate.

Spearheaded by the DOJ’s Financial Fraud Enforcement Task Force, opaque charges are regularly levied against corporations, billions of dollars and admissions are extracted behind closed doors, and consumers who were wronged are too often left empty handed.[xviii] As The Economist has observed, a troubling pattern of regulatory behavior has emerged: regulators identify a large corporation that may or may not have engaged in wrongdoing; bully its managers with threats of financial ruin and criminal charges; negotiate a settlement preserved by a seal of confidentiality; extract vast sums of money; and then look for a new target.[xix] Current practices ought to raise policymakers’ eyebrows for several reasons.

First, the prosecutorial process, and its reliance on DPAs and NPAs, suffers from an appalling absence of transparency. In an environment where multi-billion dollar settlements are being regularly concluded beyond the view of judicial officers, no trials take place, there is no way of knowing whether evidence is properly scrutinized, and too few questions are asked by those in a position to monitor US regulators.[xx] When the prospect of criminal liability is introduced, the risk becomes so great that firms will—and do—pay billions of dollars to avoid even a remote possibility of an adverse finding. One need only reflect on the 2002 criminal trial of the accounting giant Arthur Andersen for its alleged role in the downfall of Enron in order to understand the prudence behind modern firms’ risk aversion.[xxi] When Arthur Andersen refused a last minute settlement offer, the subsequent guilty verdict led to the catastrophic collapse of the firm—notwithstanding the fact that the criminal conviction was later overturned on appeal.[xxii] Corporations are so willing to settle with prosecutors because confidential settlements provided by DPAs and NPAs offer reputational protection, minimize exposure to legal costs, and are driven by firms’ rational aversion to litigation risk. But this means that firms are rendered liable to extortion by regulatory bodies behind closed doors where settlements are concluded without the legitimacy of the underlying charges being explored or adjudicated upon in an open and impartial setting.

Secondly, we ought to question our collective comfort with public officials condoning, if not encouraging, corporations to settle criminal charges against them via monetary payments. In cases where a prosecutor determines that it is appropriate to bring criminal charges against a corporation for egregious misconduct, it is not at all clear why policymakers should then effectively allow a company to pay its way out of criminal liability. The willingness of regulators to settle corporate criminal charges raises the question of whether such practices constitute a white-collar subversion of justice. Unlike civil claims, it is generally not possible for individual citizens to buy their way out of a criminal prosecution. This is because, in principle, criminal charges seek to pursue a variety of public justice objectives, rather than merely extracting civil remedies like monetary compensation. Although raising criminal charges often enables prosecutors to threaten companies with larger financial sanctions that would otherwise not be possible, we should feel deeply uncomfortable with authorities threatening criminal sanctions in circumstances where there is no legitimate intention to pursue them to trial because such practices are tantamount to blackmail and subvert the integrity of the judicial system.[xxiii] Our level of discomfort ought to rise even further when regulatory agencies seek to enter state-sanctioned settlements that enable executives to purchase a “get out of jail” card using company shareholders’ resources.

| Repeat Offenders:Number of Settlements by Institution | |

| Financial Institution | Number |

| JP Morgan Chase | 39 |

| Bank of America | 20 |

| Wells Fargo | 17 |

| Citigroup | 16 |

| Barclays | 14 |

| UBS | 11 |

| RBS | 10 |

| HSBC | 10 |

| Deutsche Bank | 8 |

| Morgan Stanley | 8 |

| Credit Suisse | 8 |

| Goldman Sachs | 7 |

| Table 2: Repeat Offenders—Number of Settlements by Institution 2008-2015 (Data: Financial Times) | |

Thirdly, it is rarely clear how prosecutors exercise their discretion when they determine settlement amounts and how they decide whether to continue a prosecution against a defendant. This leaves the process exposed to accusations that many of the astronomically large fines paid under settlement agreements are arbitrarily determined.[xxiv] Indeed, prosecutors are not required to give justification for the fines they seek and, therefore, rarely volunteer explanations with specificity.[xxv] Admittedly, it is immensely difficult to quantify the harm inflicted by a financial institution when it breaches US sanctions or misleads investors over mortgage-backed securities. However, prosecutors should not shirk their duty to provide specific justification for the fines levied, and ought to adhere to more robust settlement principles. As law professor Brandon Garrett has commented, prosecutors “offer corporations leniency and forego prosecutions in exchange for ill-defined compliance and rarely useful cooperation in pursuing charges against individual employees.”[xxvi] The absence of clarity further opens the process to accusations that regulators are engaging in a form of opportunistic rent extraction.

Finally, one might reasonably expect that the eye-popping size of fines in recent years would serve as a sufficiently strong deterrent against misconduct, and perhaps even an incentive for firms to improve corporate compliance. But recent experience suggests otherwise. As Table 2 indicates, a glance at recent settlements exposes the repeat patronage of defendants such as JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. Whether the policy objective underlying huge fines is rehabilitating the defendant or deterring other would-be corporate criminals, policymakers ought to ask how current practices affect corporate governance and compliance. It is not clear whether large fines actually deter corporate executives and boards from misconduct and cause them to tighten their ships, or whether it is simply seen a new cost of doing business in America. The figures in Table 2 suggest the latter and, therefore, could be said to undermine much of the justification offered by regulators for extracting billions of dollars in shareholder value in the first place.

Following the Money

Given all these problems, why do US regulators remain so ready to reach for criminal enforcement proceedings to address corporate misconduct? The perverse incentive structure of the American legal system deserves much of the blame. In many instances, if prosecutors do not levy criminal charges, then enforcement is often limited to restitutionary actions and is bound by relatively small civil penalty caps.[xxvii] Indeed, the US Securities and Exchange Commission, which is generally limited by law to imposing relatively small civil fines for securities fraud, is far less likely than other regulators to resort to DPAs.[xxviii]

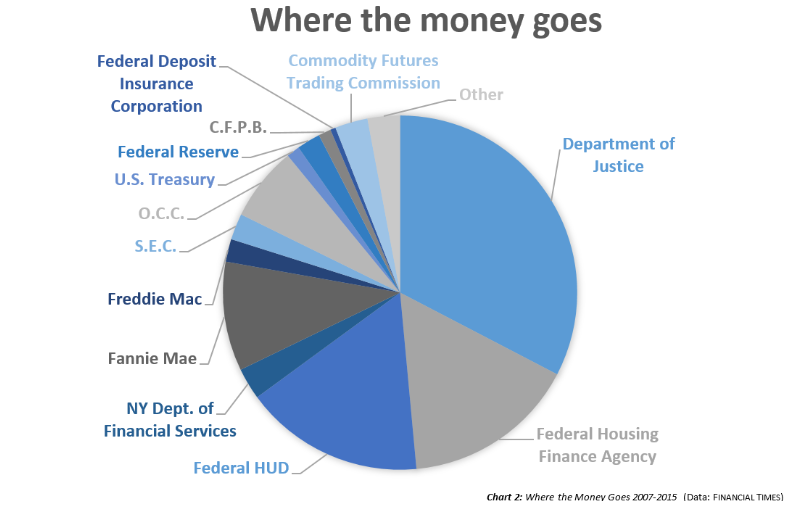

Public authorities have become addicted to revenues from corporate fines. As Chart 2 demonstrates, some regulatory agencies have come to resemble profit centers. Evidence suggests that states like New York, for example, regularly earmark such funds for general expenditure, applying the proceeds to services such as “housing and related purposes.”[xxix]

This practice risks engraining dependence on a source of revenue that is unpredictable and arbitrarily derived, and threatens to instill a system of perverse incentives for prosecutors and the agencies they serve. Public authorities must be accountable for how funds from enormous fines are allocated. For example, of the billions of dollars extracted by the DOJ via settlements and judgments in 2011, only $116 million was paid to victims as restitution.[xxx] It is one thing to use proceeds from fines to compensate consumers or to refund public pensions depleted after banks misled public investors. We should, however, feel far less comfortable with public authorities treating such funds as a source of ordinary revenue.

Where to from Here?

The prosecutorial practices of US regulators must change. It is apparent that the use of criminal charges may not be an appropriate tool to achieve justice and redress corporate misconduct in many instances. Yet, current practices will likely continue unless policymakers move to bolster the non-criminal alternatives available to regulators. Regulatory agencies like the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are understaffed and lack the resources required to monitor and effectively enforce the hundreds of thousands of legal provisions governing an increasingly complex and sophisticated US corporate sector.[xxxi] Lawmakers must empower agencies like the SEC to levy far larger civil penalties against the companies they are supposed to be monitoring—powers that regulators have long requested.[xxxii]

Lawmakers and judicial officers ought to question the economic rationale behind some of the large fines that are being handed out and declare that discretionary charges brought by prosecutors who have no intention of going to trial is a practice that degrades the rule of law and ought to be stopped. Greater transparency and judicial oversight needs to be injected into the system. This requires that policy makers and legislators hold public agencies to higher standards by demanding that clear grounds for prosecution be established from the outset, and that public agencies be forced to disclose how they allocate the billions of dollars they extract. And when executives are found to have committed criminal acts, they should not be able to use shareholders’ resources to purchase expensive “get out of jail” cards and be left to go about their business.

As privileged creatures of statute, modern corporations are extended so many benefits under law that it is entirely reasonable for regulators to hold them to the highest standards. But in a country that prides itself on transparency, accountability and the rule of law, corporate “justice” cannot be allowed to continue to consist of coercion behind closed doors.

Just when the banks thought the bills for their pre-crisis shenanigans had finally stopped coming, the U.S. Department of Justice struck again. In late September 2016, Deutsche Bank confirmed that U.S. regulators are seeking $14 billion to settle claims relating to Deutsche’s pre-crisis sale of mortgage backed securities.

Naturally, few may be inclined to complain about public regulators frequently whacking big banks with huge fines, particularly during a time of sclerotic growth and populist politics. But opaque prosecutorial practices and questionable economic rationales should lead policy-makers to reassess their comfort levels in leaving prosecutors to ride dubious settlement payments all the way to the bank. It’s time to put U.S. practices under the microscope and examine exactly what type of justice is being dispensed.

Alexander practiced as a commercial lawyer in Australia. He holds a Master of Public Policy from Harvard University and a Master of Law from the University of Cambridge. Alexander currently lives and works in California.

Photo Credit: Unsplash

[i] Paul Rosenzweig, One Nation Under Arrest: How Crazy Laws, Rogue Prosecutors, and Activist Judges Threaten Your Liberty (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, 2013). http://www.amazon.com/One-Nation-Under-Arrest-Prosecutors/dp/0891951342.

[ii] Brandon L. Garrett, Too Big To Jail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

[iii] US Department of Justice, United States v. BNP Paribas S.A.: Plea Agreement, 27 June 2014 [https://perma.cc/P3DW-8JRC].

[iv] Martin Stabe and Aaron Stanley, “Bank Fines: Get the Data,” Financial Times, 22 July 2015 [http://blogs.ft.com/ftdata/2015/07/22/bank-fines-data/].

[v] “Justice Department Announces Criminal Charge Against Toyota Motor Corporation and Deferred Prosecution Agreement with $1.2 Billion Financial Penalty,” United States Department of Justice (19 March 2014) [https://perma.cc/2NMA-4TV5].

[vi] “US Attorney of the Southern District of New York Announces Criminal Charges Against General Motors and Deferred Prosecution Agreement with $900 Million Forfeiture,” United States Department of Justice (17 September 2015) [https://perma.cc/4N5G-LCU9].

[vii] The Economist Editorial Staff, “Good in Parts,” The Economist, 3 October 2015 [https://perma.cc/C2EZ-K93X].

[viii] June Rhee, “Justice Deferred is Justice Denied,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, 3 November 2014.

[ix] Jed S. Rakoff, “The Financial Crisis: Why Have No High-Level Executives Been Prosecuted?,” New York Review of Books (9 January 2014) [https://perma.cc/M4FU-EVRC].

[x] United States Code, s. 1; New York Central & Hudson River Railroad v. United States 212 US 481 (1909); Brandon L. Garrett, Too Big To Jail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 1.

[xi] Lord Chancellor of England, Edward, First Baron Thurlow, Quoted in M. King, Public Policy and the Corporation 1 (1977); John C. Coffee, “No Soul to Damn: No Body to Kick: An Unscandalised Inquiry into the Problem of Corporate Punishment,” Michigan Law Review 79 (1980): 386; Garrett, Too Big to Jail.

[xii] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 13.

[xiii] John Armour, Colin Mayer, and Andrea Polo, “Regulatory Sanctions and Reputational Damage in Financial Markets,” Oxford Legal Studies Research Paper No. 62/2010 [http://ssrn.com/abstract=1678028].

[xiv] Brandon L. Garrett and Jon Ashley, “Federal Organizational Prosecution Agreements,” University of Virginia School of Law; The Economist Editorial Staff “Criminalising the American Company: A Mammoth Guilt Trip,” The Economist, 30 August 2014.

[xv] See, e.g., Ben Protess and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “Two Giant Banks, Seen as Immune, become Targets,” Dealbook (29 April 2014) [http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/04/29/u-s-close-to-bringing-criminal-charges-against-big-banks/]; The Economist Editorial Staff “Capital punishment,” The Economist, 5 July2014

[xvi] June Rhee, “Justice Deferred is Justice Denied,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, 3 November 2014.

[xvii] The Economist Editorial Staff “The Criminalisation of American Business,” The Economist, 30 August 2014.

[xviii] See Chart 2; see also John W. Schoen, “7 years on from crisis, $150 billion in bank fines and penalties,” CNBC (30 April 2015) [http://www.cnbc.com/2015/04/30/7-years-on-from-crisis-150-billion-in-bank-fines-and-penalties.html].

[xix] The Economist Editorial Staff “Corporate Settlements in the United States,” The Economist, 30 August 2014.

[xx] David M. Uhlmann, “The Pendulum Swings: Reconsidering Corporate Criminal Prosecution,” UC Davis Law Review 49(4) (Forthcoming) [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2642455].

[xxi] N. Craig Smith and Michelle Quirk, “From Grace to Disgrace: the Rise & Fall of Arthur Andersen,” Journal of Business Ethics Education 1 (2004): 91.

[xxii] The Economist Editorial Staff “Criminalising the American Company: A Mammoth Guilt Trip,” The Economist, 30 August 2014

[xxiii] Margaret H. Lemos and Max Minzner, “For-Profit Public Enforcement,” Harvard Law Review 127(3) (2014): 853.

[xxiv] The Economist Editorial Staff “The Criminalisation of American Business,” The Economist, 30 August 2014.

[xxv] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 6-18.

[xxvi] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 149.

[xxvii] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 267.

[xxviii] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 267.

[xxix] Christina Rexrode and Devlin Barrett, “Bank of America to Pay $17 Billion in Justice Department Settlement,” The Wall Street Journal, 20 August 2014.

[xxx] United States Department of Justice, “Department of Justice Secures More Than $2 Billion in Judgments and Settlements as a Result of Enforcement Actions Led by the Criminal Division,” Office of Public Affairs (press release), 21 January 2011. [https://perma.cc/796V-ZAPD].

[xxxi] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 266-268.

[xxxii] Garrett, Too Big to Jail, 267.