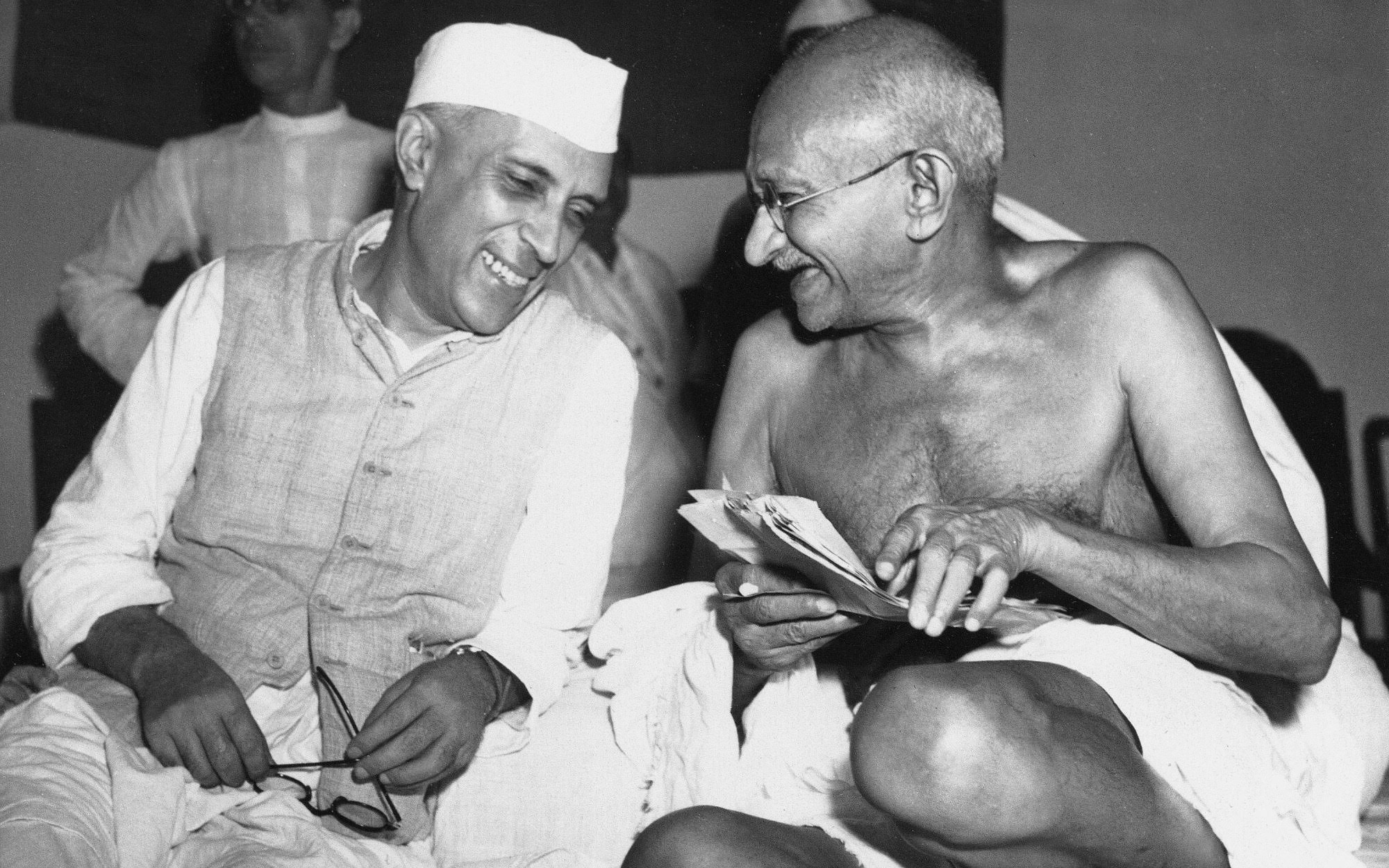

Photo Credit: Archives – The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library

By Vinay Nagaraju, MC/MPA and Mason Fellow 2017

For Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s march to freedom in August 1947 was also the beginning of a march out of Gandhi’s shadows. Gandhi was bitterly opposed to the two-nation theory and the “Mountbatten Plan” that accomplished the geographic partition of India, leaving him with few friends in the Indian National Congress. In the years leading up to the partition, the idealist Gandhi was sidelined and it was Jawaharlal Nehru who reluctantly agreed to the partition of the country, along with Muhammad Ali Jinnah representing the Muslim League (who goes on to become the first Prime Minister of Pakistan), Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar representing the untouchables, and other leaders. India was on the verge of a civil war, and communal violence had engulfed the country. A pragmatic Nehru struggled relentlessly to convince his mentor Gandhi of the inevitable division of the country, while taking the responsibility of leading a nation through this political turmoil.

India attained independence amidst a bloody partition, leaving it to Nehru alone to heal the wounds of a divided society. This time, there was a stark difference from the pre-independence era, when the leadership of the Gandhi-Nehru duo caught the public imagination. Gandhi now spent most of his time urging for Hindu-Muslim unity far away from New Delhi, the political capital, and continued his own spiritual quest. In Delhi, Nehru was slowly and steadily laying the foundations for a modern Indian state all by himself. The loneliness of Nehru’s leadership was telling.

Nehru was deeply troubled with the “disastrous happenings” in Punjab, the region most affected by the partition. He was unwilling to apportion any blame and “enter into an acrimonious debate about the past.” Instead, all his efforts were directed towards avoiding “complete chaos and ruin for the land and for every community.” He spoke on behalf of the Indian government, which was still an alien concept to the people of the country, saying his government “will treat every Indian on an equal basis and try to secure for him all the rights which he shares with others.” He emerged a visionary, urging and compassionately coercing people to subscribe to the new idea of India. The true mark of Nehru’s statesmanship was seen in these years of transition from British rule to self-determination. Even as he doused the flames of past divisions and united the people, he kept his focus on the future of the nation-state.

The reorganization of the states—an attempt to integrate the provinces of the British India and the princely states—was an opportune moment to define the character of the Indian Union. It was a formidable task that Nehru asked his lieutenant, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, to manage. Patel was considered by many to be the man who should have donned the mantle instead of Nehru as India’s Prime Minister, had it not been for Gandhi’s backing. However, it was Nehru’s vision of an Indian Union—with the states reorganized not on religious or ethnic identities, but on linguistic identities, while promoting an Indian nationalism—that remained the mainstay. Nehru’s leadership style was consummate. Despite the ideological differences and the fact that Patel was seen as his bête noire, he rose to the occasion, and took him as his confidant. Their partnership and leadership helped establish the Indian Union as we see it today, and ensured the smooth transfer of power from the French India and Portuguese India in subsequent years.

A secularist to the core, shaped partly by his education in the West, Nehru believed in the unity of the nation and often spoke against the hatred that was being spread across the country in the name of religious and political expression. When Gandhi was assassinated, he took pains to underscore this message even in a moment of deep disgust and rage, saying “A madman has put an end to his life, for I can only call him mad who did it, and yet there has been enough of poison spread in this country during the past years and months, and this poison has had an effect on people’s minds. We must face this poison, we must root out this poison, and we must face all the perils that encompass us, and face them not madly or badly, but rather in the way that our beloved teacher taught us to face them.”

The Patel and Nehru duo successfully led the reformation of the physical boundaries of the states and territories. The establishment of a secular and inclusive state was next on the foreground of Nehru’s mind. Speaking during a debate on a resolution on the “dangerous alliance of religion and politics,” he said, “The alliance of religion and politics in the shape of communalism is the most dangerous alliance, and it yields the most abnormal kind of illegitimate brood.”

In his message to an independent India, he had said, “The future beckons to us. Whither do we go and what shall be our endeavour? To bring freedom and opportunity to the common man, to the peasants and workers of India; to fight and end poverty and ignorance and disease; to build up a prosperous, democratic and progressive nation, and to create social, economic and political institutions which will ensure justice and fullness of life to every man and woman.” In his speech a year later to the Constituent Assembly, and in response to a resolution, he further elaborated on his views on affirmative action, expressing reservations for “the unfortunate countrymen of ours who have not had these opportunities in the past…” He cautions, however, that these external props “may possibly be helpful occasionally in the case of the backward groups, but they produce a false sense of political relation, a false sense of strength, and ultimately, therefore, they are not so nearly as important as real education, cultural and economic advance, which gives them inner strength to face any difficulty or any opponent.”

Previously, during Gandhi’s fast in Poona jail protesting Ambedkar’s idea of a separate electorate, Nehru had weighed in on his mentor’s side. On Gandhi’s insistence, Ambedkar was included in Nehru’s cabinet as the law minister. Here again, despite several ideological differences, Nehru and Ambedkar worked together in the Constituent Assembly until India adopted its Constitution in 1950. As Mani Shankar Aiyar writes, “The first test of the efficaciousness of the new Ambedkar-drafted Constitution for root-and-branch social reform came with the Hindu Code Bill, tabled in 1951.” Ambedkar was disenchanted with the Hindu dominated assembly and walked out of the cabinet in 1952. “Nehru, on the other hand, recognizing realistically and pragmatically his lack of influence as a religious skeptic on those who passionately upheld hallowed tradition, however cruel and unjust, believed his voice would count for much more in a legislature elected on the basis of full adult franchise, untrammeled by no social restrictions other than reservations for the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, which he welcomed.” The reformation of the Hindu code bill and other personal laws continues to be contentious in contemporary India, and one of those legacies wherein the Founding Fathers perhaps failed. Yet, history has been more kind to them than some of the right-wing propaganda in recent years has suggested.

Nehru was a religious skeptic, yet he respected religious freedom and believed strongly in keeping religion and the state separate. His main concerns were to advance India from a traditional to a modern day progressive nation. He said, “We are citizens of a great country, on the verge of bold advance, and we have to live up to that high standard. All of us, to whatever religion we may belong, are equally the children of India with equal rights, privileges and obligations. We cannot encourage communalism or narrow-mindedness, for no nation can be great whose people are narrow in thought or in action.” Nehru’s progressive ideology was what largely helped shape the modern Indian state, especially at a time when several leaders of the day were rooted in traditions and religious fundamentalism. His scientific and ethical attitude in public life were exemplary, and hold a mirror to politicians in contemporary India who are often divided on parochial ideologies.

Legacy

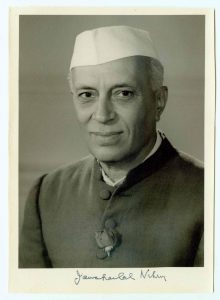

The silver-tongued Shashi Tharoor, writing on Nehru’s legacy, said that “For the first seventeen years of India’s independence, the paradox-ridden Jawaharlal Nehru—a moody, idealist intellectual who felt an almost mystical empathy with the toiling peasant masses; an aristocrat, accustomed to privilege, who had passionate socialist convictions; an Anglicized product of Harrow and Cambridge who spent almost ten years in British jails; an agnostic radical who became an unlikely protégé of the saintly Mahatma Gandhi—was India. Upon the Mahatma’s assassination, Nehru became the keeper of the national flame, the most visible embodiment of India’s struggle for freedom. Incorruptible, visionary, ecumenical, a politician above politics, Nehru’s stature was so great that the country he led seemed inconceivable without him. A year before his death a leading American journalist published a book entitled After Nehru, Who? The unspoken question around the world was: ‘after Nehru, what?’”

An India, without Nehru was once inconceivable. The destiny of the country, will continue to be guided by his ideals of a secular, democratic, republic—a sovereign nation-state, tempered by millennia of history and traditions. In shaping the contours of modern India, laying the foundation for democratic institutions and industrial economic growth, Nehru has played a most significant of roles. His upbringing and his years in Britain and Europe made him a global scholar, his immersion in the Indian freedom struggle in the shadow of Gandhi tautened him, but it was this self-made man that created history. It is his kind of leadership, moral courage, and indomitable faith in pluralism that the collective conscience of India bleeds for today.