BY JOELLE THOMAS

As the leaders of the world gather this week to discuss the climate, two dark clouds hang over the Paris skies. The first is the recent, palpable memory of terrorist attacks. The second is a more distant but tangible memory of a climate negotiation gone awry: Copenhagen.

When world leaders gathered for the 15th annual rendition of the Conference of Parties (COP) in Copenhagen, chaos ensued. Governed by the rules of the UN General Assembly, all of the world’s 195 states had to reach consensus on how to deal with climate change. But days of procedural posturing, secret draft agreements, clandestine side meetings and a hurling of harsh rhetoric deteriorated the negotiating process. And for a while, no one could find the Chinese delegation. Finally, heads of state swooped in at the 11th hour, locked themselves in a conference room and pulled together a semblance of an agreement to save face in front of the rest of the world.

Copenhagen is an example of international negotiations at their worst. And with a similar procedure, the same host of big personalities, and the underlying global commons problem, cynics argue that the ongoing Climate Conference in Paris (COP21) will be no different. At its core, the COP is a United Nations General Assembly meeting, and carries with it the strengths and weaknesses of a UN forum in its effort to propel the world to collective action.

In particular, skeptics have voiced four key weaknesses in the UNFCCC as a negotiating forum for climate change:

- An urgent global problem that requires commensurate action, climate change must be tackled by Heads of States, not junior negotiators.

- Climate change disproportionately affects the Global South and is driven by a handful of key emitters, yet it is debated in a setting where all the world’s countries are on equal footing.

- Climate agreements could prompt significant changes to the global economy, but they are drawn up in the absence of the carbon economy’s key drivers: energy companies, carbon-intensive businesses, and consumers.

- As a global commons problem, climate change—and the solutions to combat it—will be overseen without an enforcement mechanism.

But all these things are already happening this year in Paris. Following lessons from climate conferences of yore, COP21 has moved towards a more inclusive, binding, and optimized negotiations process to address each of these problems.

Problem 1: As a problem of global proportions, climate change must be tackled by Heads of States rather than junior negotiators.

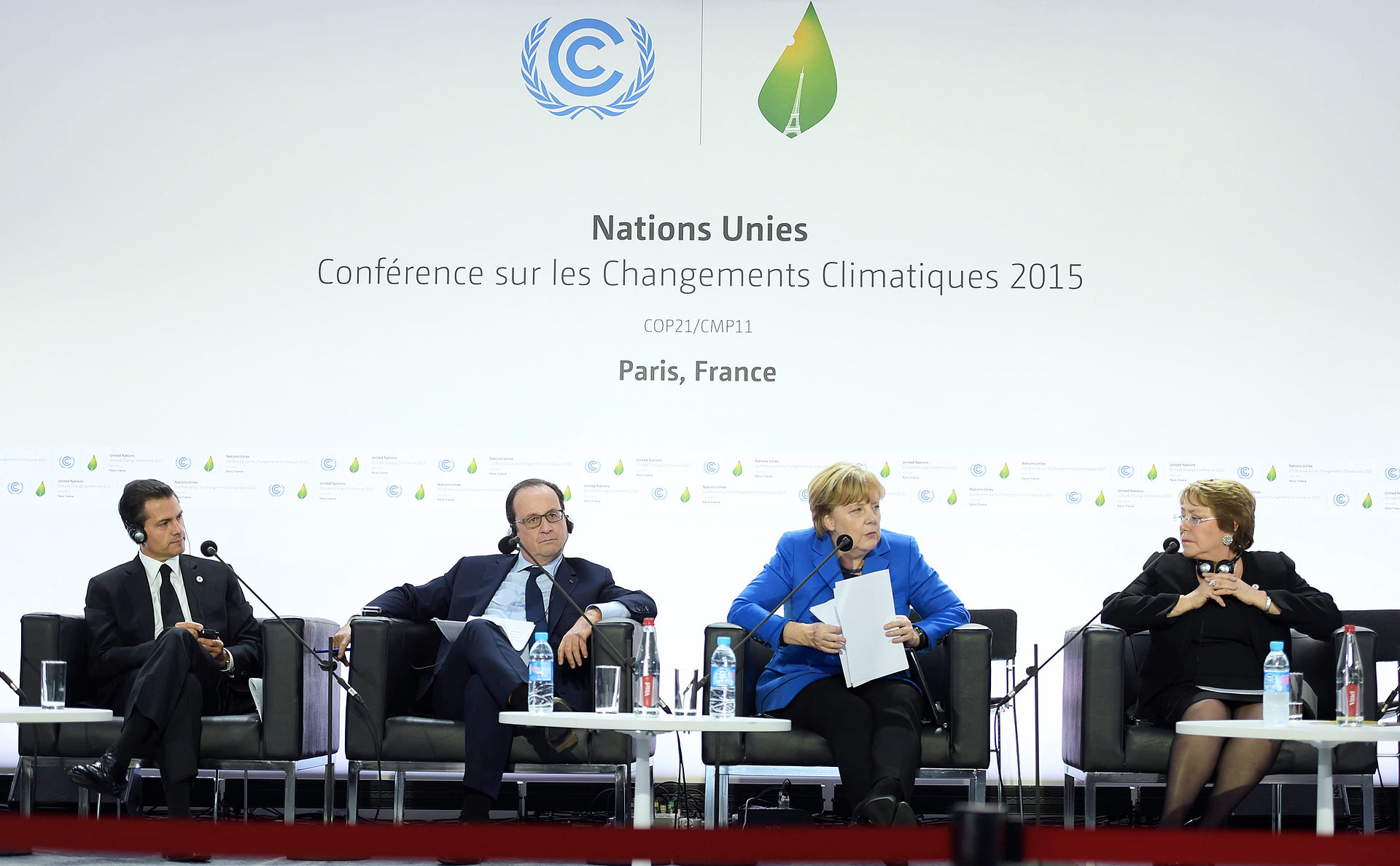

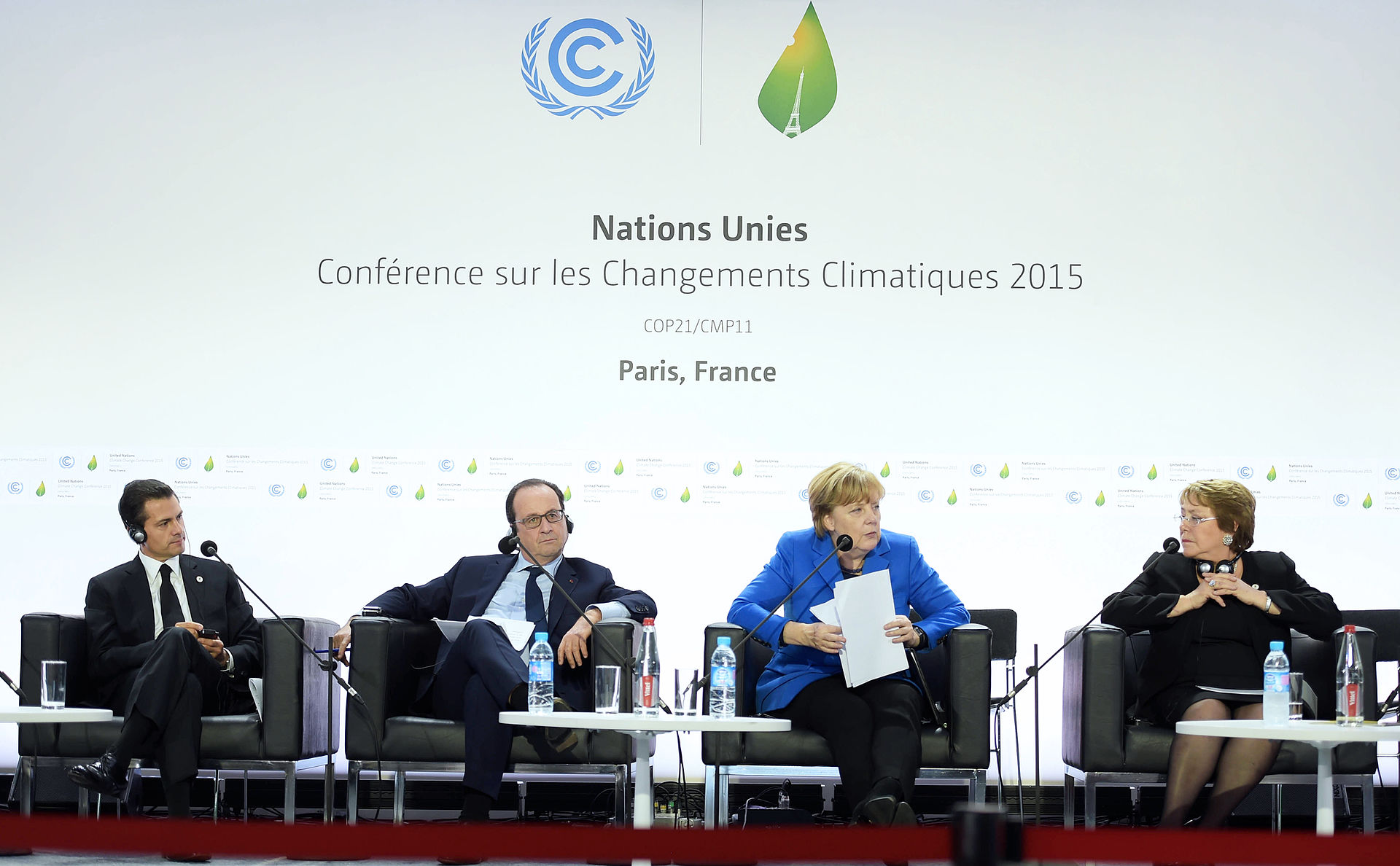

Response: Heads of State have—and often do—attend COPs. COP21’s cast of characters boasts over 120 Heads of State, including VIPs Presidents Obama, Putin, Xi Jinping, and Prime Ministers David Cameron and Angela Merkel.

Learning from the lessons of Copenhagen, COP21 is structured to optimize success. The office of Christiana Figueres, the head of UNFCCC, lobbied forcefully to schedule the summit of world leaders at the beginning of the COP21 negotiations. Structurally, this allows the leaders to agree to big-ticket issues, then give marching orders to their delegations to finalize the details. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius is so confident in this strategy that he has asked negotiators to agree to a final version of the negotiating text six days before the conference ends. This move adds to the already astronomical pressure on leaders to come to an agreement—and soon.

Problem 2: Climate change disproportionately affects developing countries and is driven by a handful of key emitters, but is debated in a setting where all 195 countries are on equal footing.

Response: The UN General Assembly is a rare but important opportunity to equalize the playing field in a world dominated by coalitions and great powers. It is imperative for underrepresented groups—most notably, Pacific islands who are at risk of disappearing from rising sea levels due to global warming—to have a platform to voice their own very legitimate concerns. A key issue for developing countries at the Paris negotiations will be financing, as many countries ask for reparations for the negative impacts of climate change on their territories and for financial assistance in developing a cleaner economy. Without a vote, these nations don’t stand a chance in asking for the tools they need to secure their future.

Equal airtime also does not mean that all countries must agree equally, or even proportionality, to cut emissions. COP21 is governed by the theory of “common but differentiated” contributions, whereby countries agree to reduce emissions, but at rates that are sustainable for their own economies. This “common but differentiated” philosophy is largely responsible for bringing many emitters from emerging markets to the table. “Why should I deprive myself of the chance to grow my industry when developed countries polluted the world?” they ask. Under COP21’s structure, they don’t have to. This strategy offers a zone of possible agreement—moving away from the all-or-nothing conversations that have undermined so many climate conferences in years past.

Problem 3: The solutions to climate change will transform the global economy, but key stakeholders—energy companies, carbon intensive businesses, and consumers—are not at the negotiating table

Response. While big business and civil society don’t have physical seats at the negotiating table, their voices are far from absent.

Following the cancellation of Paris’s climate rally, Place de la Republique—Paris’s historic square for public protest, is filled with the shoes of phantom marchers, as climate activists show their support in abstentia. The rest of the world is stepping in to fill these shoes, with 2,000 Climate Marches sweeping the world on November 29th. This movement is record-breaking, and it lends a voice to a civil society that is willing to make small sacrifices now to secure a better future. Most importantly, it is a demonstration of the possibilities of collective action—the very action required to bring down global emissions to sustainable levels. The very action that COP21 endorses.

Big Businesses, too, are part of the movement, making contributions and pledges to reduce emissions on a new feature on UNFCCC’s homepage. Some have been more outspoken than others on the importance of climate reductions, calling for businesses to abandon fossil fuel-intensive assets before they become stranded. More than 800 of the largest listed companies around the world favor a global deal to tackle climate change. Support from business is unprecedented, and as divestment from fossil fuels continues to grow, their influence on the fossil fuel industry will too.

Lastly, civil society and the private sector are structurally incorporated into the COP21 fanfare through an elaborate series of side events. Organized by NGOs registered under UNFCCC alongside private sector players, these side events are exhaustive; more than 600 conferences and debates will take place at COP21’s Le Bourget site and are open to the public; when accounting for events that require accreditation, this number reaches the thousands.

Problem 4: Climate change is a global commons problem, but the UN oversees it without an enforcement mechanism.

Response. UN General Assembly Conventions are non-binding and unenforceable. There are few options to create a binding, international agreement to which all the countries of the world are privy.

Instead, COP21 could offer the next best option. This week, negotiators will seek to establish a process through which countries must report on their progress towards achieving their emissions reductions contributions. With a view to promote transparency in the absence of binding accountability, this process could be very powerful for putting pressure on countries to make a good faith effort to keep to their targets. In a recent talk in at the Kennedy School, New York Times reporter Coral Davenport remarked that if countries were meant to report on their progress every 5 years, they would be much more inclined to follow through with their contributions for fear of shaming in front of their peers.

Given the global scale of climate change, the necessity to engage diverse stakeholders, and the absence of enforceable mechanisms, there is no guarantee that Paris will not derail into another Copenhagen. But despite these dark clouds, the leaders of the world have sent the clearest signal that they have faith in this negotiating process—they are staying the course. Following the terrorist attacks on Paris earlier this month, not a single world leader cancelled their attendance at the climate conference, even as security threats mounted.

If climate negotiators are all-in, they must be ready to see it through.

Photo via Wikimedia.