As governments around the world fight tooth and nail to expand COVID-19 vaccinations, another vaccination drive is taking place in the background. Since 2014, the Singapore government has strongly recommended the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for girls aged 9-14 years old.[i] The virus, which can be transmitted through vaginal, anal, and oral sex with an infected individual, causes more than 95% of cervical cancer cases worldwide.[ii] Cervical cancer is the tenth most common cancer and the eighth most frequent cause of death among women in Singapore.[iii]

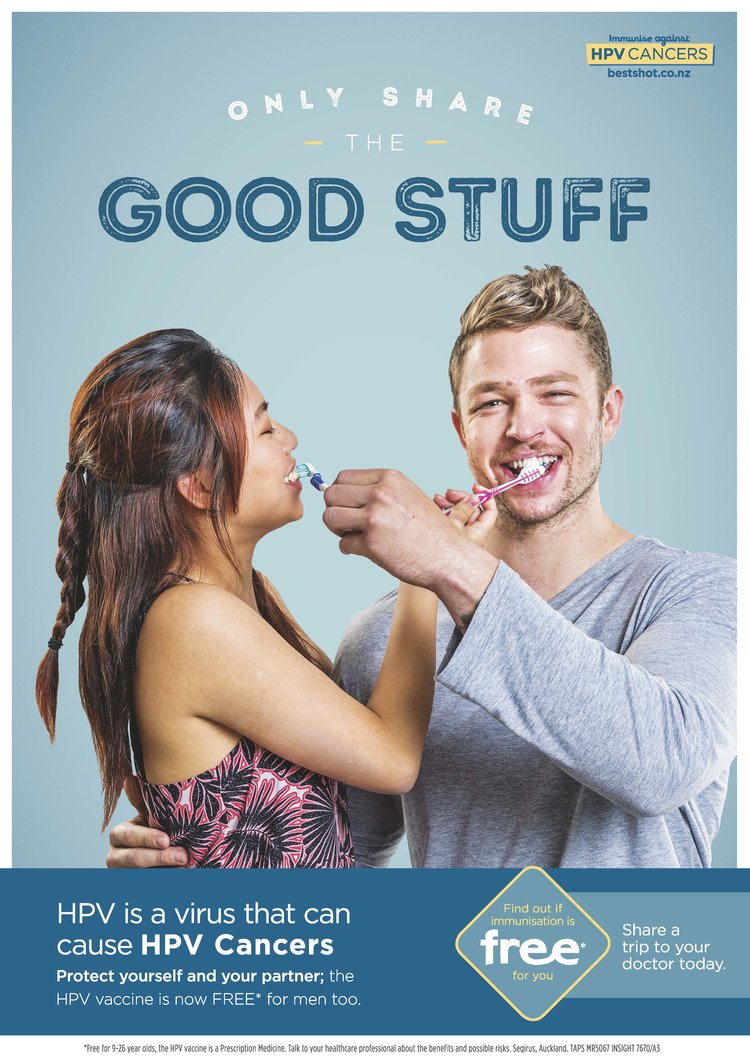

Consequently, government efforts to promote HPV vaccination have tended to focus on women. Advertisements promoting the inoculation therefore actively target a female audience as part of a strategy of targeted communication towards women. Such strategies are not limited to Singapore—advertisements promoting HPV vaccine Gardasil in the US have framed it as a “gendered” vaccine through its “exclusive focus on women and their bodies.”[iv] This was in part because the vaccine was initially approved for women only before subsequently being approved for men too.[v]

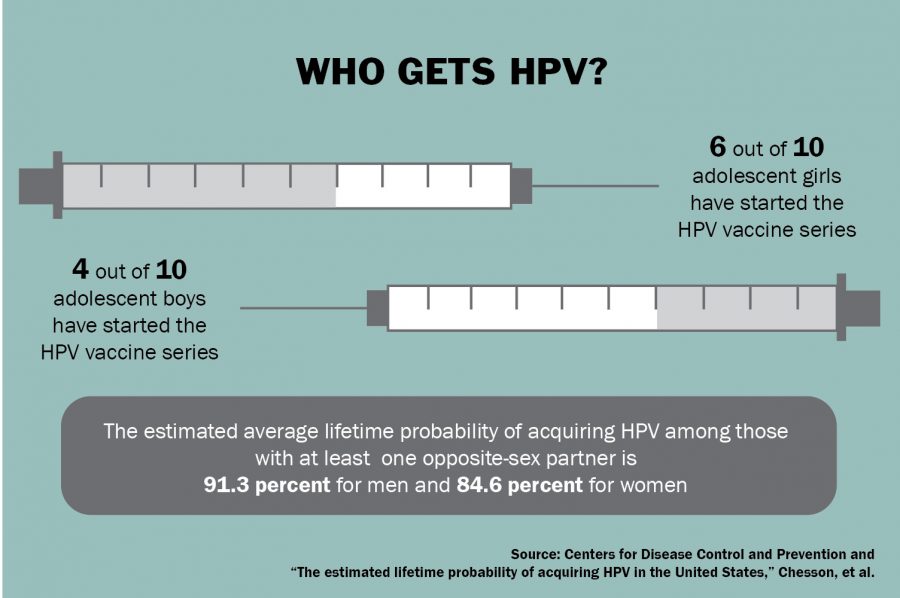

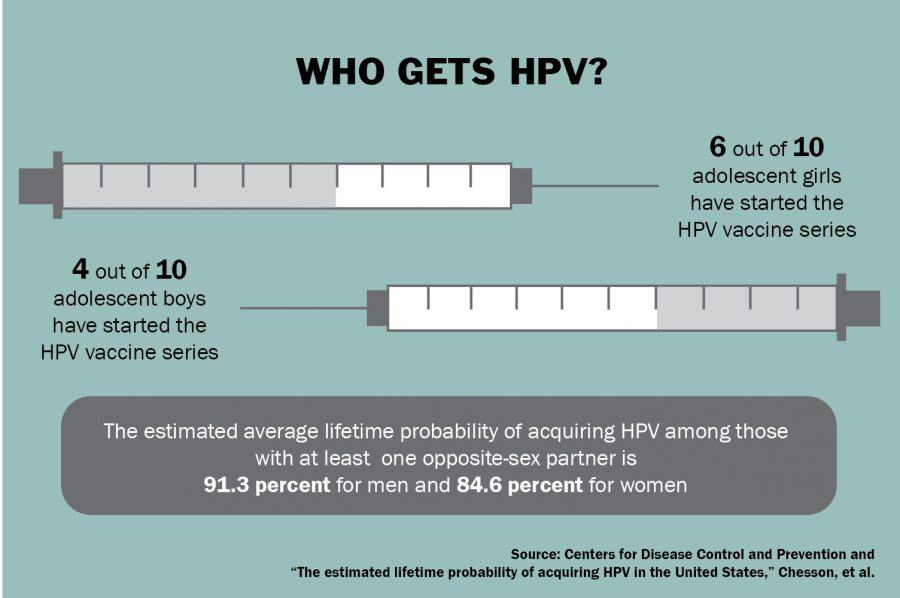

Unfortunately, this sort of targeted advertising creates the possible misperception that HPV is a disease that only affects women, or that the vaccine is suitable only for women. In fact, HPV affects men too. The virus is also a “cause of important disease ranging from genital warts to several cancers of anogenital and aerodigestive tracts” in men.[vi] Around 6 in 10 of all penile cancer cases in the UK are caused by HPV.[vii] There is currently no available test for HPV cancers in males.[viii]

While the occurrence of HPV-related cancers is relatively rarer in men than in women, vaccinating men against HPV can help better protect women from the virus.[ix] Men can serve as “reservoirs” for the virus and spread it to their sexual partners.[x] Given that the economic burden associated with treating cervical cancer in Singapore runs up to S$57.6 million over 25 years starting in 2008, the cost savings alone provide a compelling economic rationale for vaccinating men in Singapore.[xi]

Already, governments worldwide are taking steps to promote male HPV vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US recommends that all preteens (including boys and girls) aged 11 or 12 should get the HPV vaccine, as well as everyone through age 26 years if not vaccinated already.[xii] The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) routinely offers the vaccine to both boys and girls aged 12-13 when they are in Year 8 of school, with the second dose offered 6 to 24 months later. [xiii]

Currently, however, the Health Promotion Board in Singapore only “strongly recommend[s]” the HPV vaccine for females aged 9 to 26, though it notes that it is also available to males of the same age [xiv]. HPV vaccination is also only included in the National Childhood Immunisation Schedule (NCIS) for girls and not boys.[xv] Since 2019, all Secondary 1 girls have been able to choose to take the vaccine for free, but the same option is not available to boys.[xvi]

“We cannot protect men by protecting only women … Men must also get that protection,” says Professor Roy Chan, president of Action for AIDS and a specialist in sexually transmitted infections in a report by The Straits Times.[xvii] The same report notes that a local group started in March 2021, “Alliance for Active Action Against HPV,” has been working to engage with men to raise awareness about HPV and how it affects them.[xviii]

To be sure, the emphasis on female vaccination may reflect policy priorities, since the vaccination of women might be accorded higher priority given the limited vaccine supply. Yet, studies in the US and France find that gender-neutral vaccination is more cost-effective vis-à-vis girls-only vaccination.[xix] Concentrating only on female vaccination to target cervical cancer may also be less effective in preventing other forms of cancer caused by HPV.[xx]

It is therefore important for policymakers to change the narrative that HPV is a “women’s disease” that only affects women. A sad reality of androcentric society is that men are punished more harshly for transgressing gender roles than women who do the same.[xxi] Therefore, the implicit framing of HPV as a feminine disease and HPV vaccines as a “female” vaccine may make men less likely to want to engage with the role HPV plays in their own lives or get vaccinated.[xxii]

Singapore’s public health strategy should therefore emphasize HPV as a disease that affects the entire population instead of a single sex. The Health Promotion Board should consider following the lead of other developed countries by recommending and equalizing access to HPV vaccines for boys as well as girls by making it free for both sexes where financially prudent. Such policies have already been implemented in the UK, whose Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunity have deemed such a move to be cost-effective.[xxiii]

To be sure, it may take time before free HPV vaccinations for all sexes can be rolled out. Not only has a HPV vaccine shortage – expected to last till 2023-2025 – caused the WHO and many governments worldwide to prioritize female vaccination, there may be some lag time before multi-year contracts with manufacturers can be re-negotiated. [xxiv] Yet this lead time creates an opportunity for governments to slowly change the gendered discourse surrounding HPV vaccines before an expansion of vaccination efforts.

Ultimately, HPV is a scourge that affects all sexes, while the HPV vaccine is a universally efficacious preventive measure against it. The more people get vaccinated, the higher chance Singapore and the international community will have of winning the war against this carcinogen. Society’s gendered view of HPV should not be allowed to be an obstacle to victory.

[i] Sun Kuie Tay et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Two-Dose Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Singapore,” Singapore Medical Journal 59, no. 7 (July 2018): 370–82, https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017085.

[ii] “Cervical Cancer,” accessed April 30, 2022, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer.

[iii] Tay et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Two-Dose Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Singapore.”

[iv] Maura Pisciotta, “Gendering Gardasil: Framing Gender and Sexuality in Media Representations of the HPV Vaccine,” Dissertations and Theses, January 1, 2012, https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.807.

[v] Pisciotta.

[vi] P. CANEPA et al., “HPV Related Diseases in Males: A Heavy Vaccine-Preventable Burden,” Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene 54, no. 2 (June 2013): 61–70.

[vii] “Risks and Causes | Penile Cancer | Cancer Research UK,” accessed April 30, 2022, https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/penile-cancer/risks-causes.

[viii] “5 Reasons Boys and Young Men Need the HPV Vaccine, Too | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center,” Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, June 10, 2021, https://www.mskcc.org/news/5-reasons-boys-and-young-men-need-hpv-vaccine-too.

[ix] Kathleen Doheny, “HPV Infection in Men,” WebMD, January 22, 2022, https://www.webmd.com/sexual-conditions/hpv-genital-warts/hpv-virus-men.

[x] Miller, “Should Men Get the HPV Vaccine?,” Verywell Health, November 13, 2020, https://www.verywellhealth.com/should-men-get-the-hpv-vaccine-5087312.

[xi] Tay et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Two-Dose Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Singapore.”

[xii] “STD Facts – HPV and Men,” Center for Disease Control (CDC), April 18, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv-and-men.htm.

[xiii] “Who Should Have the HPV Vaccine? – NHS,” nhs.uk, July 31, 2019, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/who-should-have-hpv-vaccine/.

[xiv]“Preventing HPV Infection: HPV Vaccination,” Health Hub, accessed May 1, 2022, https://www.healthhub.sg/a-z/diseases-and-conditions/701/faqs-on-hpv-and-hpv-immunisation.

[xv]“Preventing HPV Infection.”

[xvi]Linette Lai, “Group Aims to Raise Awareness of HPV in S’pore, Hopes Men Get Same Access to Vaccine as Women,” The Straits Times, December 19, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/local-group-raises-awareness-of-hpv-in-spore-hopes-boys-will-have-same-access-to-vaccines-as-girls.

[xvii] Lai.

[xviii] Lai.

[xix] Anna R. Giuliano and Daniel Salmon, “The Case for a Gender-Neutral (Universal) Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Policy in the United States: Point,” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 17, no. 4 (April 8, 2008): 805–8, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0741; Laureen Majed et al., “Public Health Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of a Nine-Valent Gender-Neutral HPV Vaccination Program in France,” Vaccine 39, no. 2 (January 8, 2021): 438–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.089.

[xx] Giuliano and Salmon, “The Case for a Gender-Neutral (Universal) Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Policy in the United States.”

[xxi] Selcuk Sirin, Donald McCreary, and James Mahalik, “Differential Reactions to Men and Women’s Gender Role Transgressions: Perceptions of Social Status, Sexual Orientation, and Value Dissimilarity,” The Journal of Men’s Studies 12 (December 1, 2004): 119–32, https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1202.119.

[xxii]Ellen M. Daley et al., “The Feminization of HPV: Reversing Gender Biases in US Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Policy,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 6 (June 2016): 983–84, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303122.

[xxiii] “HPV Vaccine to Be Offered to All Children in England, Not Just Girls,” New Scientist, accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.newscientist.com/article/2174940-hpv-vaccine-to-be-offered-to-all-children-in-england-not-just-girls/.

[xxiv] “IPVS Statement on Temporary HPV Vaccine Shortage. Implications Globally to Achieve Equity,” accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.hpvworld.com/articles/ipvs-statement-on-temporary-hpv-vaccine-shortage-implications-globally-to-achieve-equity/.