Several weeks ago, the two of us wrote an op-ed outlining the major challenges facing the United States’ contact tracing programs. We issued an urgent call to action for federal leaders to step up, develop a unified strategy, and provide critical life support to these programs. Federal leadership on contact tracing is paramount to the nation’s ability to gain control of this virus until life-saving therapies or a vaccine are made widely available, but state leaders have a role to play in addressing many of the challenges we outlined. Here, we will reintroduce some of the challenges we outlined in our previous piece and dive deeper into what states can do to tackle them.

Slow/Bureaucratic Procurement Processes

Since the outset of the pandemic, public health leaders have called for at least 100,000 contact tracers to keep up with the spread of the coronavirus. As of now, the nation has less than half of that. Part of the challenge in each state’s ability to scale the contact tracing workforce has been a set of slow, bureaucratic procurement processes hamstringing agencies’ ability to select vendors to work with.

To break down these bureaucratic channels, Governor Newsom in California declared a state of emergency. This declaration gave state agencies permission to cut through their normal red tape and enabled procurement for contact tracing to move more quickly. California’s Department of General Services released a guide outlining how departments could use the emergency order to speed their procurement efforts, including using leveraged procurement agreements, allowing awards to be made with the approval only of the agency head (without Office of Legal Services approval), and encouraging the use of purchasing cards and e-signatures. California now employs over 10,000 contact tracers and plans to hire at least 17,000. Other states can consider utilizing similar procurement tactics to help move the process along in a timelier manner.

Workforce Management and Retention

Staff turnover has plagued contact tracing programs across the nation, hampering the ability to further scale the workforce and keep up with the spread of the virus. Some people have applied to work as contact tracers without fully understanding the emotionally and physically draining nature of the job. As they call person after person, dealing with the struggles of individual Americans and their families, it takes a toll on contact tracers’ emotional well-being. Many understandably decide to leave the role after a short amount of time, not only due to the stress, but also because they feel unsupported by the programs they work for.

This is why it is critical that contact tracing programs prioritize hiring individuals with public health and/or social work backgrounds. These experienced workers already have the training and cultural understanding to deal with very sensitive issues and sometimes hostile people. We know from personal experience that there is certainly no shortage of available trained workers across the country, and more must be done to identify and onboard them, rather than simply picking those with the bare minimum qualifications just to fill these positions faster. While it is important to scale the workforce quickly, hiring for speed without ensuring quality dooms a contact tracing program to struggle with retention. And low retention leads to operational delays that waste the time gained by hiring underprepared workers.

Part of the issue stems from procurement teams prioritizing the fastest and cheapest staffing solutions, leading to contracts with some large staffing firms that appear to have placed the first candidates they could find that met the absolute minimum qualifications. To combat this, agencies should be intentional about working with staffing vendors that are focused on public health, and that demonstrate an understanding of contact tracing, and fast and efficient operations. Massachusetts, which has been held up as an example of contact tracing success, contracted Partners in Health — an organization with a long history in both public health and contact tracing — to operate their contact tracing programs.

Additionally, compassion fatigue, or emotional exhaustion that comes from caring for others in distress, appears to be weakening workforce retention. There is no research yet on contact tracing and compassion fatigue in the age of COVID, but we are seeing regular eyewitness reports of contact tracers leaving the job because the emotional toll is too high. Contact tracing programs that don’t have policies and support structures in place to protect the mental health of their workforce are likely to see retention issues around compassion fatigue as the pandemic wears on. In Texas, contact tracers are required to take a compassion fatigue training course and in California, a psychologist works with contact tracers to help them cope with the compassion fatigue they may be experiencing.

Inconsistent Messaging

To this day, we continue to see inconsistent messaging coming from elected leaders and public health experts across local, state and federal government. With citizens hearing different and often conflicting messages coming at different times, from different people, they are understandably left confused about public health guidelines and contact tracing. This also makes it difficult for contact tracers to effectively communicate with and gain the trust of those they call.

Governments can improve their clarity in messaging by first ensuring that state and local leaders are communicating the same messages, and that funding is allotted to ensure that a uniform message is communicated across all platforms, from public signage to local news to social media.

Considering the tight timeframe and urgency of Covid-19, agencies should consider working with external communications vendors capable of quickly targeting the right demographics with the right messaging. For example, these communications contractors could be experienced in using targeted social media messaging to communicate with younger generations or to develop public messaging for the multitude of languages that US residents speak.

State & county public health departments should also partner with their local governments and local business associations, such as chambers of commerce or business improvement districts, to develop a proactive, comprehensive distribution system for messaging and signage in public spaces, stores and restaurants. Like the signs we see on the road, the more consistent the message and delivery, the more likely the public will be to recognize, understand and trust the message.

We recognize that without federal standards for messaging (beyond optional CDC communications tools) or signage, ensuring uniform communications and then coordinating these efforts across a state can be challenging. Therefore, it is critical that states dedicate a single agency, collaborative, or individual to champion these efforts. Think of Dr. Anthony Fauci, but on the state level.

Privacy Concerns

Adding to the complexity of executing an effective contact tracing program is the lack of uniform standards for protecting individual health information. There are no federal data privacy laws in the United States, and some states such as California and New York have taken it upon themselves to pass their own data privacy laws. Add HIPAA privacy rules and regulations to the mix, and together these laws have created a patchwork of conflicting rules and regulations that make it difficult for public health leaders to know what is acceptable and what is not when it comes to contact tracing, especially when using digital contact tracing apps. This confusion has extended to the public, where many people still perceive contact tracing only as an app on their phones tracking their every move. Local governments attempted to institute a variety of contact tracing apps, but adoption failed to reach the level necessary for the apps to be effective, and apps faded from the conversation. However, with colleges recently debuting their own contact tracing apps as students head back to campus (or at least attempt to), the resulting privacy issues are once again in the spotlight.

In the absence of uniform data law or standards, states can take a lead role in combating privacy concerns. They can do so by prioritizing data privacy as a key standard in selecting vendors to manage the contact tracing workforce as well. The National Institutes of Health have also helped demonstrate how to build data privacy into contact tracing apps and programs.

More than prioritizing data privacy in vendor selection, it is also important to communicate this priority to the public. It is not enough to simply choose a vendor that takes privacy seriously, it is even more important that the public know that their individual privacy is of utmost importance to their local, county or state government, as much as it is their priority to suppress the virus. More than paying lip service to data privacy, it is vital that state, county, and local health departments work with selected vendors to demonstrate to the public that privacy protection is a top priority.

Moving Forward

Unfortunately, the timeline for developing life-saving therapies and vaccines is unclear, and it could potentially be years before we have something that proves effective at scale. In the meantime, testing and contact tracing, regardless of the challenges associated with their execution, are the most effective tools available to public health departments to help control the spread of Covid-19. In the absence of a national testing and contact-tracing strategy, local, county and state leaders must work to streamline procurement, prioritize hiring individuals with public health backgrounds, provide mental health support to contract tracers, align messaging and communication across all levels of government, and publicly prioritize data privacy. State leaders have an essential role to play in driving these critical actions forward. It is their role to ensure the success of contact tracing both in their jurisdiction and throughout the country – doing so is paramount to protecting public health.

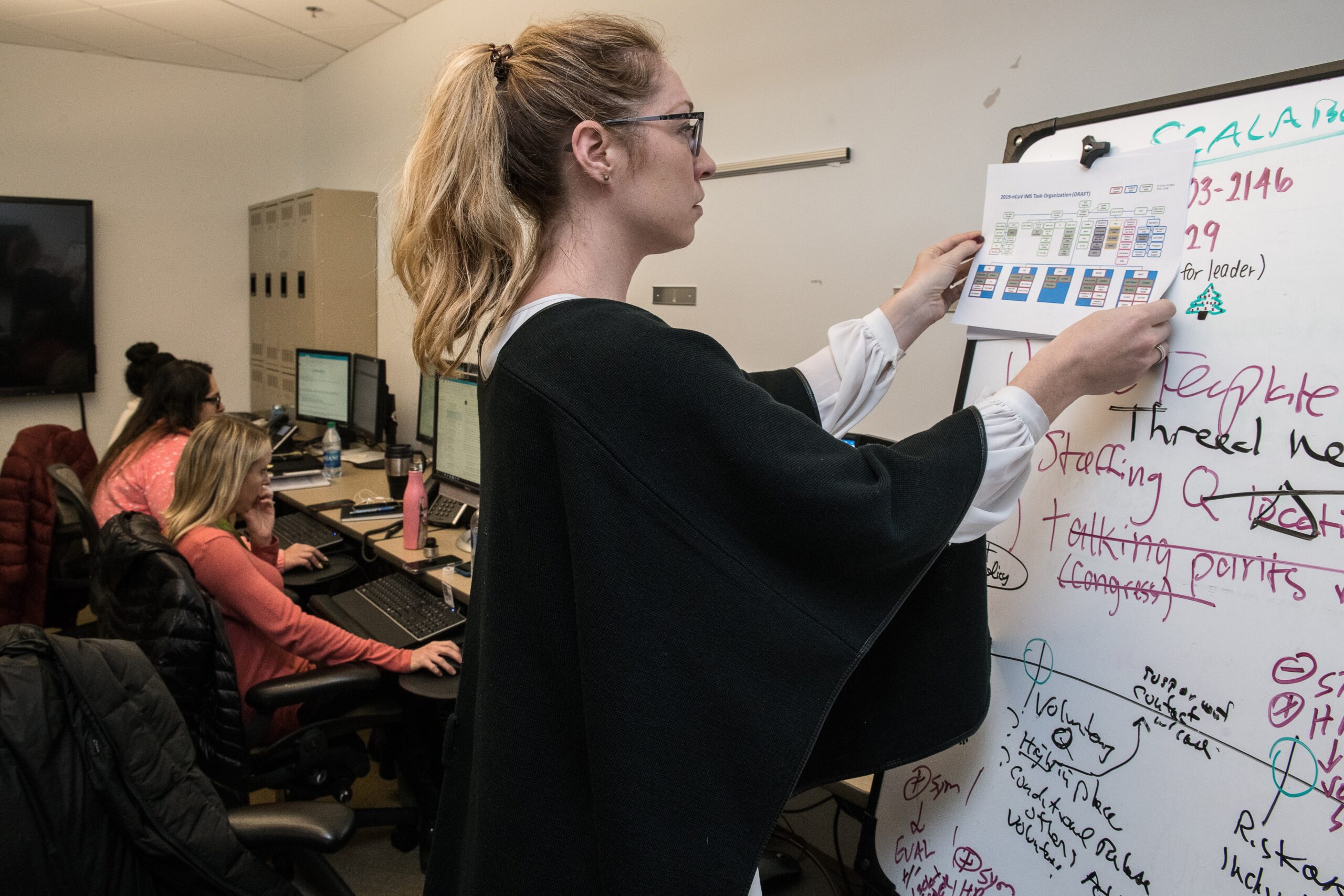

Photo by: CDC