BY KEVIN FRAZIER

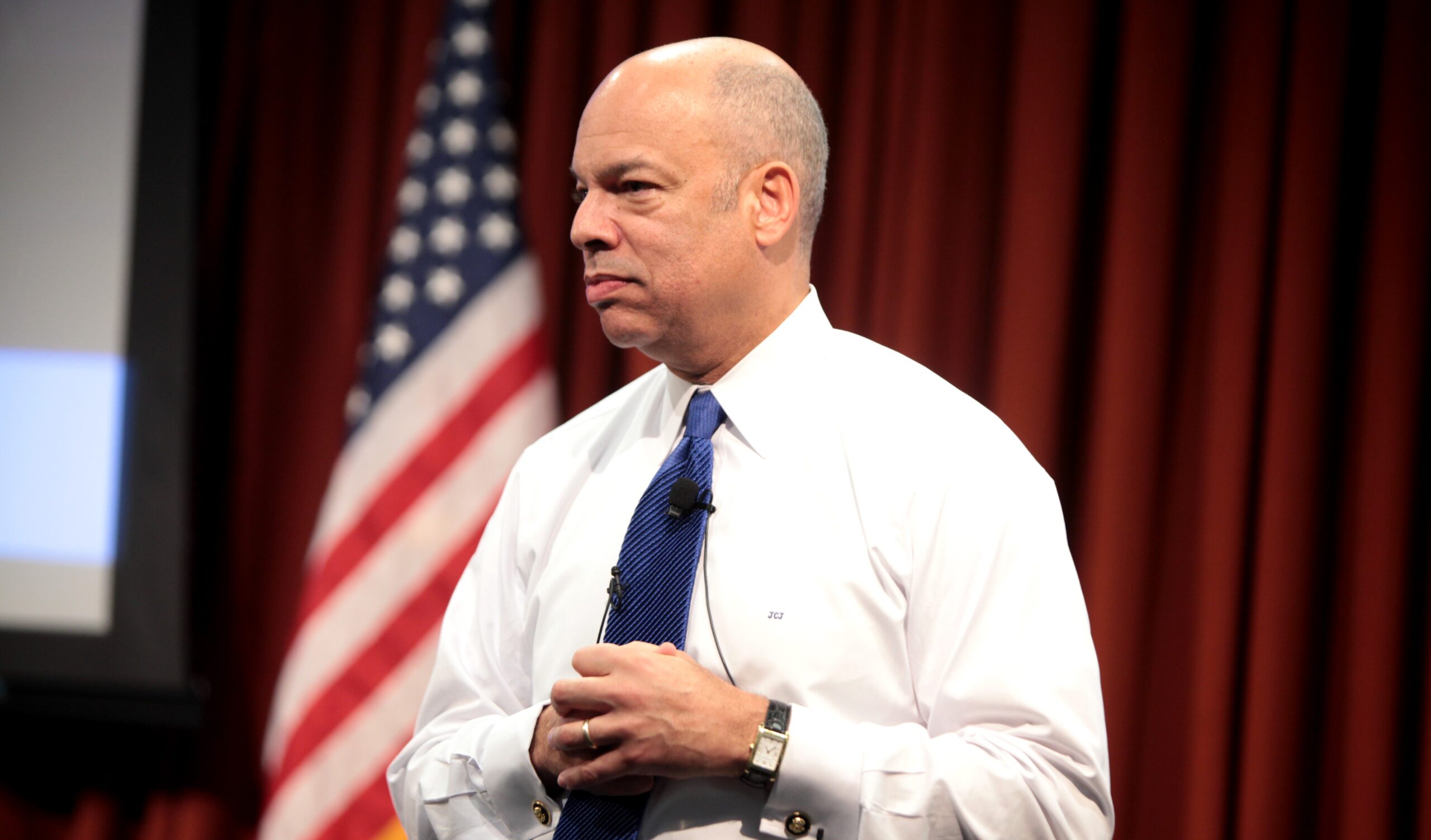

Distrust in the federal government pervades the United States. Its ubiquity threatens the stability of institutions and their capacity to govern. That’s why I recently sat down with Jeh Johnson. As General Counsel of the Department of Defense and, later, Secretary of Homeland Security under the Obama Administration, former Secretary Johnson established a reputation for transparency and accessibility. He’s perhaps best remembered for his ability to eloquently explain the Obama Administration’s counterterrorism policies, as he did in 2012 in a well-received speech at Oxford Union. Given Secretary Johnson’s reputation for candor, I focused our conversation on how he thinks students at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University can help restore trust in government.

The Secretary’s answer? Restoring trust requires encouraging public participation and increasing official accountability.

A basic example of this relationship between participation, accountability, and trust, Secretary Johnson told me, plays out in schools. Every year, many fourth graders are tasked with writing a note to a public servant. It’s an exercise, Secretary Johnson explained, that creates trust in government. The public servant receives the letter and writes back, establishing an important pattern: If you engage, your elected officials will listen and respond. In Secretary Johnson’s view, however, that pattern is nonexistent for many Americans. The resulting distrust is, to quote the Secretary, “disheartening.”

Secretary Johnson’s trust in the government also began during his childhood. Regular interaction with family members who worked for the federal government introduced him to civic engagement and gave him a positive perception of the government.

“Not enough Americans have the opportunity to appreciate all the good the government does and all the dedication and hard work that goes into serving the public,” Secretary Johnson said.

Employment data backs up the Secretary’s theory. In 2015, the percentage of Americans employed by the federal government dropped to its lowest percentage since the 1960s. If, as Secretary Johnson argued, contact with federal government officials is instrumental in establishing trust, then the slow growth of the federal workforce could explain some of the decreased public faith in government. I would support efforts to test this idea further. Overall the proportion of the population employed by the government—including local, state, and federal offices—varies substantially by state. This variation presents researchers with a chance to see just how correlated trust is with the government employee contact.

While in office, Secretary Johnson reported that he strived to make his own interactions with the public positive; he believed doing so could spark greater citizen participation.

“I was transparent,” Secretary Johnson emphasized. “I was visible.”

Secretary Johnson also tried to adhere to practices of government accountability. He cited actions he took in response to public concerns around then-President Barack Obama’s counterterrorism policies.

“When I was General Counsel of the Department of Defense I made a number of speeches about the legal architecture for our counterterrorism efforts,” the Secretary recalled, “to explain, not just to the lawfare crowd, but to the public in general how we were construing the laws.”

But are speeches sufficient to help Americans establish a pattern of engagement that results in trust and promotes accountability? I am not sure. The Obama administration’s use of the bully pulpit on counterterrorism issues might have made the public more comfortable with prioritizing national security over civil liberities.

So how do these concepts of participation and accountability play out in the 21st century context? Social media, Secretary Johnson asserted, has played this same role in the digital sphere—a digital bully pulpit, so to speak, that connects constituents and elected officials in a new way. Secretary Johnson added that social media presents a digital avenue for congressmen and congresswomen to get work done in D.C and connect with their constituents. For example, social media could be a medium through which citizens could find public service announcements that could help them get engaged in the government’s work. This sort of encouragement, the Secretary insisted, can go a long way in spurring the public to be more inclined to participate in civic affairs.

Social media is far from sufficient for reviving participation, reestablishing accountability, and restoring trust, Secretary Johnson qualified. But, he added, there are other ways of achieving these ends.

His first suggestion hinged on changing the goals of policymaking. Currently, the Secretary argued, politics is the end and not the mean. He attributed legislative inaction—a failure to respond to public engagement—to this shift in focus. Redirecting legislators’ energy toward problem solving can mend the break in the engagement-accountability pattern.

A step forward on this goal—the Secretary’s second suggestion—might start by encouraging congeniality among officials. Secretary Johnson remembered that his role model, one-time employer, Congressman Hamilton Fish IV willingly spent time in Washington, D.C. Comparatively, “members now only stay in Washington, D.C. maybe two or three days a week,” Secretary Johnson said. This lack of camaraderie, he added, contributes to officials merely playing to their political bases.

Prominent political scientists agree with Secretary Johnson. Norman Ornstein has touted the importance of representatives and senators socializing to establish a more congenial and productive congressional atmosphere. He argues that “parties” may reduce the influence of political parties. It follows that participation and accountability depend on two relationships: constituent with official and official with official.

The Secretary echoed this sentiment. Governing, he maintained, is about relationships. So, it’s no surprise that our one-on-one convinced me that the public has the chance to make the first move at reconciliation following the midterms. It’s now on all of us to ensure the newly elected officials and incumbents listen and respond. If the Secretary’s theory holds, engagement will spur accountability, jumpstarting a virtuous cycle of trust-based governance.

Kevin Frazier is a Master in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School and a JD candidate at the University of California-Berkeley. Originally from Oregon, Kevin previously worked for Governor Kate Brown and Google. His articles on inter-generational inequality and the convergence of technology and democracy have appeared in the Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, and Taipei Times.

Edited by Maggie Kadifa

Photo by Gage Skidmore