By Brian Monahan, MPA 2018

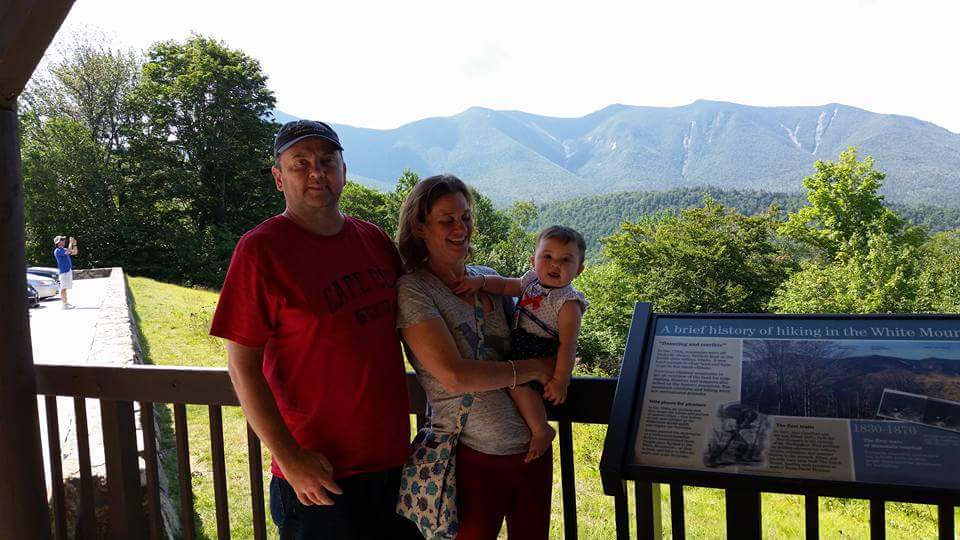

Commencement day I will be wearing the “Donate Life” logo of the New England Organ Bank to promote awareness of the need for more organ donations. When I arrived at the Kennedy School with a successful kidney transplant of 20 years, I never imagined that I would be searching for a new living donor to replace my failing kidney. But lessons learned in my Behavioral Economics and Market Design classes, have taught me that the challenge I now face is not insurmountable. Our school’s namesake, John Kennedy, once said that “every person can make a difference and every person should try.” My hope for myself is more time to watch my two young daughters, ages 3 and 2, grow up, but also to get the word out to policymakers of the future about what they can do to make a difference in the lives of the thousands of people awaiting lifesaving transplants. In that spirit, I have prepared this brief policymaker’s guide to organ allocation policy.

According to the National Kidney Foundation website, there are currently 121,678 people waiting for lifesaving organ transplants in the United States. Of these, 100,791 await kidney transplants (as of 1/11/16). The median wait time for an individual’s first kidney transplant is 3.6 years and can vary depending on health, compatibility, and availability of organs. Thirteen people die each day while waiting for a life-saving kidney transplant.

Recent Nobel Prize recipient Richard H. Thaler and Cass Sunstein, a Harvard Law School professor, wrote the 2008 groundbreaking book Nudge, which argues that in many policy areas where public participation is both critical and beneficial, governments “should make participation the default option. People are free to opt out, but inertia is on the side of the preferred outcome.” In the case of organ allocation, the preferred option from a public policy standpoint would be greater participation in the organ donor registry. For market designers, the key takeaway from Thaler’s work is that in designing markets to be most efficient, we must be cognizant of the fact that the human beings participating in the market do not always act rationally – but just as important, irrational behaviors can be anticipated and modeled.

While the United States has led the way in healthcare innovation, it continues to lag behind other advanced economies in its efforts to promote the societal good of organ donation. In particular, the supply of available organs for donation is low in the United States compared to other advanced economies. The United States should reconsider its default option, but also do what it can to promote a greater awareness of the need for organ and tissue donation and encourage members of the general population to consider a donation as an option.

Given the long wait for a transplant, for many people, such as myself, living donation is the only option. At this year’s commencement, I hope to do my part to spread the word about the need for new donors, and I hope other students will join me. Those interested in becoming livings donors can express their interest by going to www.MGHlivingdonors.org.