BY MAGGIE SALINGER

The morning seemed like any other in the Rhode Island State House until my team received a chilling email. It was a note from a local father, whom I’ll call John, still reeling from the loss of his son. Days before his son died of an opioid overdose, John had dragged him to a nearby treatment center. Although John desperately sought help, his son was not interested. As a result, the two of them were turned away. John felt he must reach out to the Governor’s Office to prevent other families from experiencing a similar tragedy. There was no clear directive in his plea, but we all shared enough of his pain to know what John was suggesting: legislation that would allow involuntary commitment for opioid use disorder. It might have saved his son’s life.

At the time, I was a student in medicine and public policy serving in Governor Raimondo’s office as a Dukakis Fellow. My work centered on opioids, the most pressing public health problem of our time. Each year, the epidemic takes more loved ones from us than car accidents do. It brings a child with neonatal abstinence syndrome into the world every 25 minutes. It spans all sectors of society and touches all corners of our communities.

Rhode Island has been among the hardest hit states. With a population barely over 1 million, we were still recording six lethal overdoses per week. This made my colleagues and me all the more motivated to develop solutions to the crisis. Our aim was to address every facet of addiction from prevention to recovery. As a part of our strategy, we had considered policies in line with John’s urge for involuntary commitment.

Involuntary commitment has been a mainstay of psychiatric care since the field’s inception, but the practice never ceased to be controversial. It is an intervention that places patients into treatment against their will, with or without court orders for varying lengths of time, depending on the circumstance. While the process and duration of involuntary treatment may differ by setting, the ethical concern of restricting personal liberty is central in all its contexts.

From a medical perspective, the principles that guide opioid-related policies are beneficence and non-maleficence. State governments share this perspective but call it parens patriae. Together, these principles direct us to ‘do no harm’ and ‘do what is best for the individual.’ States have the additional authority to exercise something called ‘police power,’ which allows them to restrict individual rights to protect the interests of the broader population.

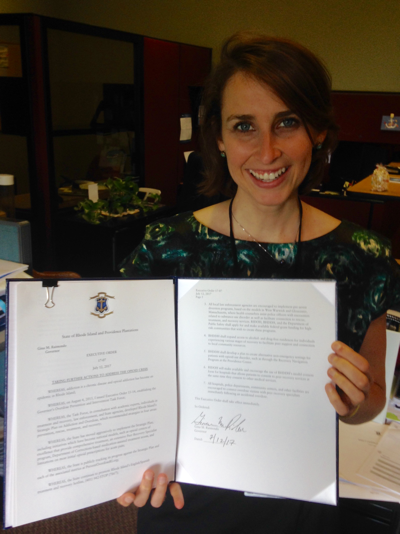

Photo: July 12th, 2017 – Governor Gina M Raimondo signing a new Opioid Executive Order.

Determining how to apply this ethical framework can be a challenge. In cases of florid psychosis where patients appear dangerous to self or others, we rely on involuntary commitment without reservation. We do so because we believe that initiation of inpatient treatment, even if it is involuntary, will serve to restore patient autonomy while also protecting society from harm.

In cases of substance use disorder, we fall short of such clarity. The clinical presentation of addiction does not typically demonstrate dangerousness or grossly impaired reality testing in the way psychosis, mania, or suicidality does. For that reason, patients with substance use disorders are rarely admitted to treatment against their wills, even in states where it is technically legal to do so.

When John’s anguished message arrived, the Rhode Island legislature had just rejected an involuntary commitment law for opioid use disorder. Despite the state’s leadership status in addressing the epidemic, this was an occasion where we had decided to examine the effects of other states’ programs before adopting our own.

I was the one who had outlined a list of pros and cons for the bill when it was under review by our office. I was also the one who was asked to draft a reply to John.

Finding the right response to his email was not easy. It struck me that, a month earlier, in the exact moment I had been preparing that legislative memo about involuntary commitment, there were probably families like John’s who were leaving treatment centers with an overwhelming sense of defeat and fear.

I stared at my computer in silence, hands frozen on the keyboard. Thoughts of my childhood neighbor, “Mark,” whirled through my mind. Mark had gained access to opioids when his father was receiving home-based palliative care. Soon after his father died of cancer, Mark died too, of a drug overdose.

I knew that each individual’s story is unique, but I also knew that more than 85% of misused opioids are originally acquired by way of licensed providers. Perhaps, like Mark, John’s son had become addicted through diverted medications – prescriptions that are shared, stolen, or sold. Or perhaps he had received a prescription of his own, possibly at too high a dose, for too long a duration, or with too many underlying risk factors. I could not know for certain; the details of John’s note were sparse.

All I really knew was that, regardless of how the story had begun, I hated how it ended. The thought of this family’s suffering made me shudder. And it stirred my recurring anxiety about whether our stance on involuntary commitment for opioid use disorder placed us on the wrong side of history.

For several decades, we have been moving away from a draconian era of institutionalization when nearly all psychiatric admissions were involuntary and indefinite. The shift was propelled by several factors, ranging from financial to political, ideological, and scientific in nature. One of these factors was the discovery of anti-psychotic medications, which showed it was possible to treat debilitating psychiatric diseases. I was inspired by this pharmacological influence in our shifting views because it has helped reduce the stigma of mental illness and has improved people’s health. Furthermore, it portends additional biomedical advances on the horizon.

The horizon I envision is characterized not only by progress in addiction research, but also by adjustments in our fulcrum for balancing autonomy and safety. It may someday become routine practice to regard patients’ prior values and enjoyment of stability as evidence that they would want treatment for severe addiction, even if their disease leads them to state otherwise. Perhaps we will even clarify and systematize this idea by asking all patients who receive opioid prescriptions to complete psychiatric advance directives that outline care preferences should they later become addicted.

For people like John, the horizon was not close enough. His email granted me exposure to the ramifications of our legislative and administrative actions. The story filled me with humility, but also gratitude. I felt grateful because I was part of a team so dedicated to this cause – a team that, under no circumstances, would lean on a crutch of complexity to shirk responsibility.

Rhode Island is tirelessly carving new paths while also evaluating its tracks. I was proud to be working in a state that was ahead of the curve, not only in opioid policy development, but also in research. For instance, Dr. Josiah “Jody” Rich was studying the impact of offering prison inmates access to all variants of Medication Assisted Treatment, a program that is the first of its kind in the nation. The state also agreed to support my own research proposals that would examine the benefits of behavioral science interventions in preventing opioid misuse.

Photo: Maggie Salinger, MD MPP candidate, holding the Governor’s signed Opioid Executive Order that she helped to compose during her 2017 Dukakis Fellowship in Rhode Island.

Even with robust policy research, the ethical implications of our positions will never be painted in black and white. And John’s email was one of many reminders that our difficult policy decisions bear the gravity of life or death consequences.

Because of this moral weight, and because of the alarming trends of the crisis, people would sometimes ask if I were frustrated with my job. I would tell them that, while I am saddened by our losses to this disease, I could imagine nothing more gratifying than fighting the opioid epidemic. We are mapping out territories that were previously uncharted while weaving together spheres of society that were artificially separate. Through collaboration, evaluation, and determination, I believe we will save lives.

That is why, in photos from my Dukakis Fellowship, I am seen holding the Governor’s Opioid Executive Order with a beaming grin. I am smiling because this document, which outlines our policy plan, is the most important project I have ever worked on. And I am smiling because, at its signing, I could see that so many around me share the Governor’s devotion to action. Behind my smile, though, are thoughts of John and others who are hurting. For you, for all of us, we will keep fighting.

This article is part of the special Inside the Statehouse series, featuring articles by summer 2017 Dukakis Fellows. The Dukakis Fellowship was established by Marilyn and Calvin Gross to honor the career of Governor Michael Dukakis and expose students to leadership roles in state government. The fellows serve in the executive offices of governors across the country working on a variety of policy challenges. For more information, please click here. The experiences represented in this article are the author’s alone.

Photo Credit Frankieleon via Flickr