How can Democratic campaigns get large numbers of their voters to mobilize their friends to vote?

The short answer: no one knows.

To date, the only definite insight is that peer-to-peer voter turnout does not scale through mobile phone apps. Despite numerous “relational organizing” technologies receiving millions in funding and mountains of the press in 2018, insiders tell us the top app was used by just 0.33% of 2018 Democratic voters.

The problem is simple: there’s only a small number of people who will download voter turnout apps.

Relational Organizing scales through non-activists

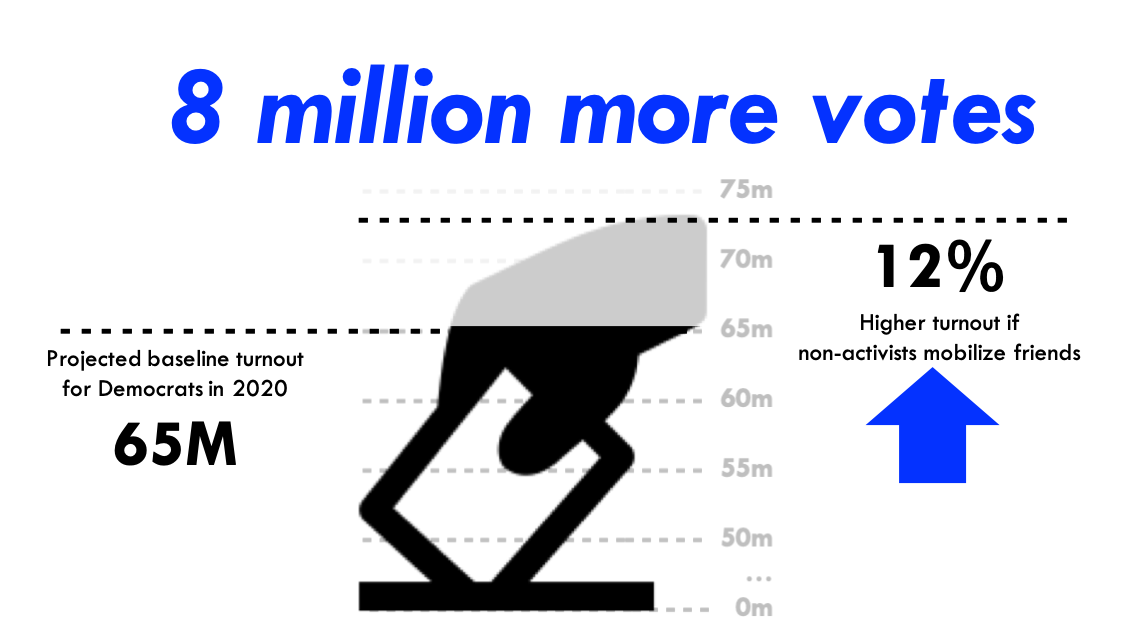

Ahead of 2020, Democrats’ challenge is to develop techniques that spark non-activists to mobilize their friends to vote. Non-activists (Democrats who vote, but don’t volunteer for campaigns) are poised to be far more powerful relational organizers than activists as they: (i) are the majority of Democratic voters, (ii) have stronger ties to irregular voters, and (iii) may be more effective messengers. If Democrats galvanize non-activists, our polling indicates this could unleash 8 million additional votes in 2020.

Today, three behavioral bottlenecks inhibit non-activists from mobilizing their friends: (i) choice overload, (ii) prospective memory failure, and (iii) hassle factors. By following the well-tested design principles that surmount these bottlenecks, Democrats’ 2020 relational organizing programs can be built on the frontier of scientific knowledge.

RESIST: The six principles of a behaviorally-informed non-activist RO program

A review of behavioral science literature suggests six design principles, which we organize via the framework “RESIST”, can spark non-activists to mobilize their friends. These six principles are: Reducing choices, Endorsing categories, Sending reminders, Inducing urgency, Supporting decision-makers, and Truncating steps.

Reducing choices lessens choice overload. For instance, the fewer 401(k) choices offered, the more likely employees are to save for retirement. To reduce choices, non-activists should be asked to mobilize a specific and small number of friends. The number should be specific because behavioral science finds specific goals “consistently led to higher performance than urging people to do their best.” Further, the number should be small because our polling finds non-activists only want to mobilize a few close friends and another study finds that people have no impact on the voting behavior of individuals other than their close friends. While the optimal number of friends non-activists should be asked to mobilize remains undiscovered, it appears to be between two and five.

Endorsing categories also helps overcome choice overload. For example, studies exploring how people purchase magazines find consumers are far more satisfied when options are categorized. Relational organizing programs can suggest categories for the people the non-activist should encourage to vote by, for example, asking “Will you encourage three people to vote? Many voters pick a friend, a co-worker, and a family member.” Alternatively, the program could advise “One young voter, one middle-aged voter, and one elderly voter.”

Sending reminders can reduce prospective memory failure. For instance, sending students SMS reminders about financial aid deadlines boosts re-enrollment rates. And customized reminders appear especially powerful. VoteTripling.org finds that when relational organizing SMS reminders include the names of three specific individuals the recipient should mobilize, 73% more Democrats respond compared to text messages that generically remind them to get three friends to vote. VoteTripling.org’s analyses also find Democrats are most responsive to text messages sent on the weekend between 6-8pm. Outside SMS, polling places are a great place to remind non-activists to mobilize their peers. In 2018, several campaigns in Texas utilized this opportunity by having volunteers hand voters fliers that encouraged the voter to text three friends and provided an image of a sample SMS they could send.

Inducing urgency can also curb prospective memory failure. For example, a charitable giving study by ideas42 finds that messages that elicit urgency around an upcoming deadline sharply increase generosity. Campaigns have many opportunities during the early vote and on Election Day to elicit urgency and prompt non-activists to immediately reach out to their friends. For instance, canvassers can ask supporters if they can take a photo of them calling their friend because the campaign has a goal of posting 100 photos that day of supporters mobilizing friends. Alternatively, micro-incentives can be used to spark immediate action. A nonpartisan example of this occurred last fall when the University of Virginia students stood outside a polling location and dolled out candy to anyone who immediately paused and texted a friend to vote.

Supporting decision-makers can mitigate hassle factors. For example, research finds providing a small amount of support to student loan applicants dramatically boosts college completion rates. Campaign volunteers can support non-activist when deciding which friends to nudge by normalizing any difficulty, for instance with statements like, “Don’t worry if it seems hard. It often takes voters a few moments to decide.” On Election Day, relational organizing programs can continue supporting volunteers by sharing information such as when the polls close and a hyperlink that shows where to vote.

Truncating steps eliminates hassle factors. For instance, a study by the Behavioural Insights Team finds that reducing just one step with tax filings substantially increases conversion rates. One way to trim steps is to make signing up as a relational organizer as simple as possible. The antithesis of this is signups that require downloading a mobile phone app or syncing your phone, email, or social media contact lists with a technology platform. Because non-activists are disengaged, their relational organizing programs must be ultra-lightweight.

CONCLUSION

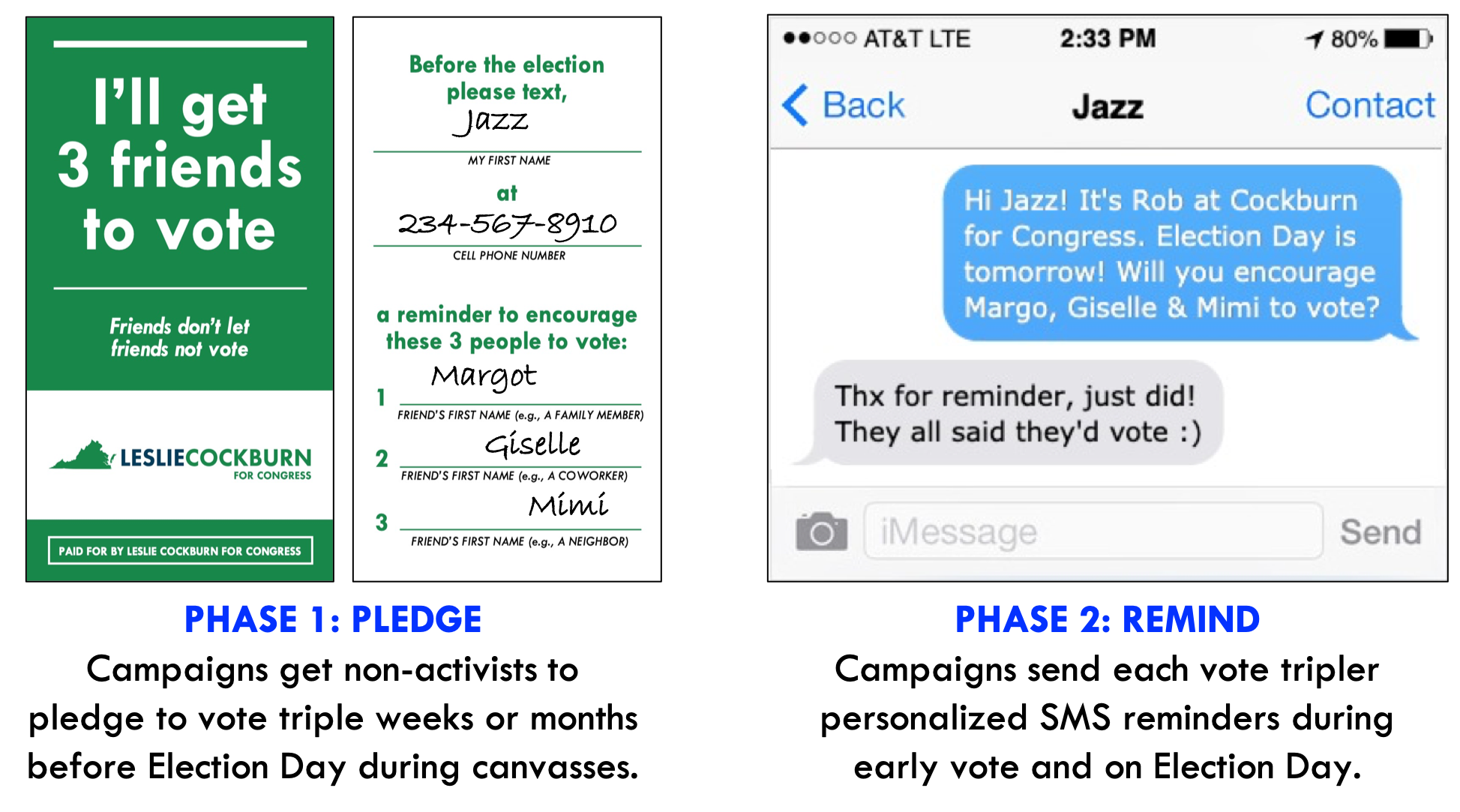

In 2018, dozens of campaigns and voter turnout organizations piloted a GOTV tactic called “vote tripling” that leverages many of these design principles. The vote tripling method begins with campaigns getting non-activists to pledge to get three friends to vote and concludes on Election Day with campaigns sending each “vote tripler” an SMS reminding them of the three friends they pledged mobilize. This intervention reduces options and endorses categories by only asking for three friends and suggesting that non-activists pick “one co-worker, one family member, and one neighbor.” It sends reminders and induces urgency via perfectly-timed text messages saying “Can you text each of them right now?” It supports decision-makers by being deployed by canvassers who patiently aid non-activists until they decide which friends they’ll mobilize. And it truncates steps via an ultra-simple signup process that only involves signing a paper pledge.

Vote tripling is just one of an infinite number of ways to blend these six design concepts into a powerful voter turnout technique. We see vote tripling as merely the first clue towards the yet-to-be-determined game-changing relational organizing technique that will unleash the 8 million votes that rest at the fingertips of Democratic non-activists. As soon as more people begin shuffling these design principle together in new and creative ways, we are confident a brilliant relational organizing technique will emerge. That is how innovation works. The intention of this essay is to spark that innovation.