BY STEFAN NORGAARD AND BRADY ROBERTS

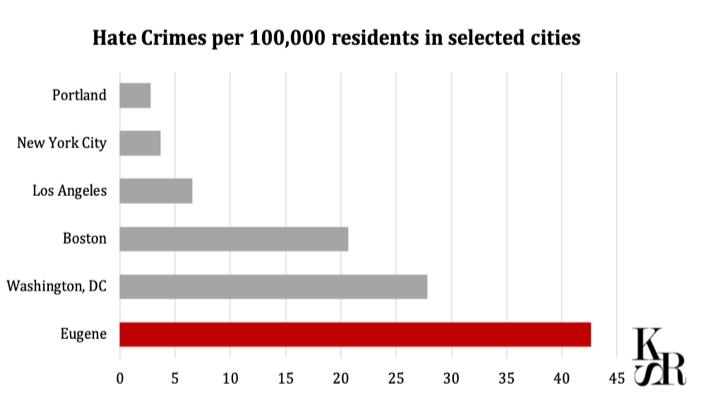

Despite its reputation as a liberal college town, more political-extremist individuals and entities call Eugene, Oregon home than any other United States city as measured by a compilation of official data on crime in the United States published by the FBI. Eugene is victimized by 42 hate crimes per 100,000 residents, per year, in a state with the highest rates of self-reported hate crimes in the country. These metrics indicate the presence of organized white nationalists targeting a small minority community and deeper structural issues including white nationalist ideologies.

As Harvard Kennedy School Professors Mayne and De Jong argue in their paper “State Capabilities” (under review), “wicked problems” like white nationalism are structural in nature and difficult to define. We partnered with the Oregon-based Western States Center to break down the phenomenon into sub-problem “deconstructions” and proposed recommendations for quick adaptation, as well as long-term goals and outcomes of our interventions. The problem deconstructions include:

- The perceived failure of government to fully embrace racial, gender, ethnic, and spatial equity as a central mission to healthy democracy. For example, we spoke with Eugeners on the left and right frustrated by Eugene School District 4J’s tracking program that segments students by race and socio-economic status from a young age.

- A pronounced urban-rural divide that too often segregates and inflames political and ethnic differences and pits a successful urban core against a struggling rural community. In rural Lane County, for instance, the region is under-served by government and still geared toward timber and wood-products extraction, while Eugene’s economic base focuses on education and medical services.

- Historical amnesia and erasure in Eugene by current residents not in keeping with Eugene’s past of white supremacist leadership and to the detriment of forging a truth-driven historical narrative. For example, University of Oregon’s Dunn Hall, named for professor and Ku Klux Klan member Frederick Dunn, was recently re-named at University of Oregon, but the process lacked a sufficiently public conversation engaging Eugene and University of Oregon’s history with the Klan.

- An erosion of white identity due to a collapsing timber industry and an educational system that validates myths of colonialism, while failing to equip young people with tools to have difficult conversations about race and tolerance at home and with each other. White supremacist individuals and entities exist in and around the Eugene, Oregon area.

Working iteratively and collaboratively with the progressive democracy non-profit Western States Center and the City of Eugene’s Office of Human Rights and Neighborhood Involvement (HRNI), we crafted an implementation framework and specific recommendations about how the city could respond to white nationalism.

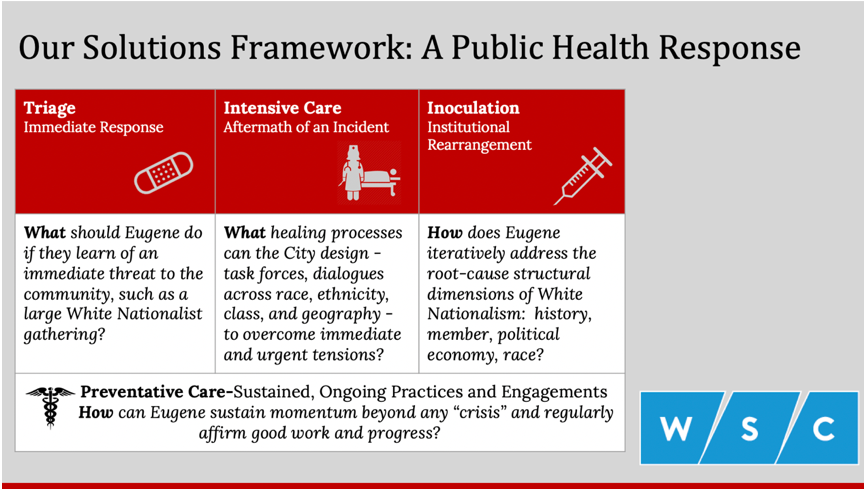

We view white nationalism as a social disease and developed a framework centered on a public health response:

- ‘“Triage’ and Rapid response” recommendations focus on immediate community threats;

- “Intensive care” recommendations consider healing processes, dialogues, and tasks forces across geography and identity groups to bridge the gap between immediate crisis and longer-term solutions; and

- “Inoculation” recommendations seek to change institutions, norms, practices, and systems, getting at the deeper causes of white supremacy throughout Eugene’s history, and enduring through to the present day. Examples of work at the “inoculation” level include Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative, and teaching modules from the UK-based organization “Hope Not Hate.”

Undergirding this framework is the idea of primary care: a renewed commitment to the work of racial equity through constant assessment, analysis, and conversation between institutions.

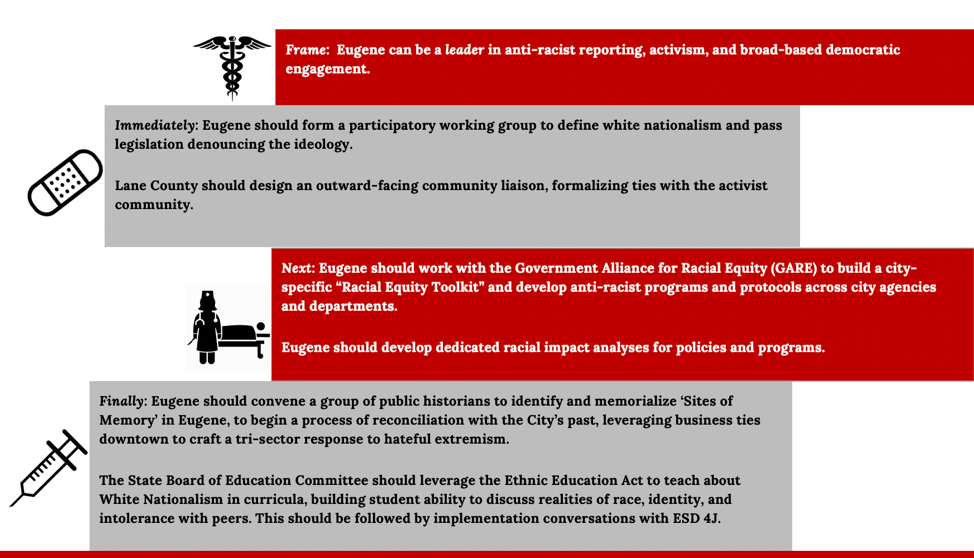

With a problem of the scope and size of contemporary white nationalism, no one solution will ever serve as a “silver bullet.” However, a variety of interventions that are asset-based, context-specific, and collaboratively honed have the potential to change the narrative around white nationalism in Eugene. Our ultimate vision guiding these recommendations is as follows: Eugene can serve as a regional and nationwide leader in anti-racist reporting, activism, and broad-based democratic engagement.

Through our research process, we ultimately proposed a six-step sequence of recommendations for racial equity and anti-hate work in Eugene and Lane County. The recommendations are:

- Convene a participatory working group to define white nationalism and codify the chosen approach through an ordinance or resolution. We drafted such a resolution, based on one recently passed successfully by the Portland, Oregon city council;

- Design an outward-facing Lane County position committed to Equity and Access, and to support ongoing engagement with and among activist and community groups;

- Develop a racial equity action plan for all levels of city government, including through a central leadership “Racial Equity Team,” and with Racial Equity representatives hired across agencies and departments in the city. Race Forward’s Government Alliance for Racial Equity (GARE) has developed and deployed these action plans in over 160 local and regional government jurisdictions nationwide, though not Eugene;

- Couple the racial equity action plan with concrete “racial equity tools,” developed by GARE, community groups, and the City of Eugene together;

- Convene a group of public historians to identify, memorialize, and celebrate “Sites of Memory” in Eugene’s public spaces. Historians like the University of Oregon’s Laura Pulido, who is developing an atlas of Oregon’s white supremacist past, would serve as effective leaders in this effort;

- Work with State Boards of Education and Legislators developing the Ethnic Education Act to develop statewide curricular resources about how Oregon teaches its history, and ensure white nationalism in historic and contemporary forms is explicitly discussed.

Racial ideologies and histories are deeply rooted in Eugene and elsewhere, and have been complexly interwoven with constructs of race and class over time. We are far from the first to propose anti-racist work in Eugene, and will surely be followed by countless others. But our approach focuses on city employees and elected officials as potential conveners and problem-solvers. The complex work of democratic inclusion at the city-level necessitates tradeoffs and is not easy, financially and politically. Our recommendations, at their absolute best, will only continue to bolster a much longer term process of recognition, reconciliation, and healing across difference in and around Eugene. We recommend that Eugene, Lane County, and Western States Center, boldly and courageously, bring people together with an aim to do so.