“For every dollar and every minute we invest in improving AI, we would be wise to invest a dollar and a minute in exploring and developing human consciousness.” —Yuval Noah Harari1

In June 2020, the veritable explosion of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted more than 130 countries to issue a statement on the burgeoning “infodemic.” The statement warned that “as COVID19 spreads, a tsunami of misinformation, hate, scapegoating and scare-mongering has been unleashed.”2

Though online misinformation predates the pandemic era, it came into stark relief during the pandemic owing to its unprecedented geographic spread, its cross-sectoral impact, its effect on various industries from health care and travel to education and employment, and the acutely government-centred nature of the policy response.

Crises give rise to uncertainties, which cause an increase in the demand for information. This underlying demand and an absence of a clear stream of information from authentic sources create a thriving environment for misinformation to prosper. A study of 225 instances of COVID-19 misinformation identified “misleading or false claims about the actions or policies of public authorities” as the single largest category.3

This is exacerbated by an information ecosystem where engagement is driven by the promotion of “more emotional and provocative content,” which fosters “rage and misinformation.”4 These factors uniquely endow misinformation with the capacity to complicate our response to every other policy challenge, especially that of climate change.5

Misinformation will predictably complicate our response to the climate crisis, aided and abetted by rapid developments in the field of artificial intelligence (AI).

Disinformation Meets Artificial Intelligence

Within a year since AI tools became available for mass public use, they have already generated believable images of events that never occurred—of President Trump being arrested in New York and of astronauts faking the 1969 moon landing—based on a single text prompt.6 Companies are already in the advanced stages of developing AI that convert text prompts to videos.7 A future where conspiracy theories about the moon landing are supported by compelling images and videos is just around the corner. News websites that are “almost entirely written” by AI are already a reality.8

The Limits of Regulation and Enforcement

The response to the misinformation challenge has largely centred around two poles – social media regulation and law enforcement. Both approaches, while certainly necessary, face inherent limitations. Companies can flag and take down certain posts, but their capacity to do so is limited by the quantity of content generated daily. Of the content that is fact-checked and flagged, oversight ends when it leaves the visible, public space of social media and enters the end-to-end encrypted space of private messenger apps, where misinformation finds a safe, untraceable space. France, Germany, and several other countries have passed laws to curb the spread of misinformation.9 But government agencies can only act against a limited number of cases at any given point of time. The cycle of identification, arrest, and prosecution detracts from core agency functions and is unsustainable in the long term.

Building Resilience to Misinformation

If the past two decades are any indicator, misinformation and information technology (IT) are clearly in a long-term relationship. Any effort to build resilience against them calls for a whole-of-society approach. The public education system offers the opportunity to pursue this goal at scale. Teachers, social scientists, IT specialists, and experts in pedagogy will have to come together and formulate a curriculum that is specific to local contexts, flexible, and avowedly non-partisan. This effort is most likely to succeed if it follows a process of political consensus.

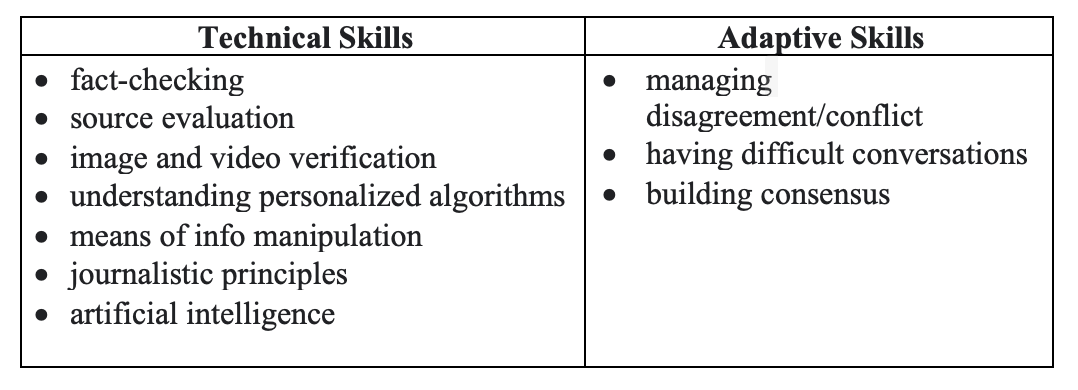

Media and information literacy ought to be a separate subject through school and college. Children would begin with learning technical skills and progress towards skills that deal with adaptive challenges.10 Taking a cue from the framework developed by Prof. Ronald Heifetz at the Harvard Kennedy School, the technical skills would cover the domain of fact-checking, while the adaptive skills would familiarize them with the ability and mindset needed to deal with ambiguity, have difficult conversations, manage disagreements and conflict, and build consensus in an increasingly complex world.11

Educators working on these curricula do not need to start from scratch. They can build on resources like the “Checkology” platform from the News Literacy Project12 or the ANNIE toolkit, a collaborative effort of educators across multiple universities.13

Frontrunners in Education Reform

Since 2016, Finland has introduced information literacy and critical thinking across subjects in their school curriculum.14 It consistently tops the list of European countries in the Media Literacy Index.15 In 2021, the government of Kerala, India’s most literate state, launched a program titled Satyameva Jayate (Sanskrit for “Truth Alone Triumphs”) which familiarized two million students with concepts like personalized algorithms, filters bubbles, the methods of manipulating information, and the means through which they could counter misinformation.16 Parts of the curriculum were drawn from the resources developed by the DC-based News Literacy Project.

Technological Transitions: Asset to Adversary

We often underestimate the power and speed with which disruptive technologies can subvert as much as they augment the public good. In his book “A Promised Land,” President Barack Obama fondly recalls his victory in the 2008 Idaho Democratic primary, where he won five times as many delegates as Hilary Clinton thanks to volunteers “using social media tools like MySpace and Meetup to build a community.”17 In 2016, he lamented in an interview with Bill Maher over the failure of school systems in building capacities for critical thought among children.18 Speaking at Stanford in 2022, President Obama called for urgent public regulation of social media, stating that the implications of AI and disinformation “for our entire social order are frightening and profound.”19 It took a little over a decade for the same technology that propelled President Obama to office in 2008, in his words, to pose a threat to our social order as we know it.

Conclusion

Societies where critical thinking and scepticism towards misinformation are common traits will be able to weather the impact of information warfare. Regulation and enforcement certainly have a role to play, and they could only be more effective if supported by a larger community that understands the depth of the problem and the broad contours of the solution. Research on inoculation against misinformation, which seeks to build resilience through increasing awareness of methods of manipulation and deception has shown promising results.20 We ought to seek to reach a point where scepticism towards online information is as common a piece of wisdom as refusing candy from a stranger.

Photo credit: Christian Battaglia via Unsplash

[1] Yuval Noah Harari, “Why Technology Favors Tyranny,” The Atlantic, August 30, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/yuval-noah-harari-technology-tyranny/568330/.

[2] United States Mission to the United Nations, “Cross-Regional Statement on ‘Infodemic’ in the Context of COVID-19,” United States Mission to the United Nations, June 12, 2020, https://usun.usmission.gov/cross-regional-statement-on-infodemic-in-the-context-of-covid-19/.

[3] “Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, April 7, 2020, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation.

[4] “Five Points for Anger, One for a ‘like’: How Facebook’s Formula Fostered Rage and Misinformation,” Washington Post, October 26, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/10/26/facebook-angry-emoji-algorithm/.

[5] Jonathan Rothwell and Sonal Desai, “How Misinformation Is Distorting COVID Policies and Behaviors,” Brookings (blog), December 22, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-misinformation-is-distorting-covid-policies-and-behaviors/.

[6] Tiffany Hsu and Steven Lee Myers, “Can We No Longer Believe Anything We See?,” The New York Times, April 8, 2023, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/08/business/media/ai-generated-images.html.

[7] Cade Metz, “Instant Videos Could Represent the Next Leap in A.I. Technology,” The New York Times, April 4, 2023, sec. Technology, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/04/technology/runway-ai-videos.html.

[8] “Rise of the Newsbots: AI-Generated News Websites Proliferating Online,” NewsGuard (blog), accessed May 11, 2023, https://www.newsguardtech.com/special-reports/newsbots-ai-generated-news-websites-proliferating.

[9] “A Guide to Anti-Misinformation Actions around the World,” Poynter (blog), accessed June 13, 2023, https://www.poynter.org/ifcn/anti-misinformation-actions/.

[10] “The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World,” accessed June 7, 2023, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/practice-adaptive-leadership-tools-and-tactics-changing-your-organization-and-world.

[11] Adam McCauley Summer 2020, “HKS Faculty Teach Leaders How to Make Better Decisions amid Uncertainty,” accessed May 11, 2023, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty-research/policy-topics/public-leadership-management/hks-faculty-teach-leaders-how-make.

[12] “Checkology | The News Literacy Project,” accessed May 1, 2023, https://get.checkology.org/.

[13] “ANNIE EDUCATOR’S TOOLKIT (Work-in-Progress),” accessed June 7, 2023, https://toolkit.annieasia.org/.

[14] Jon Henley, “How Finland Starts Its Fight against Fake News in Primary Schools,” The Guardian, January 29, 2020, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/28/fact-from-fiction-finlands-new-lessons-in-combating-fake-news.

[15] “How It Started, How It Is Going: Media Literacy Index 2022,” Osis.Bg (blog), April 20, 2018, https://osis.bg/?p=4243&lang=en.

[16] “Sathyameva Jayathe: Kerala Initiative Aims to Educate Students in Spotting Fake News,” October 26, 2022, https://frontline.thehindu.com/news/sathyameva-jayathe-kerala-initiative-aims-to-educate-students-in-spotting-fake-news/article66056748.ece.

[17] Barack Obama, A Promised Land (New York, United States: The Crown Publishing Group, 2020), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/harvard-ebooks/detail.action?docID=6397530.

[18] President Obama on Atheism | Real Time with Bill Maher (Web Exclusive), 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCb3CaLpfmk.

[19] Reclaim The Net, “Transcript of President Barack Obama’s Speech at Stanford, April 21, 2022,” Reclaim The Net, April 23, 2022, https://reclaimthenet.org/transcript-of-president-barack-obamas-speech-at-stanford-april-21-2022.

[20] Jon Roozenbeek Linden Melisa Basol, Sander van der, “A New Way to Inoculate People Against Misinformation – By Jon Roozenbeek, Melisa Basol, and Sander van Der Linden,” Behavioral Scientist (blog), February 22, 2021, https://behavioralscientist.org/a-new-way-to-inoculate-people-against-misinformation/.