BY KATIE BURHKART AND NATALIE UNTERSTELL

The Amazon rainforest and the Arctic Ocean both conjure images of frontier lands: the Arctic as a cold and desolate region inhabited by reindeer and polar bears, and threatened by a warming climate; the Amazon as a dense, humid forest teeming with wildlife and threatened by deforestation. Both are seen as distant areas, rich in natural resources, awaiting future exploitation and occupation.

In fact, neither region meets the accepted definition of a “frontier.” For one, neither is a “border between two countries,” as each ecosystem spans various countries.[i] Also, neither the Amazon nor the Arctic are “a region that forms the margin of settled or developed territory” as they have been home to humans since time immemorial.[ii] The inhabitants of these regions have not just lived on the margins of other societies, but have developed their own vibrant societies with rich cultures and traditions adapted to the local conditions.

This misconceived frontier image frustrates practical policymaking. Neither region is a pristine space devoid of human contact, so the choice is not simply between commercial exploitation and environmental preservation. The rights of indigenous peoples and long-term residents must be considered, including rights to development that can sustain their communities into the future.

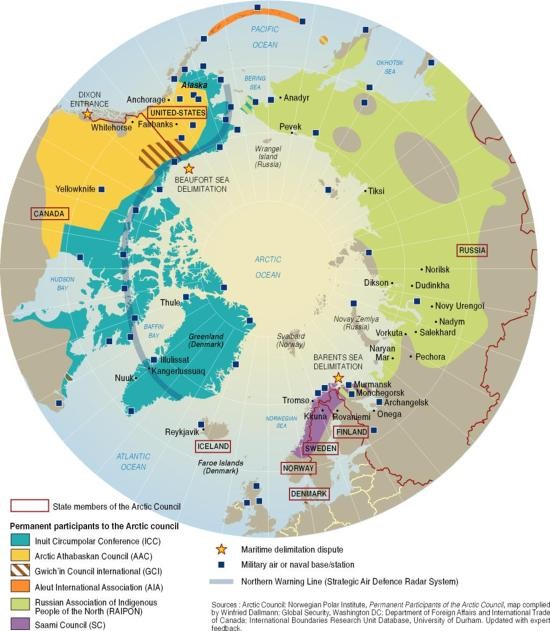

The regions are not devoid of political governance either. The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) coordinates between eight nations, and interacts with multilateral institutions and outside actors to formulate and implement regional policy.[iii] In the north, the Arctic Council is the primary governance body that brings together eight Arctic nations, indigenous communities, and extra-regional states and organizations.[iv] Aside from these main bodies, both regions have multiple layers of governance ranging from local cooperation structures to regional resource agreements to overarching international law.

The most critical similarity between the regions is their importance to the global climate. The Amazon is the world’s largest forest: its 390 billion trees store around 86 billion tons of carbon. The preservation of this region protects a vital reservoir of carbon dioxide, an important factor in preventing catastrophic climate change.[v] In the Arctic, the polar ice cap regulates global weather patterns through the circulation of cold water and air to other regions of the world. But as the polar ice cap shrinks more every summer, weather patterns are expected to grow more volatile and, in a vicious feedback loop, the release of methane from the melting permafrost is anticipated to accelerate global warming.[vi]

The challenges of mitigation and adaptation are immense in both regions, and can only be overcome by cooperation. Both regions have implemented some successful policies, but as climate change accelerates, policy makers must also accelerate their efforts to serve the local populations and confront regional and global challenges. The ACTO and the Arctic Council can build on each other’s success to deal with these challenges. The following four lessons show how the governing bodies could learn from each other, by:

1. fostering meaningful indigenous participation in regional diplomacy;

2. understanding the regional environment;

3. incorporating traditional knowledge; and

4. developing sustainable business models.

Lesson #1: Fostering Meaningful Indigenous Participation in Regional Diplomacy

From the inception of the Arctic Council, indigenous groups have been directly involved in governance. The Amazon region has much to learn from this model. The opening paragraph in the Arctic Council Declaration of 1996 reads:

Affirming our commitment to the well-being of the inhabitants of the Arctic, including special recognition of the special relationship and unique contributions to the arctic of indigenous people and their communities.[vii]

While indigenous groups are designated as “Permanent Participants” (PPs) instead of voting “Members” like the eight nation states, their involvement is nonetheless exceptional. The power granted by the Arctic Council Declaration is a form of soft law that requires consultation of indigenous peoples before decisions are made by consensus of the eight nations. Despite the legal limitations of the organization and separate status, the permanent participants hold “de facto power of veto”[viii] over any proposal, an unprecedented position in international governance bodies.[ix]

The influential position of indigenous groups in Arctic governance has strengthened a pan-Arctic identity and granted greater legitimacy to the Arctic Council.[x] The Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples Secretariat (IPS) has allowed for a cohesive voice of the Arctic indigenous peoples through coordination and communication among the PPs and between these groups and the Arctic Council. The formal role of indigenous peoples gives legitimacy to the Arctic Council because it gives voice to the original inhabitants of the region. The work of the Arctic Council, especially with regard to environmental conservation, is also legitimized through the involvement of the indigenous groups.[xi]

The involvement of indigenous peoples in Arctic Governance has also led to concrete steps to protect their livelihood. For example, the evidence of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the traditional foods of the Inuit and evidence of health effects in the northern populations gave a face to the threat from POPs.[xii] These findings made the argument for a global treaty more compelling, and led to the 2011 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which acknowledges the threat to Arctic communities in the preamble.[xiii]

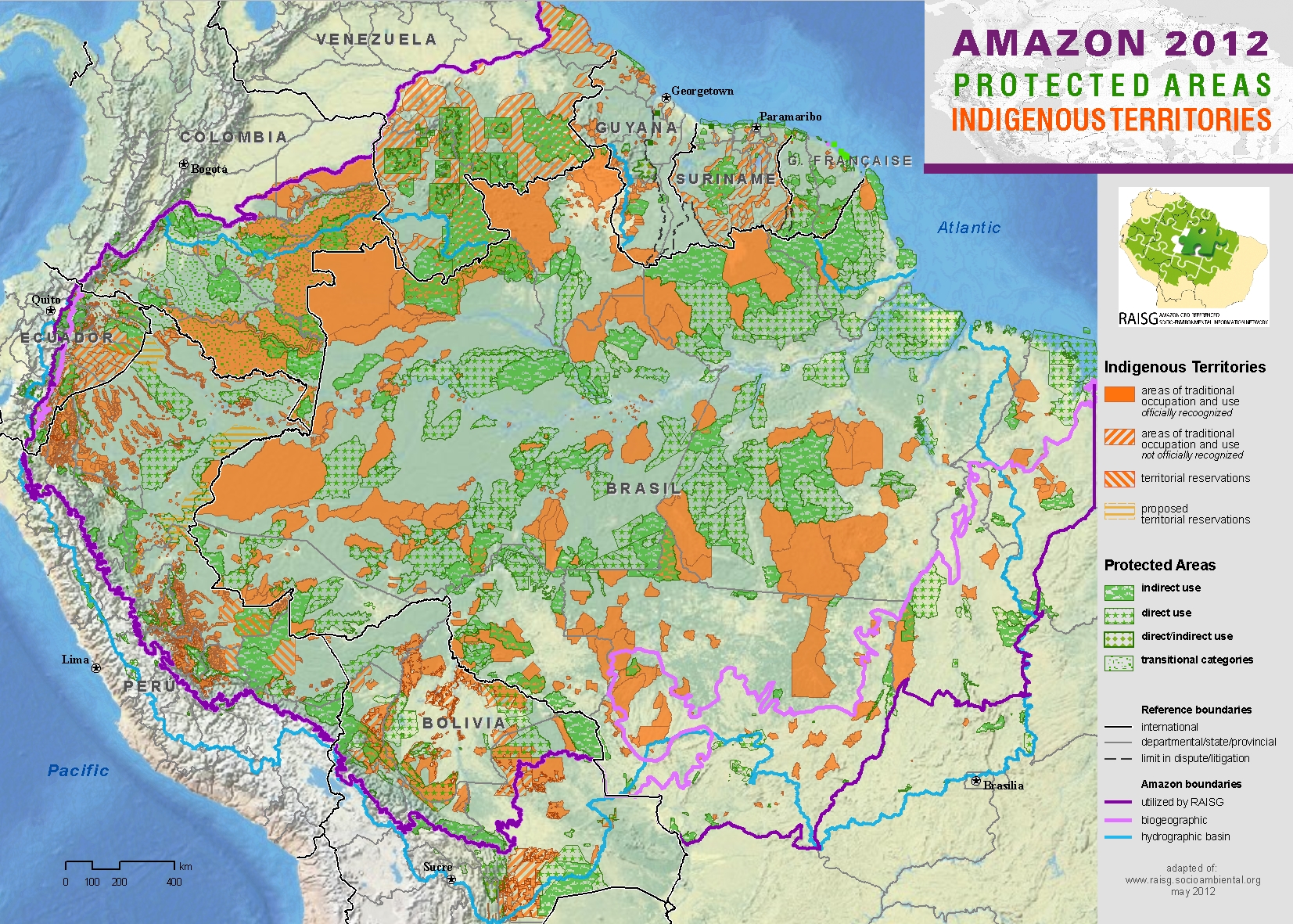

By contrast, the indigenous peoples in the Amazon have no political status. The ACTO aims to protect the rights of indigenous peoples and support their well-being, but there is no formal role for indigenous peoples in the governance structure. The Organization has negotiated a cooperation agreement with the Confederation of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA);[xiv] however indigenous peoples have limited participation in setting and managing any agenda. For example, the ACTO has funded cooperation efforts related to the health of voluntarily-isolated indigenous populations. Nevertheless, these policies are written by national government agencies interested in delivering services to indigenous populations, rather than involving them in political decision-making.[xv]

As in the Arctic, the meaningful inclusion of indigenous peoples’ voices in the ACTO’s structure could provide the organization with a genuine Amazonian identification. Moreover, it would place sustainable development work at the center of the regional cooperation, as indigenous Amazonians are presently at the forefront of conservation efforts. In Brazil, with historically high level of deforestations, indigenous territories are generally better conserved than any other lands.[xvi]

Embracing indigenous peoples’ participation in ACTO’s space could correct the view of the region as a frontier as well. The invisibility of the indigenous peoples in the organization mirrors the view of the empty Amazon.

The governance structures of the Amazon and the Arctic are distinct in many ways. For example, the Amazon’s ACTO is a treaty organization and the Arctic Council is not. However, the Arctic Council remains the global standard for ensuring systematic inclusion of indigenous groups. The ACTO should look to the successful inclusion of indigenous groups in the north as an example of effective governance processes that would enhance the ACTO’s legitimacy and enable environmental protection efforts. In order to succeed in the regional cooperation endeavor, national governments and the ACTO need as much indigenous engagement as national diplomatic efforts.

Lesson #2: Understanding the Regional Environment

A second lesson from the Arctic that applies to the Amazon region is the environmental monitoring efforts that have resulted in regional policies and international treaties against harmful pollutants. The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) is an internationally coordinated, science-based assessment, designed to support policy and decision-making. AMAP was started before the Arctic Council’s creation and is now one of six working groups of the regional body.[xvii]

From the outset, AMAP was designed to go beyond monitoring and identify ways to “prevent, minimize and mitigate” the adverse effect of pollutants, climate change, and other threats to the Arctic environment.[xviii] Acknowledging that the majority of research being conducted at the time was national in nature, the Inari Declaration described an “urgent need for cooperation” with existing national and NGO projects to create a regional understanding of the Arctic environment.[xix] The same urgency is required in the Amazon.

The work of the AMAP has impacted the international treaty negotiations, especially against pollutants such as POPs and heavy metal pollutants.[xx] The detrimental impacts of POPs on the Inuit population in the Arctic (as discussed in Lesson #1) were first published in an AMAP assessment report.[xxi]

In the Amazon, a similar initiative is sorely needed, as there is no such mechanism providing basin-wide climate information and monitoring. Efforts in this direction are underway, but lack the comprehensive nature of the AMAP. In addition to Amazon states sharing monitoring technology through situation rooms in different ACTO countries, there are ongoing collaborative efforts among Amazonian indigenous and NGO networks, scientists, and policy experts. An important example is that sixteen research organizations have been able to systemize, update, and integrate their databases within the scope of the Network of Environmental Geographic Information (acronym RAISG in Portuguese and Spanish).[xxii] The ACTO project aims to transfer Brazilian technology to monitor forest cover,[xxiii] and the civil society-run RAISG has been able to assemble information from different sources to identify threats and pressures to the forests and indigenous peoples.[xxiv]

To transform environmental monitoring into impactful policy outcomes, an effort to analyze and report on the region as a whole is needed. Monitoring deforestation is not the only measure of the Amazon environmental health. Other areas, like water quality and biodiversity, can provide an important basis for ACTO to support both regional and national decision-making processes. The Arctic has been able to recognize the value of using inputs generated by independent sources so that information is useful for different actors. The ACTO should pursue a similar arrangement in addition to their technology sharing programs.

Lesson #3: Incorporating Traditional Knowledge

In the Amazon, the indigenous communities developed extensive knowledge and practices for using resources sustainably over millennia.[xxv] More recently, the governance of territories has evolved to include both traditional knowledge, generally referring to the way of knowing and the recurrent practices of indigenous and tribal peoples, and modern technology..[xxvi]

In the Rio Negro river basin, home to forty indigenous peoples along the borders of Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela, the “Management of the World” project enables a shared understanding of particular challenges and the emergence of agreements and proposals for relevant public policies.[xxvii] Indigenous researchers analyze changes in the agricultural systems and fisheries, even identifying potential impacts of climate change. The cumulative and collaborative research then turns local observations into a series of maps and graphs, which are used as ecological calendars by local communities to manage their natural resources.[xxviii]

This research collaboration requires a long-term, intimate understanding of the region that traditional knowledge can provide. It also places researchers and indigenous leaders on an equal footing on the issues of environmental management and governance policies. In Brazil and in Colombia, national governments have started to recognize such processes as official “long-term development plans” for these communities.[xxix], [xxx]

The Arctic Council has made efforts to incorporate traditional knowledge into its projects and reports genuinely and routinely. At the 2015 Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting, the Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group presented “Recommendations for the Integration of Traditional and Local Knowledge into the Work of the Arctic Council.”[xxxi] The report acknowledges that the organization must do better at incorporating traditional knowledge into projects, but falls short of providing a plan to do so. The recommendations merely state that standards are needed in order to achieve “systematic inclusion of traditional and local knowledge in the work of the Arctic Council.”[xxxii]

In the Arctic, indigenous groups are often called on to provide input to large-scale, transnational projects such as the AMAP. This is partially due to the deliberate engagement of indigenous communities at the international level that often exceeds engagement with national or subnational governments. As one critic has pointed out, “Such a formulation seems to suggest that indigenous traditions should provide answers to problems created by modern states in terms convenient for modern states.”[xxxiii]

Both the Amazon and the Arctic have not pursued a systematic approach to the inclusion of traditional knowledge in projects undertaken by the regional governance bodies, despite recognizing the value in doing so. The “Management of the World” project in the Rio Negro basin can act as a model for traditional knowledge inclusion in Arctic Council projects. However, both regions will benefit from a more systematic inclusion of traditional knowledge in their regional projects. Both should employ the Inuit concept of piliriqatigiinniq: “working together for the common good.”[xxxiv]

Lesson #4: Developing Sustainable Business Models

The two regions have taken distinct paths to achieve sustainable development. In the Arctic, regional norms have guided development practices whereas in the Amazon development has been constrained by regulations. Neither approach has proven successful, but learning from each other could enhance each region’s outcome.

This issue is especially ripe for cooperation between the two regions because of how business models proliferate globally. Although minerals are sovereign resources, and thus not jointly managed by nations in the Amazon or in the Arctic, the development of business models for exploring them in one particular country may affect how these activities are developed in other areas in the same region. Investments are still in their infancy in both regions, making the establishment of norms and regulations for sustainable development critical.

In the Amazon, the discussion has centered on assessing the overall impact of extractive industries instead of a project-by-project evaluation. Proposed policies like declaring a moratorium on exploration, levying an environmental tax on companies when they begin exploring for natural resources, designating no-go zones, and paying for avoided extraction address the trade-offs of extraction.[xxxv].These policy options discipline governments and the private sector to ensure the total social cost is accounted for at the outset of a development project. So far, however, none of these regulations have been enacted, leaving both the revenues and the impacts of the oil and gas business, as well as those of mining, to sectoral and national norms.

In the Arctic, development has been constrained by norms of environmental stewardship which guide national policies and business practices. These norms continue to develop, such as the newly released Arctic Investment Protocol. Created by the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on the Arctic, the voluntary principles emphasize development and investments that prioritize environmental stewardship and local and indigenous communities.[xxxvi] Guggenheim Partners, a US-based investment firm, was the first business to endorse the investment protocol and plans to provide “long-term capital that carefully weighs environmental and societal impact.”[xxxvii] As the Arctic ice melts and the region becomes more accessible, norms may not be enough to balance the environmental and social interests.

Both norms and regulations are powerful in their own right, but would have unprecedented impact on sustainable development if fused. As the global demand for food, water, and energy grows with the population, finding a risk management model that motivates business choices that are responsible to environmental concerns is in the best interests of the Amazon and Arctic inhabitants.

MOVING FORWARD

Shared ecosystems and the belief that common values must be collectively safeguarded have triggered international cooperation in the Amazon and the Arctic. The lessons proposed here aim to further this cooperation through the principles of inclusion and shared responsibility. The ACTO, Arctic Council, and other regional bodies should seek to learn from each other through increased multi-stakeholder diplomacy. Sharing these lessons will allow both regions to thrive in the midst of increasingly complex challenges.

The Amazon and the Arctic are not the only regions that can offer examples of successful governance structures and strategies, but the current scholarship on regional governance structures is lacking. Further comparative research, such as examining trade blocs for models of sustainable development, could also contribute to the development of effective governance in critical regions such as the Amazon and the Arctic.

Katie Burkhart is a US Navy Veteran and Masters in Public Policy graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government where she focused on maritime security and the Arctic region. She works in the US Senate on defense and foreign policy.

Natalie Unterstell is an experienced environment and climate change professional from Brazil. Natalie holds a Bachelor’ degree in Business Administration from Fundacao Getulio Vargas (2004) in Brazil and she is a Master on Public Administration candidate at Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Photo Credit: Flickr, Creative Commons

[i] Merriam Webster offers two definitions of frontier: “1. a border between two countries;

2. a region that forms the margin of settled or developed territory.” Citation: “Frontier,” Merriam-Webster.com, 2015, accessed 6 January 2016,http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/frontier

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] As per ACTO’s website accessed in February 27th, 2016: www.acto.org

[iv] As per the Arctic Council website accessed in February 27th, 2016: www.arctic-council.org/

[v] Rhett A. Butler, “The Importance of the Amazon Rainforest,” Mongabay.com, Accessed 1 February 2016, http://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/amazon_importance.htm#sthash.PpbI8Fes.dpuf.

[vi] Kevin Schaefer et al., 2014. The impact of permafrost on of the permafrost carbon feedback on global climate. 2014 Environ. Res. Lett. 9 085003. Available online at: http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/9/8/085003/pdf;jsessionid=FDE1EBC6FE57DF3A3740AD48B110B710.c1

[vii] Also known as the Ottawa declaration. Arctic Council, Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council (Ottawa, Canada) September 19, 1996. Accessed at: https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/bitstream/handle/11374/85/00_ottawa_decl_1996_signed%20%284%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[viii] Timo Koivurova and Leena Heinämäki, “The participation of indigenous peoples in international norm-making in the Arctic,” Polar Record 42, no. 2 (2006): 104.

[ix] Jennifer McIver, “Environmental Protection, Indigenous Rights and the Arctic Council: Rock, Paper, Scissors on the Ice?” 10 Georgetown International Environmental Law Review. 147 1997-1998: 168. Accessed at: http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/gintenlr10&div=11&id=&page=

[x] For a detailed discussion, see Timo Koivurova “The Status and Role of Indigenous Peoples in Arctic International Governance,” 25 April 2014, The Yearbook of Polar Law Vol. 3, (2011), 169-192.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Snodgrass, J. Josh. “Health of Indigenous Circumpolar Populations.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 69-87.

[xiii] United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) as amended 8 May 2009, Geneva, Switzerland. Accessed at: http://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/Overview/TextoftheConvention/tabid/2232/Default.aspx

[xiv] UNDP, GEF, 2011. International Waters: Review of Legal and Institutional Frameworks. Available online at http://www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/environment-energy/www-ee-library/water-governance/international-waters-review-of-legal-and-institutional-frameworks/IW_Review_of_Legal_Instl_Frameworks_Project_Report.pdf

[xv] “La Coordinación de Asuntos Indígenas,” ACTO, accessed 15 January 2016, http://otca.info/portal/coordenacao-interna.php?p=otca&coord=3.

[xvi] D. Nepstad, S. Schwartzman, B. Bamberger, M. Santilli M, D. Ray, et al. Inhibition of Amazon Deforestation and Fire by Parks and Indigenous Lands. Conservation Biology 20, no. 1 (2006):65–73.

[xvii] “Alta declaration,” Alta, 13 June 1997, accessed http://library.arcticportal.org/1271/1/The_Alta_Declaration.pdf

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Inari Declaration on the occasion of the Third Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council, 10 October 2002, accessed at http://library.arcticportal.org/1267/.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] AMAP, 2010. AMAP Assessment 2009 – Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in the Arctic. Science of the Total Environment Special Issue. 408:2851-3051. Elsevier, 2010. http://www.amap.no/documents/doc/amap-assessment-2009-persistent-organic-pollutants-pops-in-the-arctic/45

[xxii] As per the RAISG’s website accessed in February 26th, 2016: http://raisg.socioambiental.org/

[xxiii] As per announcement at http://nr.iisd.org/news/brazils-amazon-fund-to-extend-anti-deforestation-support-to-acto-countries/ and http://www.amazonfund.gov.br/FundoAmazonia/fam/site_en/Esquerdo/Projetos/Lista_Projetos/OTCA

[xxiv] Personal communication with ACTO manager, Mr. Carlos Aragón, in December 28th, 2015.

[xxv] Claudia Sobrevila, 2008. The role of indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation: the natural but often forgotten partners. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2008/05/9633734/role-indigenous-peoples-biodiversity-conservation-natural-often-forgotten-partners

[xxvi] It must be acknowledged that the “traditional knowledge” definition is not universal. While the ACTO has accepted the definition of traditional knowledge as outlined in the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, there is no accepted definition within the Arctic Council. The Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC), a representative organization of many Inuit communities across the Arctic, holds a different definition of traditional knowledge, emphasizing a system of knowledge or ‘way of knowing’ that goes “beyond observations and ecological knowledge.” Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples Secretariat, “Ottawa Traditional Knowledge Principles,” n.d.. Accessed at: http://www.arcticpeoples.org/images/2015/ottradknowlprinc.pdf

[xxvii] As per project’s website accessed in February 26th, 2016: http://ciclostiquie.socioambiental.org/en/index.html

[xxviii] “The Annual Cycles of the Indigenous People of the Rio Tiquié,” Manejo do Mundo, ISA, accessed 15 January 2016, http://ciclostiquie.socioambiental.org/en/index.html.

[xxix] Luis Abraham Cayón Duran, 2014. Planos de vida e Manejo do mundo. Cosmopolítica do desenvolvimento indígena na Amazônia colombiana. Interethnic@: Revista de Estudos em Relações Interétnicas, Brasília, v. 18, n.1, 2014. Available at: http://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/interethnica/article/view/12360

[xxx] Decree No. 7.747 of 2012 establishing the National Policy on Territorial and Environmental Management of Indigenous Lands (PNGATI) in Brazil. Available at: http://faolex.fao.org/cgi-bin/faolex.exe?rec_id=120048&database=faolex&search_type=link&table=result&lang=eng&format_name=@ERALL

[xxxi] Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG) “Recommendations for the Integration of Traditional and Local Knowledge into the Work of the Arctic Council,” 2015. Accessed at: http://hdl.handle.net/11374/412

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Julie Cruikshank, “Uses and Abuses of ‘Traditional Knowledge’: Perspectives from 17 the Yukon Territory,” Chapter 2 in Cultivating Arctic Landscapes: Knowing and Managing Animals in the Circumpolar North, ed. David G. Anderson and Mark Nuttall (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), 22.

[xxxiv] Gwen Healey and Andrew Tagak Sr., “PILIRIQATIGIINNIQ ‘Working in a collaborative way for the common good’: A perspective on the space where health research methodology come together,” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 7 no. 1 (2014), http://www.isrn.qut.edu.au/publications/internationaljournal/documents/volume7_number1_14-Healy.pdf

[xxxv] An example is the symbolic Yasuní Program, championed by the Government of Ecuador, as explained by Carlos Larrea at “Yasuni-ITT Initiative: A Big Idea from a Small Country,” in United Nations Development Program, 2009, accessed at: mdtf.undp.org/document/download/4545.

[xxxvi] “Guggenheim Partners Endorses World Economic Forum’s Arctic Investment Protocol,” Guggenheim Partners, January 21, 2016, https://www.guggenheimpartners.com/firm/news/guggenheim-partners-endorses-world-economic-forums.

[xxxvii] Ibid.