In the past two years, the pace of economic growth in Africa has been decelerating while the political space for democratic contestation has been shrinking. Combined, they can be considered to be major drivers behind the intensifying levels of social unrest throughout the continent. While weaker economic expansion can be principally attributed to global headwinds and inadequate policy responses to exogenous shocks, rising tensions in the political arena emanate from accruing economic hardships and government-led efforts to silence dissent in an environment of growing insecurity.

Across many African countries, labour strikes and boycotts protesting against deteriorating working conditions have multiplied, as have rates of urban crime and riots. Moreover, with a growing number of incumbents attempting to cling on to power via (un)constitutional means, anti-government civic platforms demanding greater democratic accountability have burgeoned. But the heavy-handed response to widespread popular protests in the midst of hotly contested general elections and security backlashes have exacerbated an increasingly acrimonious political environment, with the quashing of opposition groups and civil society organisations (CSOs) adding fuel to the fire.

Although these phenomena are not impacting African countries evenly, those who have been able to weather economic shocks while furthering democratic consolidation are bucking the trend. Should worsening economic conditions and political volatility endure, it will bode ill for the continent’s growth and stability prospects, highlighting the (ostensibly) faltering salience of the “Africa rising” narrative.

Water recedes, rocks appear

The oft-cited factors that have been supporting the high rates of African growth in the past decade have been subsiding since 2014. During the dubbed ‘commodities super-cycle’, high demand and rising prices for African exports propped a continental growth spurt. But the decline in the price of oil and natural gas – as well as minerals, metals and cash crops – has been deflating pan-African growth as a result of dwindling revenue.

Prompted by the emerging markets slowdown, compounded by China’s rebalancing problems and unaided by the sluggish pace of economic recovery in the more economically developed countries, the commodity price slump has had a ripple effect on the African continent. This is principally due to the fact that over 80% of African exports are linked to the commodities sector.[1] The deteriorating terms-of-trade has made it more costly for commodity-dependent economies to import capital and manufactured goods, which remain critical to supporting the fledging levels of industrialisation and infrastructural development across most of the continent.

The ‘commodities super-cycle’ has unravelled in parallel with the tightening of global financial conditions. Unconventional monetary policy in the wake of the ‘Great Recession’ kept interest rates abnormally low, triggering a glut in global financial capital. This made investors thirsty for higher yields, thereby allowing fast-growing African economies to capitalise on rock-bottom borrowing costs.

The recent “Eurobond rush” was the result of an unprecedented number of African governments issuing foreign currency denominated debt. By tapping international capital markets, countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Tanzania have used the proceeds to finance major power-generating and infrastructure projects. The possibility to access a wider pool of international financing constituted an attractive option to boost capital expenditure in areas deemed to enhance economic development at a time when fiscal revenues were starting to decline significantly.

But with the US Federal Reserve progressively raising interest rates, monetary policy normalization at the global level is making investors more risk-averse. With mounting concerns over widening fiscal and current account deficits in countries like Ghana or Zambia, investors are becoming increasingly weary of the weakening debt-servicing capabilities of African governments. Amid rising debt-to-GDP levels and downward pressure on sovereign credit ratings for countries like South Africa and Nigeria, borrowing costs have increased to correct for the higher levels of perceived risk.

With the global environment becoming less favourable, the poorly diversified economies of the continent have taken a significant hit. Reflected by the tumbling value of major commodity-dependent currencies like the South African rand, the Angolan and Zambian kwanza, the Mozambican metical and the Nigerian naira, monetary and fiscal authorities have been struggling to adopt appropriate policy measures. Given the sharp drop in export revenue and the heavy reliance on foreign exchange (FX) reserves to counter the downward pressures on their currencies, state coffers have been largely depleted. Weakened financial firepower has therefore forced some countries to continue issuing debt, with their depreciating currencies not only exacerbating the cost of borrowing, but also stoking price levels through imported inflation. With consumer prices and production costs trending upwards across many African economies, central banks in countries like Algeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Mozambique have been tightening their monetary policy to tame the accelerating rates of inflation.

As governments make greater recourse to domestic financing, private sector credit has been crowded out. This has been worsened by FX shortages, which have caused businesses to either curtail production or close down due to their inability to access hard currency for the purchase of imported inputs. The cases of Egypt, Nigeria and South Sudan are quite telling in this respect. With an overall weakening in economic activity and tumbling government revenue, a majority of African economies have seen their growth rates fall to levels not seen in the past decade.

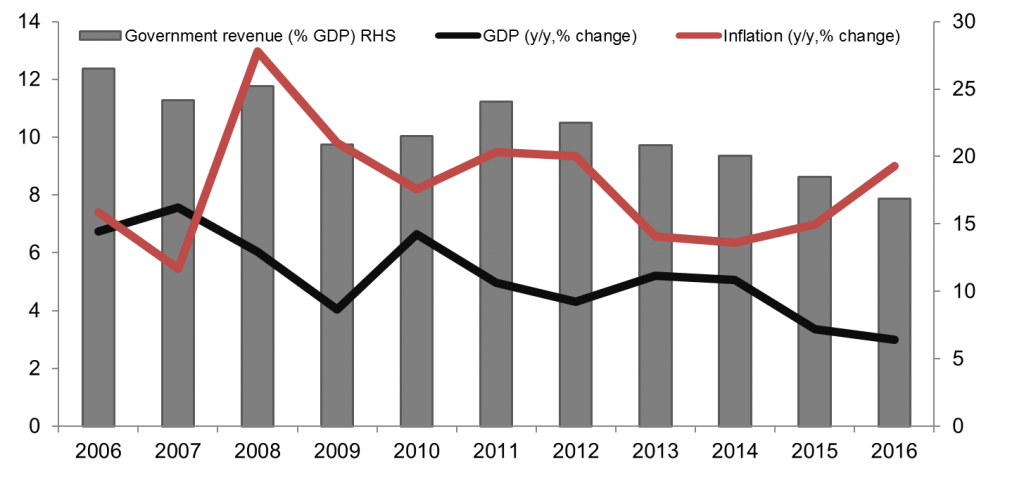

GDP growth, inflation and government revenue in Africa

Data source: IMF (2016). Note: aggregate data for Sub-Saharan Africa only.

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), growth is forecasted to decelerate to 3% this year, down from a 5-7% average between 2010 and 2014. Although countries like Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal are poised to keep their growth rates above 6% in 2017 (supported by strong private consumption, agricultural productivity and infrastructural investment) big economies like South Africa, Nigeria and Angola (which accounted for an estimated 60% of SSA GDP last year) are expected to grow below 3%, possibly even contract.[2] Moreover, eastern and southern African economies like Ethiopia, Malawi and Zimbabwe will be hard-hit by the record-high temperatures and widespread droughts caused by El Niño, while those affected by the Ebola epidemic in West Africa (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone) are yet to witness a pickup in economic activity.

Placing an overt focus on the changes in the global environment could no doubt be misleading. Although it is true that African economies continue to grow at rates above the global average, most of the available evidence is indicative of the fact that adverse conditions in the world economy have prompted an African growth slowdown.[3] Acknowledging that African economies have made encouraging progress in reducing the population share living under $1.25 a day and that there has been a significant decline in the share of the labour force engaged in agriculture (the least productive sector in Africa)[4] –conditions have been worsening for the average African worker. Indeed, depressed salaries and deteriorating working conditions have prevailed at a time when real purchasing power has dwindled, while citizens continue to face security threats – be it from their own governments or at the hands of criminal and violent armed groups.

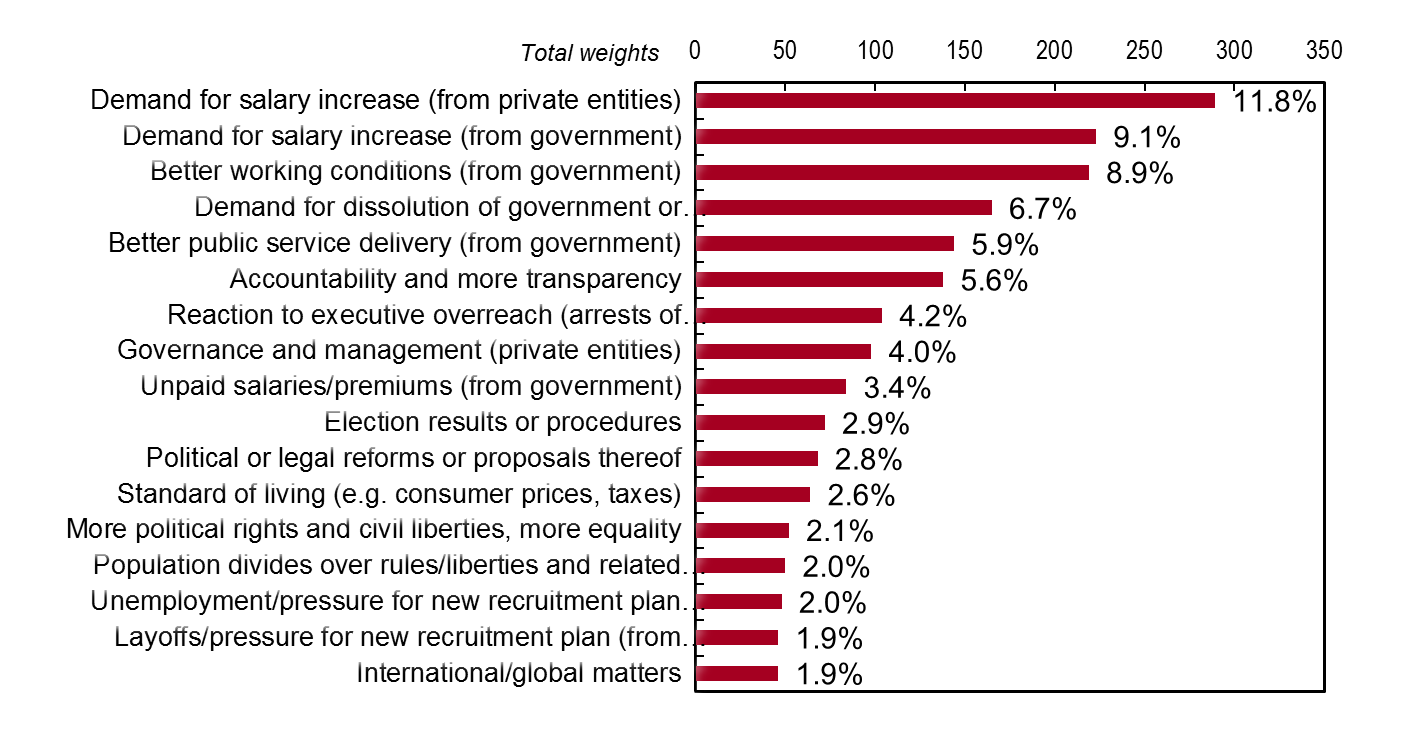

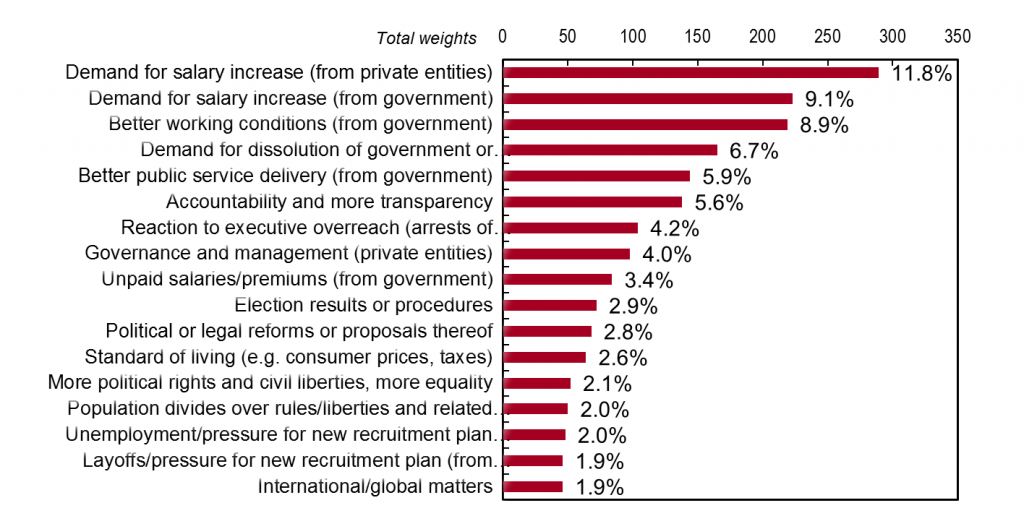

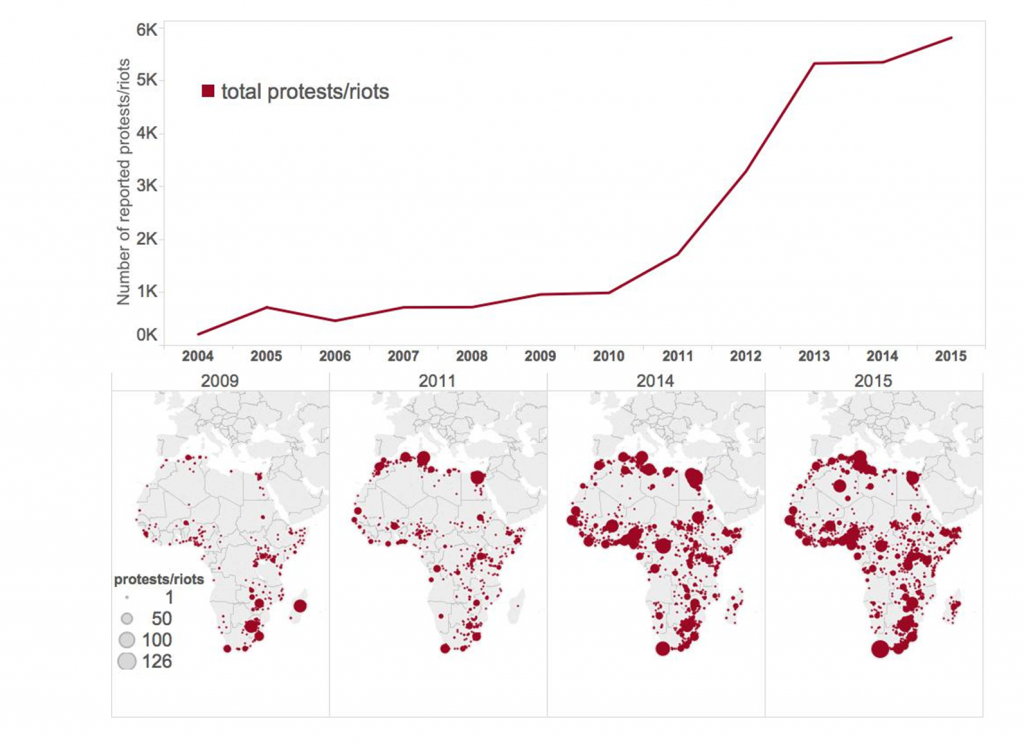

Africa uprising

Against this backdrop, it is easier to understand the catalysts behind the rising number of protests and riots that have erupted in the midst of a busy electoral season, particularly as over three quarters of African countries will have held general elections between 2014 and 2017. In part thanks to better media reporting and increasingly widespread opinion polls carried out by organisations like Afrobarometer, it is possible to gauge the push factors behind the intensifying levels of social unrest across the continent. Indeed, surveys have indicated that among the top motivations for public protests are demands for salary increases and better working conditions, as well as the dissolution of incumbent governments and greater accountability on their behalf.[5]

Top drivers of public protests in Africa

Data source: African Economic Outlook (2016). For details on weights, see statistical annex of AEO report.

As highlighted by the mining sector strikes and university fee protests in South Africa, the textile industry mobilisations in Egypt, the medical doctors’ boycott in South Sudan or the popular uprisings against incumbents in the Great Lakes region: the combination of acute economic hardships mixed with political grievances have buttressed a rising tide of social unrest across the continent. Particularly in the wake of the so-called Arab Spring that led to regime changes in Tunisia and Egypt, popular demonstrations demanding better economic conditions and public service delivery have been multiplying across the continent.

Protests and riots in Africa

Data source: ACLED (2016).

Thwarting democracy

Another phenomenon that has been adding fuel to the fire is the growing (reported) instances of governments using state resources to subdue the activities of opposition parties and CSOs. Across the continent, incumbents have been co-opting the legislature and/or the security forces to abide by their political prerogatives, mainly through patronage networks. By introducing draconian laws or by deploying the armed forces and special police units, governments have been seeking to curtail the activities of political and civil society groups vying for greater democratic accountability. The pre-electoral bans on public demonstrations in Chad and Niger, the mass incarceration of opponents and journalists in Egypt and Ethiopia, police harassment of activists in Uganda and Kenya or the extrajudicial killings reported in Burundi and Congo-Brazzaville all point to a rising trend in “political hardening”, which has been concomitant with higher levels of violent citizen-led protests.

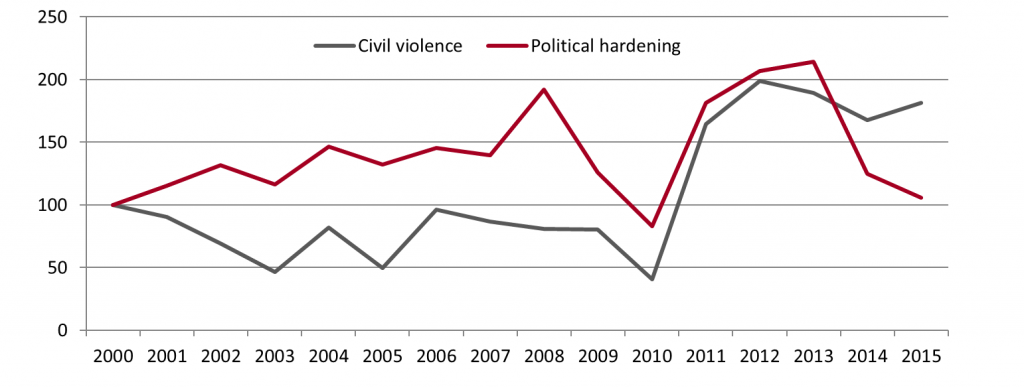

Political hardening and civil violence in Africa

Data source: African Economic Outlook (2016). Note: Indexes with year 2000=100.

In Egypt, Djibouti and Kenya, governments have “securitised” the threat of terrorism and have relied either on executive decrees or on rubber-stamp parliaments to approve vaguely-worded anti-terrorism legislation. This has in turn been used to silence dissenting voices, notably within opposition groups and across media outlets. In Uganda and Congo-Brazzaville, the authorities were able to shutdown social media and other means of communication during their 2016 general elections. This blackout enabled the authorities to mitigate the dissemination of reports unveiling elecrtoral irregularities and voter intimidation, particularly in rural areas. In Niger, Chad and Zanzibar, government repression and allegations of vote-rigging led to the boycotting of polls by opposition groups, which allowed incumbents to consolidate their parliamentary majorities.

Meanwhile, in countries like Burkina Faso, Burundi, the DRC and Congo-Brazzaville, mass demonstrations erupted in protest against their leaders’ intransigence in their determination to prolong their presidential mandates. Their attempts to enforce constitutional changes in order to extend or repeal term limits sparked country-wide protests, which have been met with heavy-handed responses by security forces, particularly in Burundi and the DRC. In the Horn of Africa, the Ethiopian and Sudanese governments have both been violently repressing anti-government activists. While the former has been accused of employing excessive force to crush the Oromia-led protests (which have caused over 400 deaths since November 2015), the latter was heavily criticised by both the African Union (AU) and human rights advocacy groups for the violence perpetrated against political dissenters and students; many of which were reportedly beaten and unduly arrested by police forces throughout the April 2015 general elections.

Insecure Africa

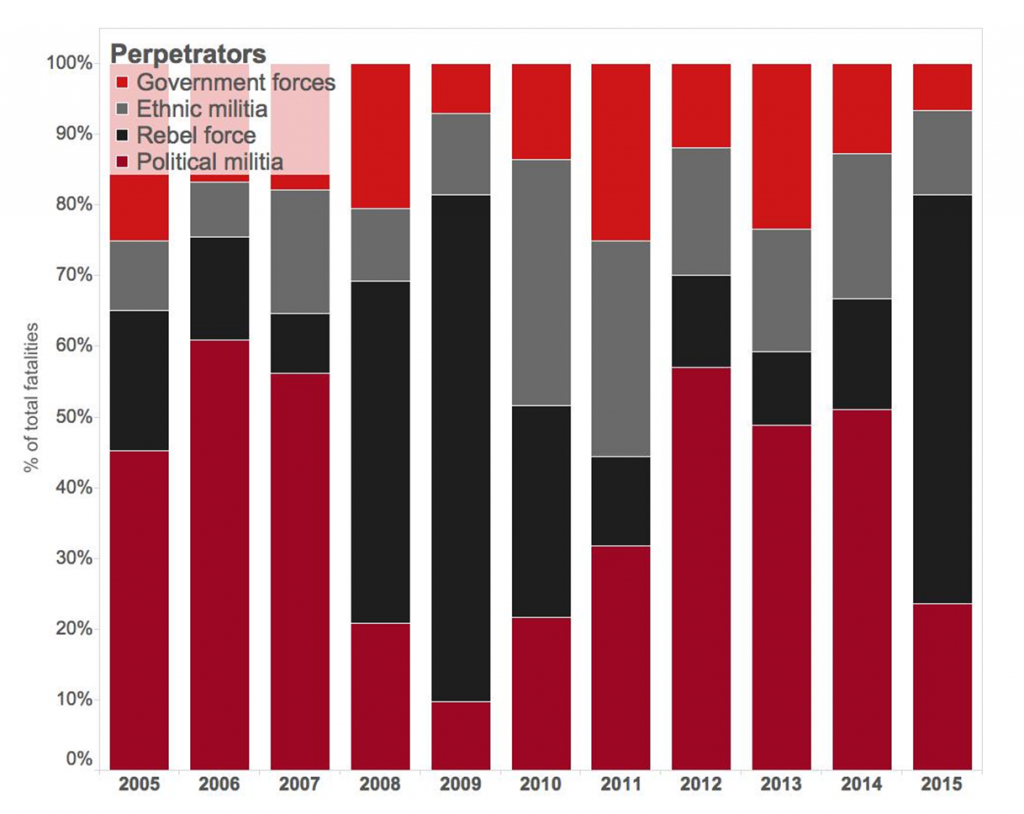

Throughout the particularly intense 2014-2016 electoral calendar, a significant number of sitting presidents across African countries have been egregiously bending the democratic rules to thwart their political competitors, prompting citizens to take to the streets to protest against the abuses of their political representatives, as evidenced by grassroots campaigns such as Le balai citoyen in Burkina Faso or Ca suffit in Chad. This comes at a time when African citizens are facing increasing insecurity at the behest of radicalised armed groups, rebel forces and ethnic militias – particularly as these have become the primary perpetrators of violence against civilians in the past decade.

Violence against civilians in Africa

Data source: ACLED (2016). See ACLED codebook for details on perpetrators.

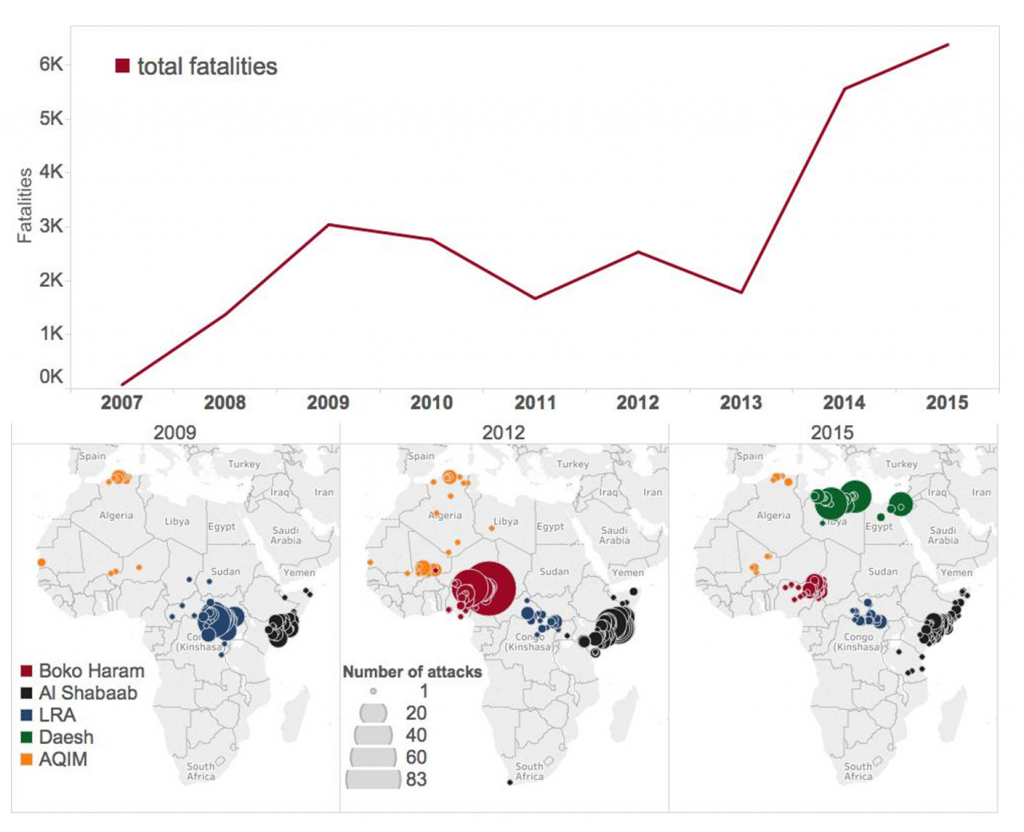

The proliferation and regional expansion of non-state armed groups in the continent remains a source of international concern. In spite of the multinational efforts launched by the Lake Chad Basin countries to fight Boko Haram, or the AU and French-led operations to (respectively) combat Islamist armed groups in the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, terrorist attacks continue to undermine the security landscape across the African sub-regions. Although the United Nations (UN) and US Special Forces have been combining efforts to tame the activities of armed groups in north-eastern DRC and the Lord’s Resistance Army’s (LRA) operations in the Central African Republic, these groups continue to wreak havoc. Moreover, ISIL/Daesh has continued its expansion in North Africa, both through its alliance with the Sinai Province militant group and through its growing control of Libyan territory. Over the last decade, the combined activities of these major African armed groups have resulted in a dramatic increase in the reported fatalities perpetrated by them, both against combatants as well as civilians.

African armed groups

Data source: ACLED (2016). Note: fatalities perpetrated by armed groups.

With the security environment becoming ever so volatile, not only has this adversely affected the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) and forced governments to funnel greater funds into defence and security expenditure, it has fundamentally undermined economic activity and trade. This has been highlighted by the impact that terrorism has had on important FDI destinations like Kenya, Nigeria, Egypt and Tunisia.

Africa rising?

In the past two years, there have been numerous reports that have highlighted the arguably far-fetched nature of the “Africa rising” narrative.[6] In retrospect, the overt focus on the high growth rates across many African countries has little to do with the promise of improved living conditions for the average African citizen. Indeed, GDP growth tells us very little about how incomes are distributed and it certainly does not provide us with a precise indication over how governments capitalised on expanding revenues to invest the proceeds into growth-enhancing activities. It only takes reviewing the Gini coefficients (a measure of national income distribution) across African countries to gauge the extent to which wealth inequalities have persisted throughout the recent period of growth acceleration.

With the largest number of countries in the world ranked at the bottom of the Human Development Index, the African continent hosts 37% of the world’s extreme working poor while 70% of employment on the continent is considered vulnerable.[7] Given Africa’s lack of employment opportunities, volatile business operating environments and lagging progress in improving its revenue-generating capacities, social unrest is likely to continue to act as a drag on growth. This is being exacerbated by wavering investor confidence and eroding purchasing power amid depreciating currencies and exorbitant food prices. As it becomes increasingly clear that the major catalysts behind the African growth spurt were transient and the result of external (as opposed to intra-African) phenomena, it is necessary to question the validity of the “Africa rising” narrative.

To begin with, the jury is still out as to whether African economic growth is being accurately measured. The poorly equipped statistical offices across the continent have been largely inept at accounting for the activities of the informal sector or have only recently been able to quantify the contribution of their fledging telecommunications and financial services industries. This was highlighted by the GDP revisions in Ghana and Nigeria, when their economies “expanded” by 60% and 89% (respectively) as a result of applying new methods of national accounting.

Arguably, this is the result of African authorities’ inability to update their baseline statistics every five years – as per the International Monetary Funds’s (IMF) recommendations – with South Africa being a notable exception. The limitation of budgetary resources destined for national statistics offices has resulted in only a handful of African governments upgrading their accounting methods in the past decade – namely Burundi, Ghana, Malawi, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda and Seychelles. This sheds light on the idea that estimates on African growth are largely based on outdated or inaccurate methods of accounting.[8] The crude takeaway is that we cannot be sure whether Africa is in actual fact rising unless we are willing to have blind faith in the questionable quality of statistics across many African countries.

In sum, recent developments pertaining to setbacks in economic performance and democratic consolidation throughout the continent have highlighted the need to adopt a more nuanced and cautious approach over its future prospects, particularly as the security environment remains unpredictably volatile.

On the economic front, there is a need for greater structural transformation – that is, a shift from the low productivity primary sectors to the higher productivity industrial and service sectors. This would reduce the exposure of commodity-dependent economies to global winds of change, while allowing them to capitalise on economies of scale. In addition, with the middle-class in the vast majority of African countries remaining comparatively small, the ability to mobilise resources through tax collection is still weak.[9] This has forced an increasing number of African governments to pile on their debt as they struggle to keep revenue afloat. Consequently, many have been prompted to call on the IMF for bailouts after a period of (unsustainable) borrowing sprees. This was already the case with Ghana last year and we are now seeing countries undergoing severe debt crises like Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique turning to the ‘lender of last resort’ for urgent help.

As highlighted by the recent (tentative) deal between the IMF and Egypt in which the latter agreed to lend the former a lifeline of $12 billion over three years, African countries with twin deficits, bloated debt levels and depreciating currencies will need to tighten their belts through economic reforms. This however places many African governments between the hammer and the anvil, as imposed austerity on economies with high rates of unemployment is likely to bolster social unrest. This is especially true in a country like Egypt, where a 40% rate of youth joblessness combined with growing shortages of basic goods and active government repression provides fertile ground for political upheaval against growing economic pains.

Politically, an expanding and urbanised youth demographic has become increasingly frustrated with the lack of employment opportunities, as well as with a perceived lack of democratic accountability. This has turned the political landscape in a majority of African countries into an increasingly unstable one. With unwarranted political stability in a fickle security environment; investors, foreign companies and tourists will shy away from pouring much-needed resources into the continent.

Even if Africa’s demographic dividend, expanding consumer markets or growing trade partnerships continue to sustain the continent’s potential to become more integrated within the global economy, much remains to be done for the majority of African economies to escape their poverty traps. Although countries like Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria have been making steady progress in securing their frontier market status, many of their peers remain stuck in low-income status. Most importantly though, few of them have been able to avoid the market jitters caused by the threat of terrorism or social unrest.

With inward FDI to Africa having plummeted by 31% in 2015 alone,[10] many economies that depend on foreign capital and aid to finance infrastructure development or to support fledging economic sectors will continue to drag their feet – lest they find innovative ways to generate greater levels of revenue. This remains a tall order, particularly given the multiplicity of non-economic hindrances to growth (whether geographical, climatic or epidemiological) that are idiosyncratic to the African continent and which continue to place a significant burden on the productivity of its labour force.

Although countries like Botswana and Mauritius continue to exemplify how economic growth can cohabit symbiotically with political stability – and how nations like Cape Verde and Nigeria recently witnessed opposition parties making electoral breakthroughs by democratically replacing incumbent governments – they stand out as continental outliers. With this reality in mind, so long as African economies remain poorly diversified and vulnerable to external shocks while governments continue to tame the mounting voices calling for greater democratic consolidation amid ongoing security threats, cautious optimism may for now be the safest assessment regarding the continent’s future prospects.

Much will depend on the willingness of governments to adopt more prudent and forward-looking macroeconomic policies, while becoming more accommodating to popular demands for greater democratic performance and accountability. This is easier said than done, but it would no doubt lay the ground for a more secure path towards sustained economic growth and political stability in the continent. A good start may be to reconsider the way in which external actors – be they public or private – allocate their technical expertise, financial resources and security or relief assistance, notably in the need for a more humane and long-term commitment.

Endnotes

[1] See World Bank (2015) Africa: end of the commodity super-cycle weighs on growth

[2] See International Monetary Fund (2016) Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See McMillan, M. & Harttgen, K. (2014) ‘What is Driving the ‘African Growth Miracle?’ African Development Bank Group, Working Paper Series no. 209

[5] See African Economic Outlook (2016) for compilation of surveys on public protests.

[6] See Rodrik, D. (2014) ‘An African Growth Miracle?’, Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton or Morten Jerven (2013) Poor numbers: how we are misled by African Development Statistics and what we can do about it. Cornell University Press.

[7] See International Labour Organisation, Global Employment Trends 2014.

[8] See Morten Jerven (2013) Poor numbers: how we are misled by African Development Statistics and what we can do about it. Cornell University Press.

[9] Although a handful of African countries (Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritius, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa and Tunisia) are reported to be making progress in increasing their tax-to-GDP ratios, see OECD “Rising tax revenues are key to economic development in African countries”, 1 April 2016.

[10] See UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2015.