Since 2015, the DR Congo, a major rent-based economy in Africa, has embarked into macroeconomic turbulence with significant inflationary pressures and a severe exchange rate depression, partly due to a commodities slump. The economic downturn has contributed to strengthening the acute social crisis. The country is a fragile state on the edge, a product of the postponement of the 2016 presidential elections.

Altogether, the country’s socioeconomic governance is in jeopardy. This paper proposes to examine the root causes of macroeconomic uncertainty in the DR Congo. It investigates how uncertainty has generated a negative impact on key macroeconomic indicators, including real GDP growth rate and inflation. Main features of the country’s economy are assessed on a basis of the Central Bank of Congo and IMF data. The findings reveal that uncertainty is strongly related to commodity prices’ volatility. On the domestic front, sustained macroeconomic uncertainty is further stimulated by political instability, combined with rising insecurity in the eastern and western provinces. Overall, external and internal shocks have affected the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy.

As a result, the government’s margins of maneuver are extremely reduced. As part of crisis recovery strategies, a critical policy recommendation suggests the implementation of the political agreement of December 31st, 2016, which was negotiated between the ruling party and the opposition, to resolve the current political impasse.

Introduction

Despite its rich endowment of natural resources, the DR Congo remains primarily a commodity export economy. In 2001, after the end of the 1998-2003 second Congolese war, a donors’ community gradually cooperated with the DR Congo. From 2004 to 2014, the country experienced relative macroeconomic stability. In 2015, its economic resilience deteriorated. Since then, the country has been going through major macroeconomic turbulence.

First, the paper examines the country’s fragile economic resilience, as its economic performance is closely tied to the fluctuation of commodities prices.

Second, the paper reviews key features of the economic downturn. It refers to macroeconomic developments covering December 2014 to August 2017. Given macroeconomic imbalances, it analyzes a set of measures elaborated by the Congolese authorities and the Banque Centrale du Congo (BCC) to reinforce macroeconomic policies’ coordination in a highly dollarized economy.

Third, the paper identifies political turmoil and security concerns as major contributing factors to macroeconomic uncertainty in the DR Congo. In response, an inclusive mediation process was initiated to restore relative political stability. As a result, the December 31st, 2016 agreement was concluded. Nonetheless, it was not implemented in a timely manner. It did not lay the foundation for a peaceful political transition. Consequently, political uncertainty puts macroeconomic developments in the DR Congo further in jeopardy.

- The DR Congo: A Fragile Economic Resilience

The DR Congo concentrates about 10% and 30% in the ex-Katanga province[i] in South-Eastern DR Congo. Its economy heavily depends on the exports of the above-mentioned commodities. Therefore, it remains extremely vulnerable to external shocks, including drops in global commodity prices in 2007 and 2015. These shocks entailed macroeconomic disorders.

1.1. From the Impact of the International Financial Crisis to the Commodities Slump

In 2007, the global financial crisis generated a depression in commodity markets. The DR Congo experienced a severe mining crisis, notably in the copper-cobalt belt of the ex-Katanga province. Beyond a drastic reduction of export revenues, the crisis negatively impacted on the country’s economy.

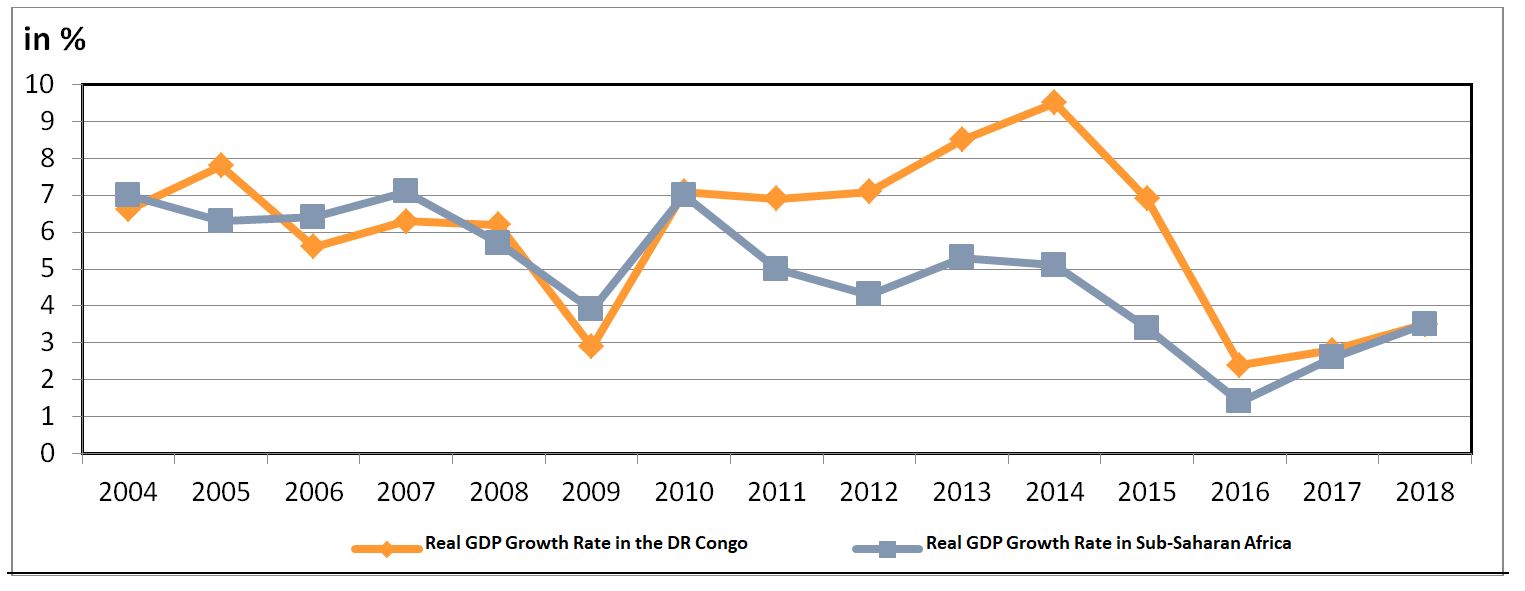

As of 2015, a second mining crisis occurred in the DR Congo, resulting from a drop in global commodity prices. In terms of trade balance, the country’s exports dropped USD 10,293,164 942.77 to USD 12,311,036,836.25. In 20I5, mineral and oil exports corresponded to 97.5% of the country’s total export value. Mineral exports included copper, cobalt, and zinc from Gecamines and partners operating in the above-mentioned copper-cobalt belt. They represented 80.7% of the country’s total export value (Figure 1).

–

Figure 1. Structure of Exports of the DR Congo in 2015

Source: The author on the basis of the Banque Centrale du Congo (2015), Rapport annuel, pp. 1-336.

–

In 2015, China was the first trade partner of the country. The geopolitics of copper and cobalt led China to strengthen its economic partnership with the DR Congo. In addition to the Sino-Congolese mining deal of 2007[ii], it increased its presence in the country, through major mining acquisitions over the last decade[iii]. Macroeconomic developments in China will continue to impact the Congolese economy.

Overall, improving governance of the extractive sector remains a prerequisite. The sector is a major source of country’s growth potential. This promises to improve the legal framework pertaining to the business environment, including the long overdue review of the 2002 mining code[iv]. Additionally, the DR Congo has to engage in economic diversification by developing the agribusiness sector, which will require the implementation of structural reforms[v]. It is confronted with a deficit in infrastructure (transportation and energy supplies) despite its strategic location in Central Africa. The aforementioned reforms will enable the DR Congo to move towards sustainable economic development and poverty alleviation.

1.2. Aftermath of Commodity Price Volatility in the DR Congo

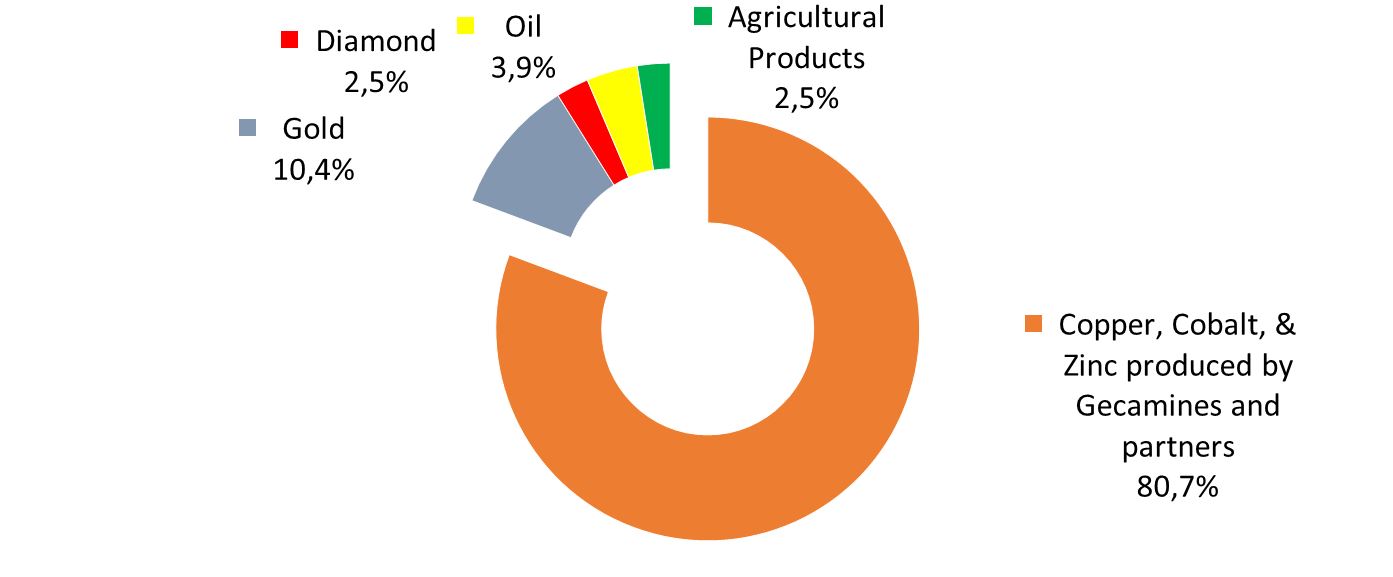

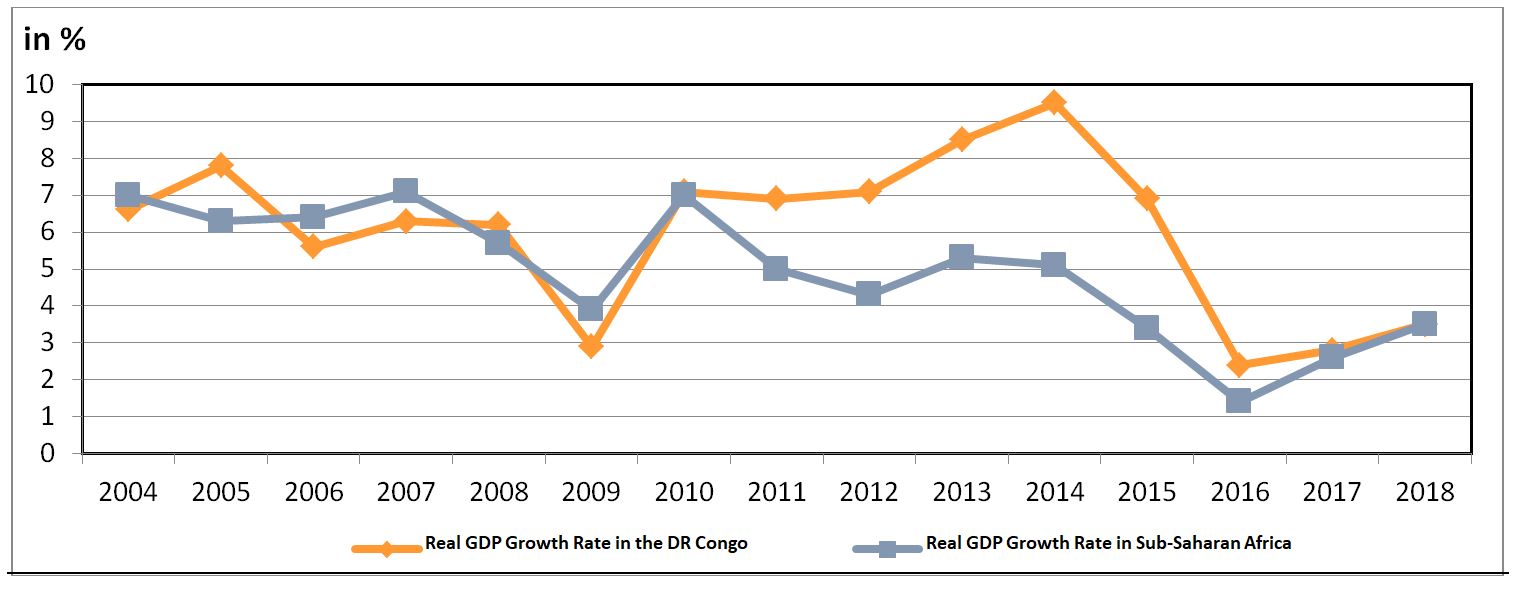

From 2004 to 2007, Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate slightly decreased from 6.6% to 6.3%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). From 2008 to 2009, it fell from 6.2% to 2.9%, owing to the impact of the global financial crisis of 2007. As a result, the country entered into its first recession in September 2008[vi].

Nevertheless, from 2010 to 2013, real GDP growth rose from 7.1% to 8.5%. In 2014, it was estimated at 9.2%, which was the third fastest growth rate in the world. The primary sector (40.6% of GDP) including the extractive industries (22% of GDP), the secondary sector (20.9%), and the tertiary sector (31% of GDP) drove the economic growth.

Overall, the DR Congo experienced relative macroeconomic stability from 2004 to 2014, although it was confronted with an acute social crisis combined with a longstanding humanitarian crisis throughout the country.

As of mid-2015, the country was severely impacted by a drop in prices of its major export commodities[vii] due to China’s economic slowdown[viii]. The commodities slump revealed the first warning signs of the economic downturn. Real GDP growth rate declined from 6.9% to 2.4% from 2015 to 2016.

Real GDP growth is projected at 2.8% and 3.5%, respectively, in 2017 and 2018 (Figure 2). The DR Congo could potentially achieve these projections given the positive trend observed in commodities markets. The development of clean energy technologies, including the dynamic electric car market, has contributed to a higher demand for copper, cobalt, and lithium. However, the realization of the said projections will depend on the future of the political regime.

–

Figure 2. Evolution of the Real GDP Rates in the DR Congo and Sub-Saharan Africa from 2004 to 2018

Source: The author on the basis of the IMF (2017), The Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, Restarting the Growth Engine, April, pp.1-111 & IMF (2013), The Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, Keeping the Pace, October, pp. 1-116.

–

- A Dollarized Economy in a Tailspin during Political Transition

Since 2015, efforts to extend the unstable political regime have plunged the country into yet another political transition since its independence in 1960. This has contributed to a worsening of the country’s macroeconomic developments. Since then, the successive governments and the BCC have tried to implement measures to curb negative economic and financial trends. However, this leads to questions regarding the ability of Congolese authorities and policymakers to improve the country’s economic governance amid the political turmoil.

2.1. Unprecedented Pressures on Monetary Policy

The country’s economy has entered a zone of turbulence. Its vulnerability to external shocks has precipitated increasing inflationary pressures. It has also entailed a crisis of confidence in the national currency. In these circumstances, the central bank plays a critical role. It is committed to reducing inflation and defending the national currency by conducting a restrictive monetary policy. However, enforcing its mandate is a complex prospect in a highly dollarized economy facing an uncertain political transition.

2.1.1. The DR Congo Renewing with Inflationary Spiral

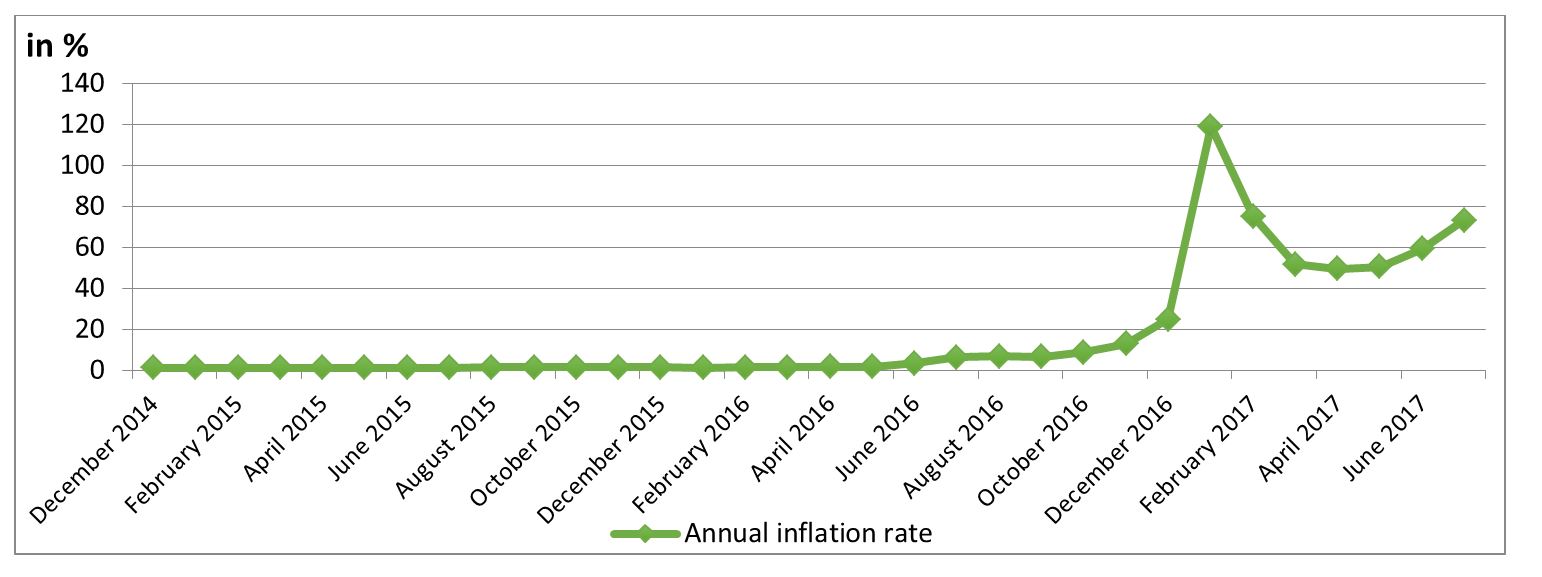

From December 31st, 2014 to June 29th, 2016, the annual inflation increased from 1.26% to 3.44%. From July 29th to December 31st, 2016, it soared from 6.5% to 25.04%, regardless of the first set of the government’s measures having been implemented on January 28th, 2016. On January 31st, 2017, it spiked to 119.13%, the highest for the first time in eight years. From February 28th to July 16th, 2017, annual inflation slightly decreased, from 75.13% to 73.23%, although it remained above 50% (see Figure 3). Regardless of its agricultural potential, the DR Congo is a major importer of food products, which continues to fuel inflationary pressures. Altogether, it has experienced hyperinflation, which is, to a lesser extent, a reminder of Zaire’s hyperinflation crisis, which occurred from 1990 to 1996[ix]. Besides the external shocks, the main causes of the hyperinflation are political in nature. Rising political instability was exclusively derived from the over-delayed presidential elections.

Figure 3. Evolution of the Annual Inflation Rate in the DR Congo from December 2014 to July 2017*

Source: The author on the basis the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2015), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, Condensé Hebdomadaire d’Informations Statistiques au 21 juillet, 26 juillet, n°29 /2017.

Note : (*) 23 July 2017.

–

2.1.2. Crisis of Confidence in the Congolese Franc

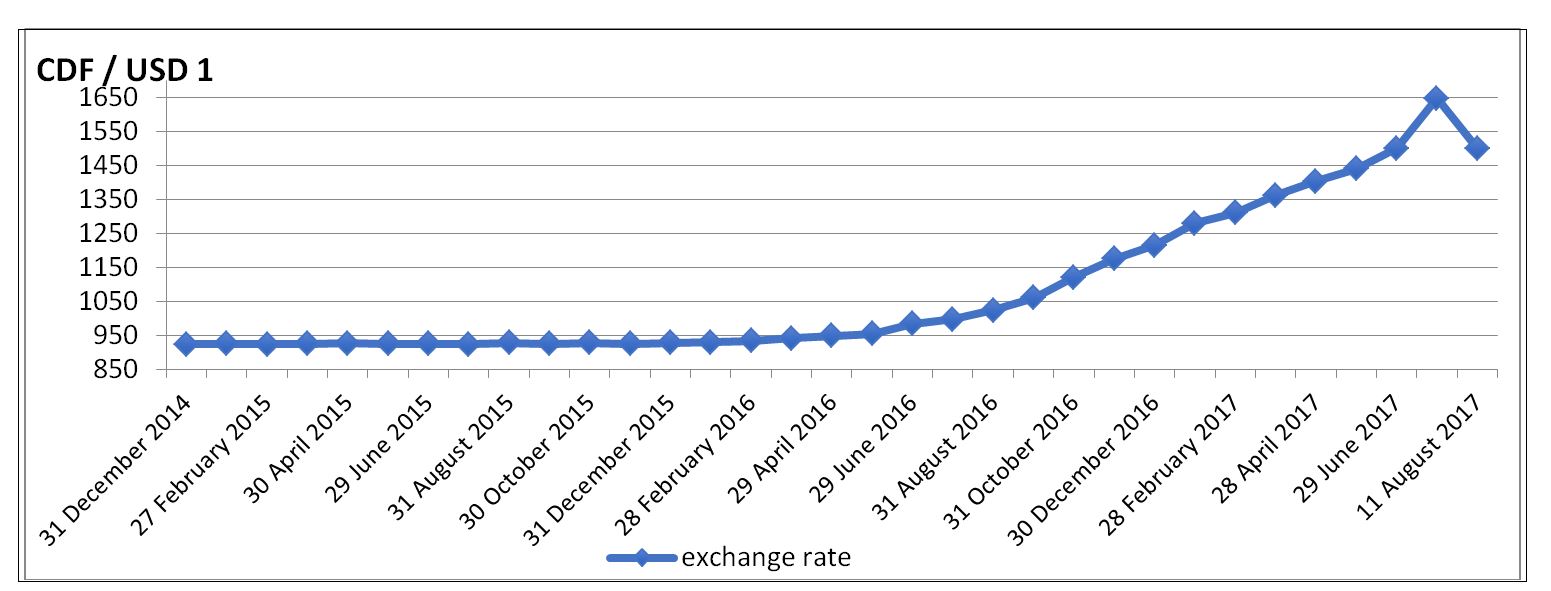

The inflationary spiral has put pressure on the official exchange rate of the freely floating Congo Franc (CDF) against the US Dollar (USD). From December 31st, 2015 to December 30th, 2016, the Congolese franc depreciated against the USD, from CDF 927.92 per USD 1 to CDF 1,215.59 per USD, corresponding to a 31% monetary depreciation. On January 31st, 2017, the national currency depreciated from CDF 927.92 per USD to reach CDF 1,647.80 by end July 2017, or a depreciation of 28.67% in seven months (Figure 4). As a result, Congolese households’ purchasing power continued to drop. This led to mounting social tension, including repeated calls for strikes[x]. The Congolese currency’s depreciation damaged economic operators’ confidence. A higher country-risk resulted from a deterioration of the business climate. Since the end of July 2017, the Congolese currency has timidly appreciated against the American currency[xi]. On August 11th, 2017, it was traded at CDF 1,500.56 / USD 1.

Figure 4. Evolution of the Official Exchange Rate from December 2014 to August 2017*

Source: The author on the basis of the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2015), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, the Banque Centrale du Congo (2017), Condensé Hebdomadaire d’Informations Statistiques au 21 juillet, 26 juillet, n°29 /2017, and the BCC website, 11 August 2017.

Note : (*) 11 August 2017.

–

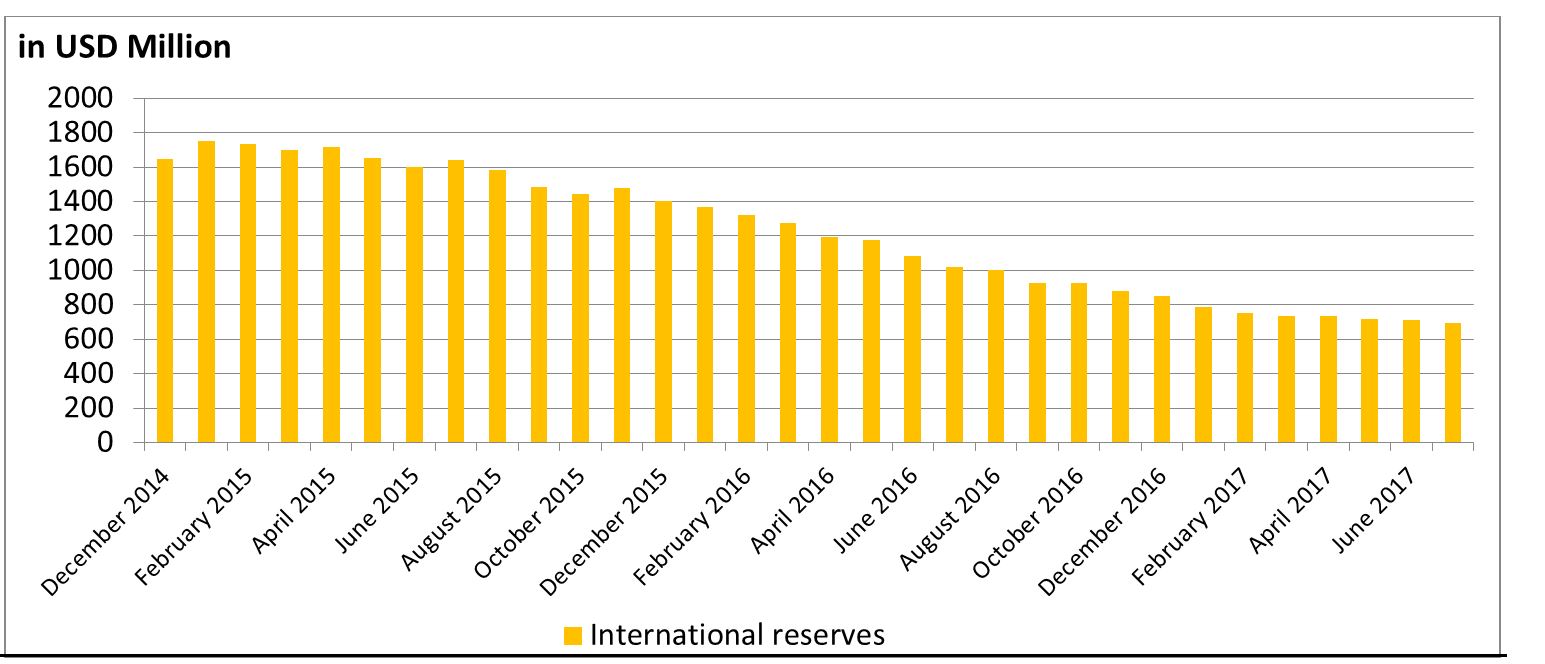

2.1.3. Critical Threshold of the International Reserves

The Congolese franc has lost considerable value alongside the USD. This also showed difficulties that the BCC faced in maintaining its international reserves. From December 2014 to June 2016, the central bank’s gross international reserves decreased from USD 1,644.48 million to USD 1,091.28 million, mainly owing to a drop in export of commodities. From September 30th to December 30th, 2016, they continued to fall, from USD 928.24 million to USD 852.14 million, corresponding to 3.76 weeks of imports. On September 30th, 2016, they amounted to USD 928.24 million. On July 20th, 2017, they were only estimated at USD 693.80 million or 3.05 weeks of imports (Figure 5).

On July 17th, 2017, the central bank requested the enforcement of a measure related to the repatriation of at least 40% of mining companies’ revenues from mineral exports, to lessen the shortage of foreign exchange. The non-compliance of the said measure will generate penalties. Alone, the implementation of this measure will be insufficient to mitigate the erosion of the BCC’s gross international reserves. The crisis of confidence in the Congolese franc has undermined its central bank’s credibility.

–

Figure 5. Evolution of the International Reserves from December 2014 to July 2017*

Source: The author on the basis of the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2015), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, and the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2017), Condensé Hebdomadaire d’Informations Statistiques au 21 juillet, 26 juillet, n°29 /2017.

Note : (*) 20 July 2017.

–

2.1.4. The Central Bank under Scrutiny

In principle, law n°005/2002 of May 7th, 2002[xii] granted the central bank’s independence in order to depoliticize the conduct of the monetary policy and achieve price stability. Under the impulse of the monetary policy committee, the BCC has tried to immediately respond to the continued deterioration of the country’s macroeconomic framework since 2015.

On September 28th, 2016, the monetary institution raised its principal interest rate from 5% to 7%. On June 26th, 2017, it continued to increase the said rate from 14% to 20%, to halt a drop in foreign reserves and severe depreciation of the national currency against American currency. Second, the central bank has used its own liquidity management tool, known as the “Billets de Trésorerie” (BTR), to regulate base money. Since 2016, the exchange rate has remained volatile, despite several foreign exchange auctions to extract liquidity.

In practice, the central bank has faced tremendous difficulties in attempting to tighten its monetary policy. Over the years, it has lost control over monetary policy instruments in a highly dollarized economy[xiii]. In mid-1990 and 2001, the dollarization ratio was estimated at 90% and 75%, respectively[xiv]. In 2014, the dollarization process was estimated at 85% of total deposits in USD in banks and 174% of gross international reserves[xv]. As a result, the effectiveness of the BCC’s monetary policy is extremely restricted. Also, the BCC has operated in a fragile state, characterized by weak institutions.

2.2. Public Finance in Crisis

As the country degenerated into political turmoil in 2015, successive governments have undermined the central bank’s independence by implementing unsustainable fiscal policies. A lack of coordination of monetary and fiscal policies showed that fiscal policy became dominant over monetary policy. The central bank was constrained to monetize budget deficits.

2.2.1. Concerns over Conduct of Fiscal Policy

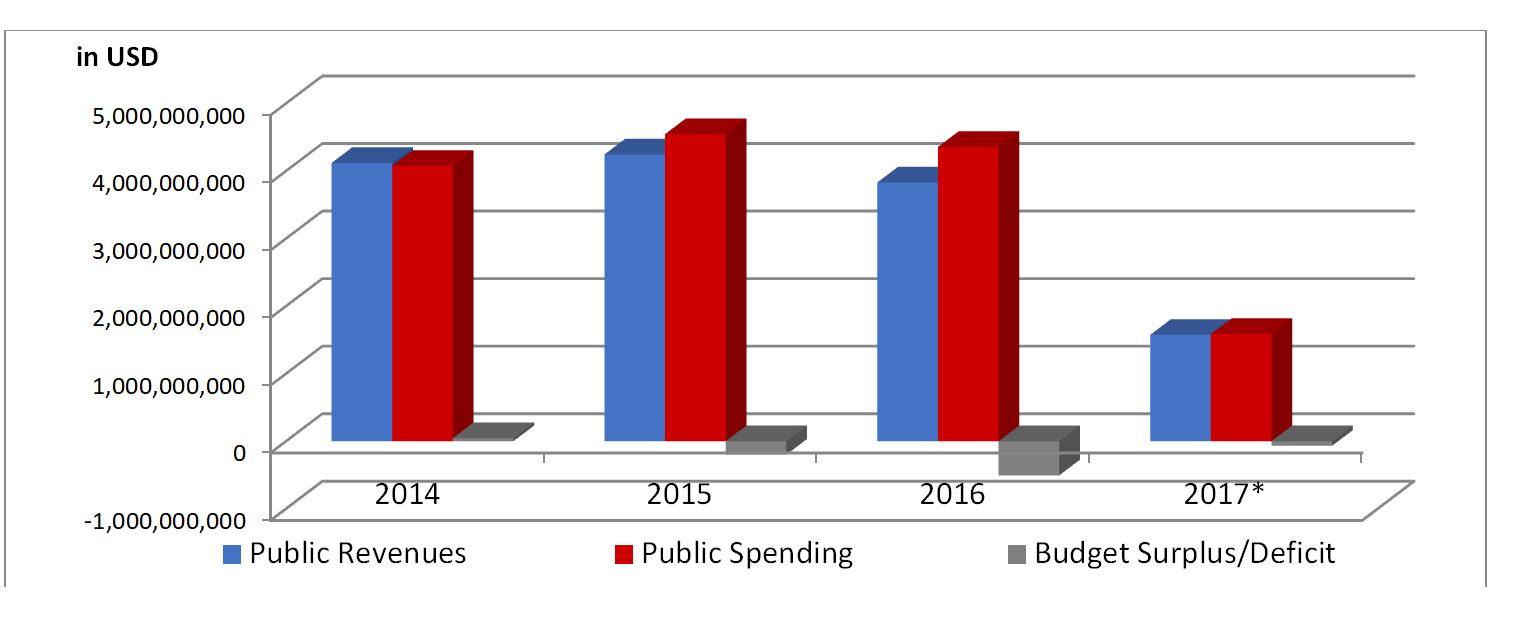

In 2014, the country recorded a budget surplus amounting to USD 44,259,277.15. Since 2015, a sharp drop in commodities prices has negatively impacted public finance. In 2015, the annual budget deficit accounted for USD 506,372,167 from 2015 to 2016. In early 2016, the government implemented 28 emergency measures to address macroeconomic imbalances. However, these measures were insufficient. As a result, on May 4th, 2016, the government revised the 2016 State budget, from USD 9.080.681.622 to USD 6.800.000.000, given its limited capacity to mobilize domestic revenue. The initial State budget, which was cut by 22%, was promulgated on June 29th, 2016[xvi].

On October 24th, 2016, the then government submitted the 2017 draft State budget of USD 4.500.000.000 to the national assembly. The examination of the said draft budget was suspended, while the country experienced rising political turmoil.

At the end 2016, the annual budget deficit increased by USD 200,264,449.9. Budget slippages mainly resulted from a tense political situation, coupled with growing security concerns in the eastern provinces and in the Kasai region. Also, they revealed a weakness in terms of expenditure management procedure; notably the expenditure chain. In this context, the central bank acknowledged that it monetized budget deficits[xvii], which increased monetary supply. Also, this contributed to fueling continued monetary depreciation associated with an inflationary spiral. Since the country’s independence in June 1960, government deficits have often been financed through money creation, particularly during political instability[xviii], and in particular under the Mobutu regime[xix].

As of January 1st, 2017, the country officially embarked on a political transition, as stipulated in the political agreement dated December 31st, 2016. Delays in examining the 2017 State budget entailed executing the provisional credits on a monthly basis. Following the installment of the transitional government, a revised 2017 draft State budget was resubmitted to the Parliament. On June 29th, 2017, President Kabila promulgated the 2017 State budget of USD 8,085,949.83, with a six-month delay. Key budgetary priorities focused on funding the electoral cycle[xx] and sovereignty-related spending, owing to the security crisis in the eastern provinces and the Kasaï region.

From January 1st, 2016 to July 27th, 2017, the transitional government attempted to restore a fragile fiscal discipline. It limited public expenditures, without necessarily strengthening public spending tracking. Also, it delayed the execution of public spending, including civil servants’ salaries (Figure 6). Such decision has increased social tensions in a country already confronted with an acute social crisis. Moreover, the unexpected public spending related to the electoral process and insecurity constitutes a serious matter of concern. To prevent budgetary slippages, a strict monitoring of public finance will be critical during the transitional period leading up to the next elections.

–

Figure 6. Execution of the State Budgets and the Provisional Credits from 2014 to July 2017

Source: The author on the basis of the Banque Centrale du Congo, (2017), Condensé Hebdomadaire d’Informations Statistiques, n°29 du 21 juillet, pp. 1-44 & Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Mensuel d’Informations Statistiques – février 2016, 15 mars, pp. 1-82.

–

Furthermore, the transitional government is committed to raising public revenues. On August 12th, 2017, it temporarily suspended VAT exemption on imports for mining companies operating in the country[xxi]. It plans to improve Domestic Revenue Mobilization (DRM) by increasing its tax base. This will require key structural reforms, which will be governance challenges. These reforms comprise: (i) rebuilding fiscal institutions (tax and customs administrations) at the national and provincial levels; (ii) fighting against Illicit Financial Flows[xxii]; and (iii) proceeding to the country’s economic diversification.

2.2.2. The DR Congo: In Search for Donors’ Assistance

In the aftermath of the commodities slump in 2015-2016, some rent-based economies, including Nigeria and Suriname, requested the IMF’s financial assistance. The DR Congo’s last three-year economic program[xxiii] with the IMF ended in December 2012. Since then, the IMF has maintained a policy dialogue and technical assistance with the country. In 2015, the IMF and the DR Congo restarted official discussions for a new economic program under article 4, wherein the country has entered into a deep economic crisis. Finally, on June 12th, 2017, the transitional government sought financial assistance from the IMF under the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) to deal with an urgent balance of payments need amid a critical political impasse[xxiv]. In response, on June 29th, 2017, the IMF conditioned financial support under tangible political progress. An IMF delegation was expected to visit the country to assess the economic situation as of mid-September 2017. It could be challenging for the IMF and the DR Congo to conclude a new economic program given mounting political uncertainty. It is worth noting that, in 2009, the country received the IMF’s assistance to address the impact of the international financial crisis on the balance of payment[xxv] and to stabilize the national currency. Overall, the DR Congo has regularly called upon the Bretton Woods institutions, including the IMF, to gradually replenish its international reserves[xxvi].

- Economy in Jeopardy: Focus on Political and Security Factors

A deficit in institution building and the restoration of state authority both constitute internal shocks. These shocks fueled macroeconomic uncertainty in the DR Congo. First, the end of Mobutu’s political regime generated several years of conflict. From 2003 to 2014, the DR Congo engaged in efforts towards building a legitimate state apparatus with donors’ support. Then the 2006 and 2011 presidential elections legitimated the emerging political regime. In 2015, the political landscape gradually deteriorated in the run-up to a new electoral cycle. Nevertheless, the postponement of the 2016 presidential elections entailed a political impasse. Second, the DR Congo remains confronted with the restoration of state authority. A major security crisis spread throughout the country.

3.1. Attempts at Solving Political Impasse in the DR Congo on the Edge

In 2015, the DR Congo experienced its first major political crisis since the 1998-2003 second Congolese war. A year later, the African Union (AU) and the Congolese Catholic Church (CENCO) launched two international and national mediation processes. However, these initiatives did not record major political progress.

3.1.1. The DR Congo facing Political and Electoral Crises

The electoral crisis combined with the constitutional crisis has resulted in political turmoil. Referring to the constitutional court decision dated May 11th, 2016, President Kabila will remain in office until the installation of the newly-elected president. In September 2016, the AU led the first national mediation in hopes to diffuse warning signs of a political crisis. On October 18th, 2016, the AU-facilitated agreement authorized a delay in the 2016 presidential election until April 2018. The opposition contested the agreement, considering that President Joseph Kabila’s second term and last mandate ended on December 19th, 2016. A worsening political situation created widespread violence.

On December 8th, 2016, the CENCO conducted a second mediation process including the ruling party and the opposition. On December 31st, 2016, it concluded with an agreement providing an institutional framework during the political transition[xxvii]. According to said agreement, President Kabila would remain in office until December, 31st, 2017. Meanwhile, the provincial, national, and presidential elections would take place no later than December 31st, 2017. The transitional government’s installment would ensure the national cohesion. All institutions would continue their mandates on an interim basis. A Conseil National de Suivi de l’Accord (CNSA), an oversight institution, would also be set up to monitor the implementation of the December 31st, 2016 agreement. Beyond the aforementioned agreement, the main challenges would consist of building trust in the electoral process during the transition.

3.1.2. Aftermath of the Implementation of the Agreement of December 31st, 2016

The opposition, the CENCO, and the donors’ community, including the United Nations (UN) and the Council of the European Union (EU)[xxviii], repeatedly called for action to comply with and fully implement the December 31st, 2016 agreement. Given a political ownership deficiency related to the implementation of the said agreement, on March 27th, 2017, the CENCO withdrew its involvement from mediation efforts. So far, major milestones are as follows:

– On April 7th, 2017, President Kabila appointed Mr. Bruno Tshibala as Prime Minister during the political transition. On May 9th, 2017, the Tshibala government was mainly comprised of ministers and members of the ruling party.

– On July 25th, 2017, the transitional government appointed Mr. Joseph Olenghankoy, the chair of the CNSA, and other CNSA members. The opposition and the civil society, however, contested the CNSA presidency, revealing a strong political defiance.

– In preparation for the presidential elections, in August 2017, the CENI continues voter enrollment in the tumultuous Kasaï region.

Beyond voter registration, the presidential election’s timetable is a major concern. The UN, the EU, the CENCO, and the opposition called for holding the presidential elections no later than December 31st, 2017 in line with the December 31st, 2016 agreement. On July 7th, 2017, the CENI announced that the presidential elections would not take place in 2017, given that the Kasai region was in crisis. The ruling party and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) supported the CENI’s decision, while the opposition and the donors’ community denounced it. On July 10th, 2017, the CENCO consulted with the transitional government, the CENI, and the CNSA to decide on the future of the presidential election organization. The late publication of the electoral calendar crystallized rising political tensions. The December 31st, 2016 agreement did not lay the foundation for a peaceful political transition. The prolonged political crisis shows how the derailment of the December 31st, 2016 agreement could jeopardize donors’ confidence, including the IMF.

Finally, on November 5th, 2017, the CENI announced the organization of the presidential, legislative, and provincial elections on December 23rd, 2018[xxix]. The swearing-in ceremony of the president-elect will take place on January 12th, 2019. The opposition largely rejected the electoral calendar. This has sparked another spiral of violence in various cities, such as Goma, Lubumbashi, Kindu, and Beni. Since 2015, the country has regularly embarked in large scale violence[xxx] due to the political crises resulting from the electoral crises.

Overall, political uncertainty keeps deepening, along with waves of violent demonstrations throughout the country. There is high risk of a postponement of the presidential elections. The DR Congo has never experienced a peaceful transfer of power since its independence in 1960.

3.2. A Rising Insecurity in the DR Congo in Crisis

In connection with political regime instability, the DR Congo has recorded critical security challenges in the Eastern DR Congo, particularly in five provinces (North Kivu, South Kivu, Ituri, and Tanganyika). Furthermore, widespread violence has emerged in the Western DR Congo, comprising six provinces of the Kasaï region (Kasai, Kasai Central, Kasai Oriental, Lomami, Sankuru, and Kwilu), since August 2016.

3.2.1. A Longstanding Security Crisis in Eastern DR Congo

Since June 2003, the DR Congo has made some progress in the economic reunification process. It has embarked on a transition from a war economy to a peace economy, except in the eastern provinces. It is committed to pacifying the eastern side of the country with the assistance of the donors’ community. Over the last decade, the national army, the so-called Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC), and the UN peacekeeping mission have launched a series of joint military operations against militias, including Rudia II in South Irumu, Iron Stone, Umoja Wetu, and Kimia II, to restore the state authority. Nonetheless, insecurity still prevails in Eastern DR Congo, notably Beni (North Kivu) and Kalemie (Tanganyika province). It has put a heavy pressure on public finance over the years.

3.2.2. Emergence of Insecurity in Western DR Congo: From the Kasaï Region and Other Western Provinces

As of August 2016, a major security crisis has erupted in the Kasaï region under the impulse of militia, such as the Kamuina Nsapu, the Bana Mura, and the FARDC. A year later, volatile security situations still persist as militias are not yet dismantled. The Kasaï in crisis has generated a major humanitarian crisis, combined with a migration crisis. As a result, 1.3 million of people were internally displaced from April to June 22nd, 2017. Moreover, acts of violence are observed in other western provinces, such as Matadi (Kongo Central province) and Kinshasa in 2017. They entailed a surge in sovereignty-related spending.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Major risks to the country’s economic outlook for 2018 are closely associated with uncertainty due to a multidimensional crisis. The transitional government is, therefore, exposed to higher macroeconomic risks. Although its margins of maneuver are extremely reduced, its priority consists in restoring a fiscal discipline. In this connection, the central bank should preserve its independence to conduct a monetary policy in a highly dollarized economy.

The DR Congo has the potential to become a driving force in terms of regional growth. In this context, its economy could benefit from a surge in prices observed in key commodities markets, such as cobalt and copper. The macroeconomic stabilization closely depends on the country’s political landscape. Nonetheless, a chronic deficit in institution building and the restoration of state’s authority in the eastern provinces and the Kasai region constitute major obstacles to the country’s economic resilience.

Beyond the publication of the electoral calendar in November 2017, a critical policy recommendation might suggest reviewing the political agreement of December 31st, 2016 to resolve the current political impasse. Moving towards a sustainable political stability is a key prerequisite for sustained growth and inclusive development.

Bibliography

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2015), Rapport annuel, pp. 1-336,

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2017), Communiqué, Comité de Politique Monétaire, 4 août, pp. 1-3,

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2017), Condensé Hebdomadaire d’Informations Statistiques, n°29 du 21 juillet, pp. 1-44,

http://www.bcc.cd/downloads/pub/condinfostat/Con_Info_Stat_29_2017.pdf

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Mensuel d’Informations Statistiques – février 2016, 15 mars, pp. 1-82, http://www.bcc.cd/downloads/pub/bulstat/bul_stat_fev_2016.pdf

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2016), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, see http : www.bcc.cd

Banque Centrale du Congo, (2015), Bulletins Mensuels d’Informations Statistiques de janvier à décembre, pp. 1-80, see http : www.bcc.cd

Banque Mondiale, (2015), Rapport de Suivi de la Situation Economique et Financière de 2015, septembre, pp. 1-57,

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/698271467998198/pdf/99991-FRENCH-WP-P151615-PUBLIC-Box393216B.pdf

Beaugrand P. (1997), Zaïre Hyperinflation, IMF Working Paper n° 97/50, April 1st, pp. 1-39, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/wp9750.pdf

Beaugrand P., (2003), Overshooting and Dollarization in the Democratic Republic of Congo, IMF Working Paper n°03/105, pp. 1-27.

CENI, (2017), Calendrier électoral : Décision n°065/CENI/BUR/17 du 05 Novembre portant publication des élections présidentielles, législatives, provinciales, urbaines, municipales et locales, http://www.ceni.cd/assets/bundles/documents/calendrier-electoral-decision-n065-ceni-bur-17-du-05-novembre-2017-portant-publication-du-calendrdier-des-elections-en-rdc.pdf

Council of the EU, (2017), Council conclusions on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Press Release, March 6th, 2017,

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/03/06/conclusions-congo/

Crisis Group, (2017), Open letter to UN Secretary-General on Peacekeeping in the DRC, 27 July, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-congo/open-letter-un-secretary-general-peacekeeping-drc

Fischer F., Lundgren C.J., Jahjah S., (2013), Making Monetary Policy more Effective: The Case of the DR Congo, IMF Working Paper n°13/226, pp. 1-30, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13226.pdf

Gnassou L. (2017), The End of the Commodity Super-Cycle and its Implications for the DR Congo in Crisis, Harvard Africa Policy Journal, volume XII, Spring, pp. 77-88.

Gnassou L. (2017), Financing Sustainable Development in Fragile States: The Case of the DR Congo, The Development Study Association (DSA) 2017 Conference, September 6th, 2017, Bradford, The UK.

Gnassou L. (2017), Rising Chinese Overseas Assets in the Copper-Cobalt Belt of the DR Congo facing Political Instability, the International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas (ISSCO) Conference from November 17th to 19th, 2017, Nagasaki, Japan.

IMF, (2017), Letter of Mrs. C. Lagarde to Prime Minister Tshibala of the DR Congo, June 29th

IMF (2017), The Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, Restarting the Growth Engine, April, pp. 1-111,

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2017/05/03/sreo0517

IMF, (2016), IMF Staff Concludes Visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Press Release n° 16/268, June 8th, pp. 1-2,

https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16268

IMF (2013), The Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, Keeping the Pace, October, pp.1-116,

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2017/01/07/Regional-Economic-Outlook-October-2013-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Keeping-the-Pace-40866

Journal Officiel, (2002), Loi n°005/2002 du 07 mai 2002 relative à la constitution, à l’organisation et au fonctionnement de la Banque Centrale du Congo, pp. 1-17, http://www.leganet.cd/Legislation/Droit%20economique/Droit%20bancaire/article.banque%20centrale.pdf

Kamba-Kibatshi M., (2015), Impact of Monetary Policy of the Central Bank on the Inflation Rate in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Instruments, Implementation and Results, Nierówności społeczne a wzrost gospodarczy, n°42, pp. 462-481, http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-34398c2e-b5d2-42bf-8d11-dba398a63e2f

Masangu J-C., (2008), La République Démocratique du Congo face à la crise financière internationale, 4 novembre, Banque Centrale du Congo.

Ministère du Budget de la RD Congo, (2016), La loi de finances rectificative de l’exercice 2016, mai, pp.1-31, http://www.budget.gouv.cd/2012/budget2016/loi_finances_rectificative_2016.pdf

Mabi Mulumba E., (2011), Congo-Zaϊre: Les coulisses du pouvoir sous Mobutu, Témoignage d’un ancien Premier Ministre, Les Editions de l’Université de Liège, pp. 1-454.

Nachega J.C., (2005), Fiscal Dominance and Inflation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, IMF working paper, n°05/221, November, pp. 1- 42, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2003/wp03105.pdf

[i]: In 2015, Katanga was divided into the following provinces: Haut-Lomami, Haut-Katanga, Tanganyika, and Lualaba.

[ii]: On September 17th, 2007, the DR Congo and a consortium of Chinese private companies (China Railway Engineering Company (CREC), SinoHydro Corporation, and Zhejiang Huayou Colbalt Co. Ltd) signed a deal for USD 9.5 million, covering the infrastructure and mining sectors. The IMF criticized the Sino-Congolese agreement due to the government-guaranteed infrastructure financing, which could increase the country’s external debt burden over the medium term. In October 2009, the deal was revised. It was reduced to USD 6 billion to be compatible with debt sustainability.

[iii]: Gnassou L. (2017), Rising Chinese Overseas Assets in the Copper-Cobalt Belt of the DR Congo facing Political Instability, the International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas (ISSCO) Conference from November 17th to 19th, 2017, Nagasaki, Japan.

[iv]: As of December 2012, the review of the 2002 mining code started with donors’ assistance. In March 2015, the draft of the mining law was submitted to the Parliament. However, the commodities slump suspended the examination process. In May 2017, a revised draft of the mining law was submitted to the Parliament. Discussions on the draft mining law are likely to resume during the parliamentary session in September-October 2017.

[v]: This also includes improving the management of state assets through an efficient Public Sector Enterprises (PSEs) reform.

[vi]: Masangu J-C., (2008), La République Démocratique du Congo face à la crise financière internationale, 4 novembre, Banque Centrale du Congo.

[vii]: IMF, (2016), IMF Staff Concludes Visits to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Press Release, n°. 16/268, June 8th, pp. 1-2.

[viii]: Gnassou L. (2017), The End of the Commodity Super-Cycle and its Implications for the DR Congo in Crisis, Harvard Africa Policy Journal, volume XII, Spring, pp. 77-88.

[ix]: Beaugrand P. (1997), Zaïre Hyperinflation, IMF Working Paper n° 97/50, April 1st, pp. 1-39.

[x]: In July 2017, trade-unionists civil servants called for strikes in the country denouncing their purchasing power’s erosion. On July 20th, 2017, Prime Minister Tshibala agreed to increase civil servants’ wages following the council of ministers’ approval. Although such agreement will decrease social tensions, it will put additional pressure on public finance. It is worth noting that some strikes occurred, particularly at Kinshasa’s university. Other civil servants, including teachers, went on strike on September 4th, 2017.

[xi]: In June 2017, enterprises paid fiscal taxes in Congolese franc, which also contributed to the appreciation of this currency.

[xii]: Journal Officiel, (2002), Loi n°005/2002 du 07 mai 2002 relative à la constitution, à l’organisation et au fonctionnement de la Banque Centrale du Congo, pp. 1-17.

[xiii]: Fischer F., Lundgren C.J., Jahjah S., (2013), Making Monetary Policy more Effective: The Case of the DR Congo, IMF Working Paper n°13/226, pp. 1-30.

[xiv]: Beaugrand P., (2003), Overshooting and Dollarization in the Democratic Republic of Congo, IMF Working Paper n°03/105, pp. 1-27.

[xv]: Banque Mondiale, (2015), Rapport de Suivi de la Situation Economique et Financière de 2015, septembre, pp. 1-57.

[xvi]: Ministère du Budget de la RD Congo, (2016), La loi de finances rectificative de l’exercice 2016, mai, pp.1-31.

[xvii]: Banque Centrale du Congo, (2017), Communiqué, Comité de Politique Monétaire, 4 août, pp. 1-3.

[xviii]: Nachega J.C., (2005), Fiscal Dominance and Inflation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, IMF working paper, n°05/221, November, pp. 1- 42.

[xix] : Mabi Mulumba E., (2011), Congo-Zaϊre: Les coulisses du pouvoir sous Mobutu, Témoignage d’un ancien Premier Ministre, Les Editions de l’Université de Liège, pp. 1-454.

[xx]: The late promulgation of the State budget has affected the preparation of the presidential elections.

[xxi]: Since 2017, the pressure has been increased for extractive companies, which do not create favorable environments for private sector development. From August 29th to 30th, 2017, the transitional government organize a conference in view of improving the country’s legal framework for investors.

[xxii]: Gnassou L. (2017), Financing Sustainable Development in Fragile States: The Case of the DR Congo, The Development Study Association (DSA) 2017 Conference, September 6th, 2017, Bradford, The UK.

[xxiii]: In 2008, the IMF and the DRC started discussions on an economic program, known as PEG II, covering 2009-2011. On December 11th, 2009, the IMF board approved the three-year arrangement of USD 551.45 million for the DR Congo under Extended Credit Facility (ECF) program.

[xxiv]: IMF, (2017), Letter of Mrs. C. Lagarde to Prime Minister Tshibala of the DR Congo, June 29th.

[xxv]: From December 30th, 2008 to February 27th, 2009, the central bank’s gross international reserves decreased from USD 77 million to USD 32.87 million. The country was virtually bankrupt. On March 12th, 2009, the IMF provided USD 195 million under the Exogenous Shocks Facility (ESF), As a result, the central bank’s international reserve rose from USD 237.29 million to USD 894 million from March 31st to September 30th, 2009. In February 2009, the World Bank provided a USD 100 million emergency loan to soften the impact of the global recession.

[xxvi]: Kamba-Kibatshi M., (2015), Impact of Monetary Policy of the Central Bank on the Inflation Rate in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Instruments, Implementation and Results, Nierówności społeczne a wzrost gospodarczy, n°42, pp. 462-481.

[xxvii]: The DR Congo has experienced several political transitions, including at the end of the second republic under the Mobutu regime. See Mabi Mulumba E., (2011), Congo-Zaϊre: Les coulisses du pouvoir sous Mobutu, Témoignage d’un ancien Premier Ministre, Les Editions de l’Université de Liège, pp. 1-454.

[xxviii]: Council of the EU, (2017), Council conclusions on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Press Release, March 6th, 2017

[xxix]: CENI, (2017), Calendrier électoral : Décision n°065/CENI/BUR/17 du 05 Novembre portant publication des élections présidentielles, législatives, provinciales, urbaines, municipales et locales.

[xxx]: Crisis Group, (2016), Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The “Street” and Politics in DR Congo, Briefing 123, 13 October 2016.