In September 2018, the Indian Supreme Court made history by unanimously voting to repeal Section 377, which explicitly forbade “unnatural offences of carnal intercourse” and was often used against the country’s LGBT+ community. As the ruling was being celebrated in India, three separate challenges were made in Singapore’s courts against the country’s similar Section 377A. All three challenges were shot down, with the presiding judges concluding that, although not actively enforced, 377A “serves the purpose of … showing societal moral disapproval of male homosexual acts.”[i]

Despite the differences between Singapore and India in demographics and culture, their legal systems are both derived from the British-era Indian Penal Code, including the basis of Sections 377 and 377A. Also, roughly the same percentage of Singaporean and Indian people surveyed on the issue support same-sex relations.[ii] Thus, it is imperative to explore the factors which led to the repeal of India’s Section 377 and retention of Singapore’s 377A as well as the lessons that Singaporean policymakers can draw from the Indian experience by comparing the current challenges faced by the LGBT+ community in Singapore and India after Section 377’s repeal.

Constitutional and Media Factors

High courts in Singapore and India have traditionally taken divergent approaches in how they see their role in upholding their respective country’s constitution. Historically, India’s Supreme Court has a history of judicial activism on constitutional adjudications and has been globally recognised for its “activist” rulings in areas such as the right to life, health, and education.[iii] Specifically, Indian high courts often invoke the principle of “constitutional morality,” which promotes “the State to maintain such a heterogenous fibre in the society … [despite] popular sentiment prevalent at a particular point in time.”[iv]

In contrast, Singapore’s judiciary reflects the values of Singaporean society, in which there have always been tensions between its communitarian “Asian” values, which emphasizes the nuclear family as the “fundamental building block” of society over “alternative lifestyles,”[v] and its image of a global cosmopolitan hub. Policymakers justified Section 377A as a means to appease its conservative majority while not actively enforcing it in order to maintain its reputation as an attractive hub for foreign talent. In practice, Singapore’s judiciary serves to maintain the status quo vis-à-vis the constitution while the constitutional role of India’s courts has allowed it to pass rulings that are more progressive than the society they represent.

Additionally, differences in legislation regarding news and popular media in India and Singapore have resulted in India having a more welcoming environment for LGBT+ representation. Indian media is considerably less restricted than its Singaporean counterpart, which is heavily regulated by the Infocomm Media Development Authority. Despite the government claiming a neutral stance, queer politics are consistently framed as a threat to Singapore’s communitarian stability while positive queer representation is either severely limited or banned.[vi] In both countries, the advent of streaming services and social media have allowed easier access to media with positive LGBT+ representation and allowed LGBT+ activists a bigger platform to spread their message and challenge entrenched societal norms.

After Repeal

Numerous challenges remain for India’s LGBT+ community. The repeal of Section 377 just decriminalised sex acts; LGBT+ people in India still face similar challenges as their counterparts in Singapore, such as discrimination in the workplace, harassment in the public and private sphere, and legal obstacles to getting same-sex relationships recognised. This is particularly true in the more conservative regions of India, where some LGBT+ people have even experienced an uptick in harassment.

However, the repeal of Section 377 signals an evolution in the LGBT+ rights discourse in India, as advocates recognise that this is the first step towards more robust civil rights for the country’s sexual minorities. Since the mere act of being LGBT+ is no longer criminalised, LGBT+ people can now seek direct legal protection from the courts. The ruling also had positive effects on the internal and external perceptions of the LGBT+ community in India as significantly fewer LGBT+ individuals feel the need to remain anonymous or silent about their sexuality or gender orientation. This paradigm shift can also be seen in Indian mainstream media, where there has been an increased presence of LGBT+ role models and representation.

Lessons for Singapore

Despite its societal and legal differences from India, there are still some lessons that Singapore can draw from India’s experience with Section 377. It is unlikely that the People’s Action Party (PAP) in Singapore, which has consistently claimed a neutral stance on LGBT+ rights in Singapore, will repeal Section 377A without a significant popular mandate. There is also a fear that moving too fast in repealing Section 377A may exacerbate homophobic sentiment in Singapore, which is a valid concern given the increase in anti-LGBT+ vitriol during the height of Singapore’s Section 377A debate in 2018.[vii] In this context, the question should be how to make Singaporean society more accepting of its LGBT+ population given the absence of any concerted top-down effort to repeal Section 377A.

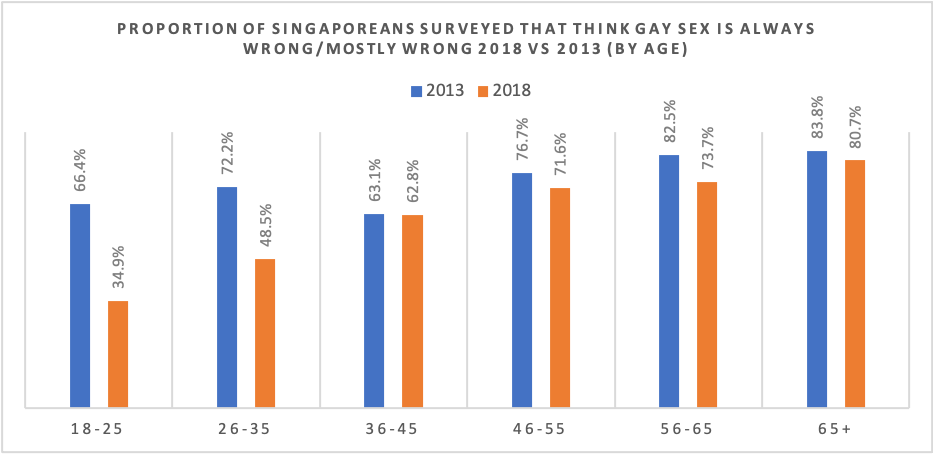

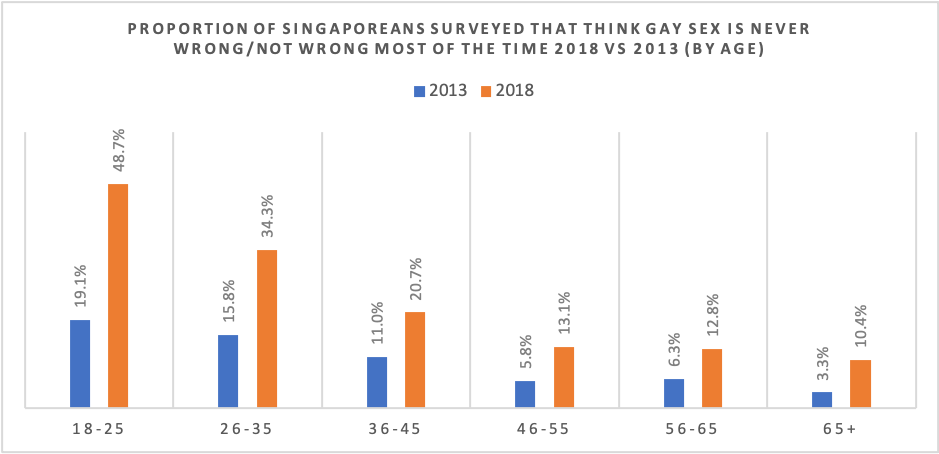

Fortunately, Singaporean attitudes towards LGBT+ people are becoming more accepting. According to surveys conducted by Singapore’s Institute for Policy Studies conducted in 2013 and 2018, the proportion of Singaporeans who believe that gay sex is always or mostly wrong decreased from 80% to 63.4%, while those who believe that it is not wrong at all or most of the time more than doubled from 10.3% to 21.6% over this period.[viii] Given that this change is mostly driven by younger Singaporeans, it is likely that the PAP may eventually be forced to yield its position on Section 377A in a generation or two.

Source: Institute of Policy Studies

Source: Institute of Policy Studies

While the repeal of Section 377A is arguably inevitable, there are also several things that the Singaporean government can do to steer public sentiment towards it. Singaporean policymakers need to re-examine their supposedly “in-the-middle” stance on LGBT+ issues, which continues to marginalise its LGBT+ minority in favour of its conservative majority.

Positive representation and advocacy in the media was instrumental in steering Indian public opinion towards supporting the repeal of Section 377.[ix] In this regard, there are certain things that the Singaporean government can quietly do to sway public opinion towards accepting LGBT+ Singaporeans.

Singapore could afford to weaken its censorship and ratings of popular media. Currently, Netflix shows directed at young adults in Singapore with even the slightest queer representation are given an M18 rating in Singapore.[x] Weakening such provisions will go a long way towards normalising queer people, which will undermine current prejudices.

Pro-LGBT+ Singaporean advocacy groups face legal obstacles in getting officially registered, often being rejected due to vaguely defined legal clauses that forbid the creation of groups that are prejudicial to the public order or welfare of Singaporean society.[xi] If the government truly wants to claim its neutral stance on queer issues, it could afford either making this process more transparent or easing these ambiguous restraints on LGBT+ organisations.

Such actions can be quietly introduced and would allow policymakers to test the waters of repealing Section 377A while also creating a more even playing field for LGBT+ activists and voices. With younger Singaporeans becoming increasingly accepting of their country’s LGBT+ population, Section 377A’s repeal is inevitable, but it is up to the PAP if it wants to resist this or not.

This submission is an executive summary of the author’s original research paper, which can be found here.

Endnotes:

[i] Channel News Asia, “High Court Judge Dismisses All Three Challenges to Section 377A.” Accessed 1 May 2020. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/377a-challenge-dismissed-high-court-judge-penal-code-12588738.

[ii] Rampal, Nikhil, “Section 377 Anniversary: Half of Country Still Doesn’t Approve of Same-Sex Relationships,” India Today, 6 September 2019. https://www.indiatoday.in/diu/story/section-377-anniversary-same-sex-relationships-1596408-2019-09-06; Institute of Policy Studies, “IPS Working Paper No. 34 – Religion, Morality and Conservatism in Singapore,” Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, 2 May 2019. https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/ips/news/details/ips-working-paper-no.-34-religion-morality-and-conservatism-in-singapore?fbrefresh=637406412225573401.

[iii] Kapur, Manav, “Constitutions, Gay Rights, and Asian Cultures: A Comparison of Singapore, India and Nepal’s Experiences with Sodomy Laws Articles and Essays,” Indian Journal of Constitutional Law 6 (2013): 117–75.

[iv] Supreme Court of India, “Full Text of Supreme Court’s Verdict on Section 377 on September 6, 2018,” The Hindu, 6 September 2018, sec. Resources. https://www.thehindu.com/news/resources/full-text-of-supreme-courts-verdict-on-section-377-on-september-6-2018/article24880713.ece.

[v] National Archives of Singapore, “Shared Values,” 1991.

[vi] Obendorf, Simon, “Both Contagion and Cure: Queer Politics in the Global City-State.” In Queer Singapore, edited by Audrey Yue and Jun Zubillaga-Pow, 97–114. Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures. Hong Kong University Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1xcs1v.11.

[vii] South China Morning Post, “Why Some Members of Singapore’s LGBT Community Prefer Life in the Shadows,” 6 February 2019. https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2185099/why-some-members-singapores-lgbt-community-prefer-life.

[viii] Institute of Policy Studies, “IPS Working Paper No. 34 – Religion, Morality and Conservatism in Singapore.”

[ix] Aboy, Silvia Puerto, “INDIA: When Justice Is on Your Side, You Have to Keep on Fighting,” CIVICUS. Accessed 8 May 2020. https://www.civicus.org/index.php/media-resources/news/interviews/3683-india-when-justice-is-on-your-side-you-have-to-keep-on-fighting.

[x] These shows include The Dragon Prince, Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts, and She-ra and the Princesses of Power.

[xi] ILGA, “State-Sponsored Homophobia Report,” 14 September 2017. https://ilga.org/state-sponsored-homophobia-report.

—-

Image credit: The Online Citizen