In one of India’s most far-reaching decisions since it gained independence, Prime Minister Modi suddenly announced on November 8th that the country would be withdrawing the legal status of its 500 and 1000 rupee notes. Equivalent to about USD $7.40 and USD $14.70 respectively, these two bills alone comprise over 80% of the currency in circulation. Immediately following the announcement, cash withdrawals from banks were limited to 20,000 rupees (USD $295) per week to serve liquidity needs, old currency of value up of only to 4000 rupees (USD $59) per person per day could be exchanged for new currency over the counter at banks, and citizens would be permitted to deposit any amount of old banknotes to their accounts through December 30, 2016.

Importantly, the source of the bank deposits must be disclosed and the total amount is subject to tax. The now-debunked notes are being replaced with 2000 rupee notes in addition to new 500 rupee notes that are more resistant to counterfeit. In a largely cash-driven economy where everything from restaurant bills to new pieces of property are often paid for in cash, the policy of demonetization was motivated by the PM’s desire to curb corruption, eliminate black money and counterfeit notes, and pause funding for illicit activities such as terrorism or espionage.

Although implemented with admirable intentions, this policy is somewhat overzealous and not greatly beneficial on its own. Given that it has been enacted, however, Modi’s administration can use the current period of change and uncertainty to carry out some successful follow-up reforms.

Near-term Outcomes vs. Long-term Objectives

Immediately after the policy was implemented, an increase in bank deposits of old currency coupled with a decrease in the supply of new currency resulted in a substantial impact to consumption and productivity. As many individuals found themselves waiting in bank lines for hours, they were suddenly beleaguered with lack of liquidity, wasted time, and other administrative burdens.

Projections as to how the new policy will affect GDP vary. However most estimates project that GDP growth of India, one of the fastest growing economies, will slow by between one and six percent for the next couple of quarters. There has also been speculation that longer-run GPD measures may be adversely affected. One hope, however, is that these substantial costs will be offset by benefits such as the curbing of illegal activity and increase tax revenue. One amendment to India’s Income Tax Act that was proposed as a complementary policy, for example, proposes a minimum 50% tax on bank deposits of old currency which are unexplained (and a harsher 90% tax on deposits that are not voluntarily reported). This policy would serve as a major penalty to those who gained money through illegal means.

There are other projected outcomes of demonetization that will likely be beneficial as well: interest rates may decrease as money is transferred from the public’s hand to banks (making it cheaper to borrow, which will encourage spending and investment), the budget deficit may decrease (a result of the fact that the government is able to collect more taxes), inflation may decrease (a policy objective that India has maintained), and the country will become more receptive to fintech (the financial technology sector) as its dependency on paper-cash is decentivized. The extent to which any of these benefits are realized is entirely dependent on the government’s post-demonetization actions.

Campaign Finance and Political Disruption

While the economic effects of demonetization are understandably considered first, this policy has significant non-economic implications as well. Within politics, for example, contested and critical elections will soon be hosted in the two Indian states of Punjab and Uttar Pradesh. Demonization is incredibly consequential to campaign financing in these regions as three-fourths of party funds come from undocumented sources. Parties often use this unreported money- especially smaller denomination bills- to bribe voters in advance of the election. By taking away black money, this policy therefore provides an unexpected impediment to the illegitimate activities of all parties.

Interestingly, some citizens believe that the timing was politically motivated as they suggest that Modi’s BJP party is better equipped to overcome the issue than other parties. In a State such as Uttar Pradesh, for example, campaign financing data indicates that the BJP party is far less cash-dependent than its rivals, which means that this move might help the BJP party gain advantage in parliament’s upper house. Whether or not this is the case, it is definitely true that all parties will have to adapt to strategies that are less centered around illicit cash and bribery in this election.

Experiencing the Bad and Hoping for the Good

Although this policy of demonetization has found some support, it has also been met with heavy criticism. To begin with, one extremely valid concern relates to the credibility of the Indian government and the standing of its fiat money. In a personal interview, Professor Akash Deep, a Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School who specializes in financial markets, offered a very insightful analysis of this irony:

The government, in one stroke, has said that 86% of the money they were standing behind yesterday they are no longer standing behind today, and that is a very risky thing to do. It seems strange that government is undermining faith in its own authority by demonetizing money that it had issued itself. Beyond the immediate costs, that [credibility loss] is a major long-term cost. While I don’t disagree that the black money problem is huge, I think that debilitating the whole payment system in this manner is not at all the right tool to use. Demonetization is at immense cost to people and immense cost to the trust that underpins the fiat-based currency system.

In addition to the government’s reputational costs, Indian citizens continue to endure a great deal of inconvenience and uncertainty. While some point to the long lines and administrative burdens as indicative of a poorly planned policy, others argue that the policy will not achieve its objectives in the end. Natasha Sarin and Lawrence Summers of Harvard University, for example, raise concerns of “equity and efficacy” through their statement that “those with the largest amount of ill-gotten gain do not hold their wealth in cash but instead have long since converted it into foreign exchange, gold, bitcoin or some other store of value… Corruption will continue albeit with slightly different arrangements.” In other words, they argue that much of the black money has already been converted into non-cash assets.

After visiting India in the midst of this new policy and speaking with a number of individuals about the short- and long-run effects, I conclude that this policy comes at great cost to the government and the people it should be serving. The government should have brainstormed alternative ways to target the problem of corruption and black money. Now that the policy has been put in place, however, the government can still serve its people by implementing a number of follow-up reforms that can enhance the goal of broader and more inclusive growth.

One specific area of progress that this policy can enhance, for example, relates to digital transactions and fintech. Modi is encouraging individuals to use their mobile phones for their financial transactions in order to facilitate transparency and convenient payment transfers, and demonetization has already acted as a strong impetus, as explained by one Bloomberg commentator:

[This policy] could end up being the best thing to happen to its nascent online finance industry and haul its antiquated economy into the 21st century by making digital payments mainstream… While the situation’s still developing, India could end up a rare bright spot for financial technology investors.

Harvard Kennedy School Lecturer in Public Policy, Professor Martha Chen, qualifies this point in an interview by stating that “financial inclusion has already been a revolution in the making and there has already been serious work on the ground. It would be all the better if this policy happens to accelerate the progress, but it wouldn’t be starting the revolution.” This point supports the fact that demonization is potentially valuable as a policy that supports a set of new reforms.

Given that the policy’s downsides have been set in place, it is now the Indian government’s responsibility to follow up demonetization with strong economic, social, and political policies such as ones that target tax compliance, campaign financing, and financial inclusion. Modi can still use this policy to benefit the country if he is purposeful and strong with follow-up reforms.

___

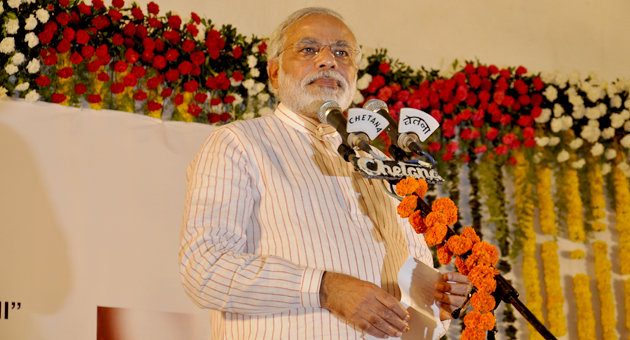

Photo Credit: Flickr via Creative Commons