Fighting Corruption in India

By Sujoyini Mandal, Opinions Columnist, MPP ‘13

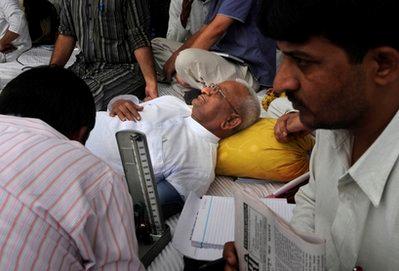

For the very first time, India has witnessed an outburst of citizen protests chiefly via social media, including Facebook and Twitter. Anti corruption campaigns led by the hunger strike of social activist Anna Hazare have captured the Indian imagination within and outside the nation’s borders in the past few months. Riding on a popularity surge, ‘Anna’ seeks the triumph of people power and to override Indian democratic institutions.

Days into his hunger strike, this hitherto unknown social activist became an overnight media sensation. His charm offensive is similar to that of Gandhi, who successfully used non-violence as an agent for peaceful reform during the heady years of the Indian independence movement. Half a century later, Anna wants to replicate the same principle. Not everyone, however, buys into his philosophy.

As Suhit Sen of The Guardian righty points out, Anna’s appeal is restricted to the middle classes and capitalist entrepreneurs—hardly a recipe for an inclusive political reform movement.

Secondly, while his means may be Gandhian, Anna Hazare’s demands are certainly not. Contrary to Gandhi’s ideas about the decentralization of power, as social commentator Arundhuti Roy explains, the Jana Lokpal Bill (or the citizen ombudsman bill) is, contrary to popular belief, an anti-corruption law in which a chosen set of representatives, headed by Anna, will “administer a giant bureaucracy … with the power to police everyone from the Prime Minister … to the lowest level of government.”

The controversial law would give Anna powers of investigations, prosecution and surveillance. In essence, it serves to create an independent administration, a watchdog over every government component, including the judiciary. Two oligarchies instead of one.

The secondary consequences of Anna’s hunger strike are of no less consequence. Taking advantage of ‘brand Anna’ and the resultant mobilization of the middle and upper classes that are the primary supporters of the movement, political parties have jumped on the bandwagon. LK Advani from the opposing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has decided to go on a “rath yatra” to support Anna, while the Gujarat Chief Minister has initiated a similar hunger strike to join the mass anti-corruption voice against the ruling Congress Party. While free riding to gain airtime and political mileage is nothing new in Indian politics, this event is particularly significant in the amount of international attention and press it has garnered.

With the Indian government ceding to Anna’s initial demands to initiate the process of creating the bill, the role of the judiciary and the justice system are now in question. Is the Anna movement constitutional, such that the judiciary would be acting against the Indian people if they struck it down?

If the judicial review process does strike down the bill, the consequences would be far reaching for the Indian constitutional democracy. Pro-democracy activists will likely fight for free speech and liberty, claiming that the process is a dangerous liability to democracy relying on outmoded concepts of human rights that disenfranchise common citizens. Constitutionalists, on the other hand are expected to favor the powers that be and to point to the system of checks and balances built into the Indian democratic institution.

The answer will be played out in the next few months as India debates who should be framing the bill. For now, the largest democracy in the world continues to look for innovative ways to fight endemic corruption.